February 9, 2021

Jennifer Harvey: Dismantling racism requires knowing our history

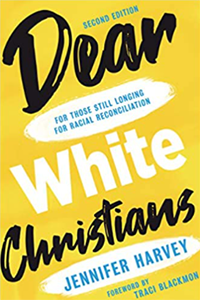

Photo courtesy of Jennifer Harvey

In the second edition of her book, the author of “Dear White Christians” reiterates that listening and responding to calls for reparations precedes the possibility of reconciliation.

When Jennifer Harvey wrote her book “Dear White Christians: For Those Still Longing for Racial Reconciliation,” she couldn’t have imagined the context in which it would be published.

Just weeks before the book came out in 2014, Michael Brown was killed in Ferguson, Missouri, and a powerful advocacy movement burst onto the national scene with a simple message: Black Lives Matter.

In the wake of the protests, some white churches were confused, even shocked, at the “grief-filled rage” shown in Ferguson, Harvey said.

And some of those churches turned to Harvey and her book for education.

“The book is for white Christians … who are asking the questions, ‘Why are our churches built so white? Why don’t we have more multiracial communities? Why do we seem so divided and alienated still?’” she said.

“The book is for white Christians … who are asking the questions, ‘Why are our churches built so white? Why don’t we have more multiracial communities? Why do we seem so divided and alienated still?’” she said.

Her book, the second edition of which was released last summer, helps white Christians understand how the history of Black Power movements informs current organizing efforts and calls to redistribute resources.

Understanding and heeding this history, she says, is a prerequisite to moving toward the Christian vision of reconciliation.

Harvey is a professor of religion at Drake University and an award-winning author and public speaker. She is also the author of “Raising White Kids: Bringing Up Children in a Racially Unjust America.”

Harvey spoke with Faith & Leadership’s Chris Karnadi about the importance of knowing the history of Black Power movements and the differences between the paradigms of reconciliation and reparations. The following is an edited transcript.

Faith & Leadership: How important is it to know and teach history that doesn’t whitewash civil rights?

Jennifer Harvey: One of the things I excavate in the book is the degree to which Black Power movements are obscured in how we remember history. What I explore in the book is that these power movements were not only part of the civil rights movement but they also had Christian elements.

It’s critically important that we know these histories that many white communities, and in this case, white Christians, either haven’t been taught, have ignored or have been taught to ignore.

I was raised in the church. I’ve been a Christian my whole life. I didn’t learn any of these histories until I was doing my Ph.D. at Union Seminary. I had even gone through an M.Div. program without learning this history.

F&L: Can you describe the importance of Black Power movements?

JH: The history of power movements helps us reckon differently with what came out of the civil rights movement. It wasn’t wonderful progress where white Christians and Americans started doing better around Black demands for racial justice; white Christians started to reject and step back from civil rights when it made progress.

We have to learn this history, because Black Power movements made different kinds of demands from calls for integration. They demanded power and resource redistribution, and part of the crisis we’re in today is directly related to how deeply we have — not just white Christians but white America — ignored and rejected those calls for power and resource redistribution.

Knowing that history is important for that reason, because our actual racial story is not the story we often tell in the white church. So that’s one piece of the reason why it’s so important.

The other reason that it’s so important to excavate and remember these histories is that the erasure of those histories is itself a form of racial harm.

It’s not just an accident that we don’t know the history of Black Power movements inside the white church — the way James Forman and other activists, including Black clergy, for example, made calls for reparations to white communities in 1969.

It’s actually a site of sin, is how I would talk about it. We actively rejected the history of Black clergy in Black Power movements, and then we pretended those calls had never been made.

There’s been this kind of amnesia from white Christians; we don’t even know the sins that we’ve committed, and so we’re stuck in our calls for equity and reconciliation and diversity. These calls are so hollow, but we don’t even know that, because we haven’t named and confessed the erasure that we actively committed moving out of the civil rights movement era.

I say this in the book, but it’s critically important to see that many of the things Black Power advocates were naming and predicting about the reality of racial relationships is what we’re seeing right now. In the last five years, this beast we have never repented from or repaired has created our national climate. I feel very clear about that.

It’s past time to confess what we’ve done and pick up partnership with those communities who have never stopped making those same demands.

F&L: Were Black Power movements prophetic?

JH: I think “prophetic” is the right word to use. They were telling us that integration — or reconciliation, which is the way we talk about it in the church — was going to fail without massive resource redistribution.

