Crowdsourcing data projects help faith congregations get involved in creating justice

Volunteering for research initiatives like the Mapping Prejudice project in Minneapolis educates church members on how to rectify present injustice.

As the Rev. Lisa Friedman of the Unitarian Universalist Church of Minnetonka observes, few people wake up in the morning saying, “I want to read property deeds.”

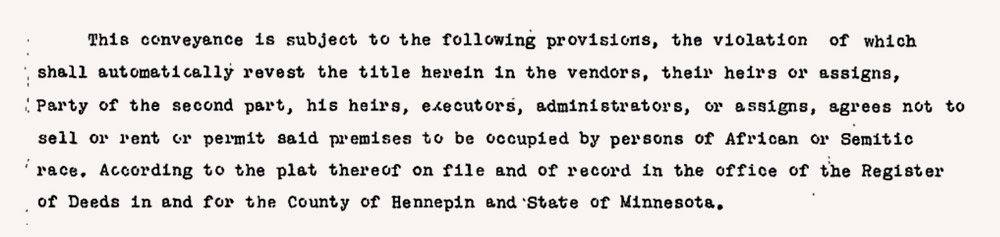

But members of the Minnesota congregation have done just that, going online to join thousands of other volunteers in transcribing racially restrictive covenants from historic property records. These restrictions, prevalent in the first half of the last century, kept people who weren’t white from buying or occupying certain property.

Friedman’s congregants are far from alone in seeing both the reward and the responsibility of joining in uncovering data that continues to have an impact in the present day. Faith communities across America have found opportunities to offer their help to such projects — and have learned about their own history and locations in the process.

In joining the massive crowdsourcing data effort known as the Mapping Prejudice project, UUCM church members were helping expose the racist practice of land covenants, which drove segregation in Minneapolis, neighboring suburbs and many other U.S. cities. Such housing policies created the foundation for racial disparities in education levels, employment, poverty rates and homeownership across the country, with some of the largest gaps persisting to the present-day Minneapolis-St. Paul metro area. The U.S. Supreme Court held in 1948 that such covenants were unenforceable, yet it wasn’t until 1968 that the federal Fair Housing Act made them explicitly illegal.

“We went through a process of learning as a congregation as part of our commitment to racial justice and looking at what it means to repair past harm and how housing impacts so many other things, housing and other inequities,” Friedman said. “That learning has rippled out to the neighborhood, to the city and to a larger story. … If we want to be an inclusive, justice-oriented community, it is really important for us to take a stand and raise this awareness.”

What projects in your city help uncover community history?

The participation of the Unitarian Universalist Church of Minnetonka in the Mapping Prejudice project is just one example of how churches and their members can contribute to developing data and learning from it. The process can help members and congregations understand their history, manage programs and services to meet changing needs, and take part in or learn from surveys about how their cohorts are responding to the pandemic and other issues.

Faith organizations were some of the first to step up to join Mapping Prejudice, according to the project’s co-founder and director Kirsten Delegard. Research she found shows that one way to change people’s thinking and introduce new concepts is to do so in a place where they feel safe and have trusted relationships with other people.

“There’s already a framework [in faith communities] for understanding moral responsibility,” Delegard said. “There’s an engagement — ‘What is my role in the world? How can I make the world a better place through my action?’ People are joining a faith community often because they want to put their faith in action. This provides a really good vehicle for that.”

Researching local parish deeds for restrictive covenants will be among the subjects of a new online course the United Methodist Church is to begin offering in September, according to Ashley Boggan Dreff, the general secretary of the General Commission on Archives and History for the church.

The Local Church Historian School course will be self-driven over 14 to 15 weeks and will include video and interactive assignments from leading Methodist scholars and archivists on additional subjects such as determining which documents to save and how to archive them, Dreff said.

Are there experts around you who could help you research your context?

Dreff hopes the new, online format, with opportunities for participants to comment and join in community, will get more members to register for and complete the course. When the church originally offered the course through email in 2020, some 117 graduated of the more than 700 who signed up. The overarching goal is to encourage members to research church history, learning how Methodism has shaped their church and how local congregational history has shaped the Methodist movement.

“It’s a way to rebuild community of a local church, to establish yourself not only as a congregation but how your congregation relates to its surrounding community,” Dreff said. “What have you historically done to benefit or better the community around you? [And it’s important to] explore some of the darker moments in one’s past. How has the congregation not stood up for justice or been actively doing harm to those around it? There’s a lot of potential in digging this out, both in terms of honoring your past and reconciling the past.”

What are some primarily online activities that you could encourage your community to take part in?

When a church owns property with a restrictive covenant, members taking this course could see how the demographics of the community may have shifted from that time to the present, Dreff said. Members also could look into why their church changed locations — whether, for instance, it received the new property as a gift or whether “white flight” lay behind the move.

A supplemental course may focus on the District of Columbia, where in at least three instances, contemporary United Methodist churches with predominantly white or Black congregations are within half a mile of each other, Dreff said. At some point in history, Black members walked out of the white churches, bought their own property and established new, separate congregations.

“What is their contemporary relationship?” Dreff said. “Have they discussed their historical relationship? Has there been any attempt at reconciliation?”

In Milwaukee, several congregations of multiple faiths are eager to identify and find ways to discharge racial covenants in that city, according to Anne Bonds, an associate professor of geography at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee.

Members likely will begin transcribing deeds this summer as part of the university’s Mapping Racism and Resistance in Milwaukee County project, said Bonds, a leader of the project, which is working in collaboration with the Mapping Prejudice project in Minnesota.

Also interested in taking part are two nearby Catholic parishes, one in a wealthier, predominantly white area, the other in a Black neighborhood.

“They’ve been trying to come to terms with the differences in their parishes in terms of the racial makeup — how they’re so close together yet there’s this deep divide racially and also socioeconomically,” Bonds said. “They’re wanting to know more about the history of segregation in their community and in their neighborhood, and how it happened.”

A sense of urgency is driving interest in the project for many congregants.

“There’s a recognition of the way in which these communities that are predominantly white have really benefited from these policies of racial exclusion,” Bonds said. “Part of it is facing that history, and also a desire to act in faith to address what are seen as moral wrongs that have persisted. The desire and the goal to act on this and use this data is to both understand the history of the communities and to face that history but also to make change.”

Garlinda Burton, the director of resource development for the General Commission on Religion and Race of the United Methodist Church, devoted an episode of the commission’s podcast series to the Mapping Prejudice project, hoping to raise awareness to encourage other congregations to pursue similar data-driven efforts. Burton spoke to Delegard, Friedman and Daniel Pierce Bergin, the producer-director of a Twin Cities PBS documentary about the project, “Jim Crow of the North.”

“The thing that we hoped to convey was that institutional and systemic racism is real,” Burton said. “That it is having an impact in this very moment on how not only governments operate but how the church operates, how churches are funded, disparities in class, economics and race, education and resourcing — in this country and around the world. And these are the things that Jesus concerned himself with on his earthly walk.”

Examining deeds for racial covenants helps expose institutional racism that otherwise can stay hidden, Burton said.

“The message was, ‘Where can you start to repair? Where can you start to learn?’” she said of the podcast. “Everyone likes to talk about racial reconciliation. Everybody wants to reconcile, but nobody wants to do the work of repair that is needed for real reconciliation to happen. … Where can we start as a church to undo the things that are not of Christ, that keep us segregated and keep people broken and at war?”

The issues related to racially restrictive covenants hit home for the Unitarian Universalist Church of Minnetonka more than a decade ago when it discovered a covenant on the property it was buying for a new church. The May 2020 police killing of George Floyd, Friedman said, added urgency to the church’s commitment to social and racial justice work.

But no clear path for what to do about the covenant appeared until they learned of the Mapping Prejudice project. Beginning in late 2020, several of the church’s 300-plus members completed training and began transcribing digitized deeds on an online “people-powered research” platform known as Zooniverse.

Mapping Prejudice revealed that racial covenants were in place throughout the neighborhood of its new church as well as another neighborhood in Wayzata, the small city on the shores of Lake Minnetonka where the church, with more than 300 members today, has served western Minneapolis and its suburbs for some 60 years.

How have you attempted to understand the divisions of race, economics and class in your location?

The congregation had the covenant removed from its property title in February 2021, Friedman said. The church worked with Just Deeds, which provides free legal and title services, under a state law that allows property owners to remove discriminatory language from property titles. The city notified residents of the Wayzata neighborhoods with racially restrictive covenants that it could connect them with Just Deeds to explore their deeds’ histories.

The covenant’s removal coincided with the church’s decision to place a Black Lives Matter banner on the front of its new building, visible to motorists on a busy nearby highway.

“Part of the conversation was that we’re not just putting a banner to have a banner. We need to be doing the work to make that statement real,” Friedman said.

Are there actions you could take, symbolic or otherwise, that acknowledge the history of the places you serve?

Questions to consider

- What projects are in your community that are helping uncover your community’s history?

- Are there experts around you who could help you research your context?

- What are some primarily online activities that you could encourage your community to take part in?

- How have you attempted to understand the divisions of race, economics and class in your location?

- Are there actions you could take, symbolic or otherwise, that acknowledge the history of the places you serve?

Share