To be clear, I long for reconciliation. I do think that’s the space to which we are called, but just making integration the solution to racial injustice and racial violence is misguided. You need to change the systems of exploitation.

Black Power movement leaders and the diverse communities that were organizing with them were calling for things like reparations to enable resource redistribution that would enable Black self-determination, Black business cooperatives, Black media networks and outlets.

They called for a radical transformation in how we thought about public education. If you have inequitable school systems, where Black children don’t have access to high quality education because of segregation and racial injustice, just integrating kids is not a solution. It’s important to reject segregation, but simply putting some Black children in a white classroom with a white teacher who doesn’t even know how to love Black children is not necessarily better.

You need Black teachers. You need Black principals. You need to shift all the power structure so that resources are distributed differently.

They also called for a radical rethink on policing. Police violence in the ’60s was creating these instances of just community rage and grief because of the way policing happened in Black communities, which is still very relevant today.

We cannot be siblings to one another in a genuine, mutual way if we haven’t repaired the harm and the exploitation that were not only present in the foundation of the United States but are actively constructed even today.

We need to repent and repair those things in order to even begin to talk meaningfully about beloved community. What I’m trying to get us to think about as white Christians in the book is that history had prophetic things to say to us about who we actually are and how we could be converted to become something different.

F&L: You make this delineation in the book between a reconciliation paradigm and a reparations paradigm. Can you explain both of those?

JH: The reason I use the word “paradigm” is because I think that helps us think about what kind of lens we are using. I believe as a Christian that reconciliation is a state to which we are called, but the framework of reconciliation is a problem, because of what it teaches us to be.

For example, a reconciliation paradigm is universal. It would say things like, “We need to come to the table and celebrate and embrace our differences. We need to come together across our diverse experiences and learn to love each other more fully and truly.”

The problem with reconciliation as a paradigm, again separate from actually being reconciled, is that it assumes that our differences are equally problematic. A reconciliation paradigm assumes that I as a white person need to better come to love Blackness, Nativeness and Latinoness and also implies that Black, Native and Latino people should better love my whiteness in order for all of us to reconcile. But it’s not a moral parallel. Blackness and whiteness are not moral or cultural or political parallels.

White people owe something different and distinct if we are going to be reconciled. So a reparations paradigm says that the crisis of racism and racial injustice is a multiracial crisis and we each have a different location in it.

In particular, it says historically white communities, whether actively or passively, have engaged in perpetrating harm. We have unjustly reaped economic benefits from that harm, and we’ve also been spiritually and morally malformed by our participation in that harm.

So if we want to be at a multiracial table, then we name that and repair that as the way we come to the table. There’s no responsibility of Black people learning to better appreciate and understand white people. It’s about, “How do we together address and redress the structures of harm, violence and unjust benefit that exist between us?”

If we can redress those and redistribute resources from white communities to communities of color, that actually might make us beloved to one another. But the repentance and the repair piece is how white folks show up to the table in a reparations paradigm.

F&L: You say that you’ve seen progress since 2014. Can you talk about ways in which you’ve seen white Christians moving forward and how some of the gaps remain?

JH: I tried to include in the book’s appendix some anecdotal examples of reparations-informed movements that have begun to emerge in the last four years. They’re scattered all over the place, but they’re worth naming, because it’s an energy and sort of responsive kind of percolation that is starting to happen.

The Minnesota Council of Churches is starting to unroll a 10-year project of reparations relative to Native communities in a central way, but there is also language for reparations toward African American communities.

The Fellowship of Reconciliation has a national reparations and truth telling campaign that has gotten underway. I’m seeing in my local community in Des Moines in the last year all kinds of white clergy who have — not just as individuals but speaking in the name of their church — have been not just putting signs for Black Lives Matter on their churches but have been out organizing with Black Lives Matter movement leaders.

They are organizing by asking, “OK, what do you need us to do? What role do you need us to play? How do you need us to hold the police authorities accountable?” That’s another example.

It’s just new for white communities. I think a lot of people are still asking for a model out there that we can just implement here in our church — but there’s no universal model out there.

We are actually the ones who have to do the thing. There are some landmarks, some language, some principles we need to try to embody, but we haven’t corrected this injustice before, and so we literally are the ones who have to figure out what it means. And it’s going to look different in each local context.

It’s new to white people, but there is a different kind of sharing that is happening. And it’s because, I think, of the leadership and insistence and ongoing tenacity of Black Lives Matter movement leaders over the last seven or eight years that we’re getting to this inflection point.

Share