July 11, 2023

Moving beyond creation care to address environmental justice

Therapeutic horticulture is practiced in the healing garden at St. Ambrose Episcopal Church in Raleigh, NC.

Churches called to ministries focused on climate change should also recognize that its impact falls disproportionately on already vulnerable communities.

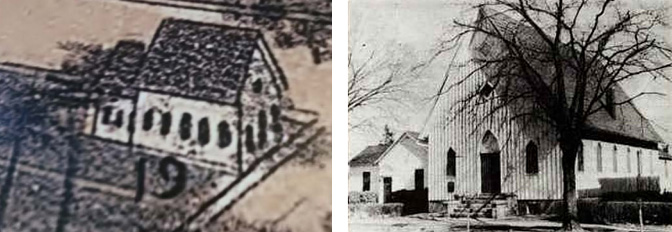

From its founding in 1868 as a parish to serve formerly enslaved people, St. Ambrose Episcopal Church has borne physical witness to the gifts and challenges of place.

The Raleigh, North Carolina, church was first located in Smoky Hollow, an area near downtown set aside for freed Blacks where few people wanted to live, because — as the name described — it lay in a valley polluted by smoke from passing trains.

In 1900, when the city decided it needed the church’s land for a mill, St. Ambrose was forced to move its building, rolling it on logs a mile south.

In the early 1960s, St. Ambrose moved again, to follow a growing Black community hemmed in by housing restrictions. Many of the families had relocated to a community called Rochester Heights about two miles to the southeast.

The only site where the city allowed the church to build, though, was in a flood plain. Walnut Creek, which ran through the area, was prone to overflowing its banks. Worse, the city had dumped raw sewage into the creek for almost 70 years before St. Ambrose constructed its new building alongside it. The city had stopped that vile practice, but the area was such a mess that some people had begun using the creek and surrounding land as an unofficial dumping ground.

St. Ambrose’s history has made it very open to the environmental justice movement, said the Rev. Jemonde Taylor, the rector of the 400-member church.

“We were born out of environmental injustice,” Taylor said. “The city dumped sewage; [others] dumped garbage. Then they dumped Black people.”

Among the church’s efforts was the creation of Episcopalians for Environmental Justice in 1996. The nonprofit group involved itself with cleaning up the creek and surrounding wetlands. Taylor said they removed tires, refrigerators, medical equipment, even cars.

The church sees such work as part of a biblical mandate to be good stewards of the Earth, combined with commands to atone for sin, Taylor said.

“For us, this has not been just a theological exercise; it’s survival.”

Toward environmental justice

St. Ambrose is at the forefront of efforts to get Christians more involved in environmental causes. Often called creation care, such efforts include advocating for policies to stem climate change, encouraging recycling and a green lifestyle, and preventing and cleaning up pollution.

The fight for environmental justice emerges amid the growing struggle in faith communities to recognize and atone for the church’s role in systemic oppressions. In this case, the movement works to ensure that environmental hazards do not fall disproportionately on communities left vulnerable by discrimination and oppressive policies.

Among indigenous communities, for example, deeply grounded religious commitments to the earth continue to be undermined by ongoing harms rooted in colonial abuses. Just last month, the Supreme Court’s ruling against the Navajo Nation regarding water rights that must be negotiated with the state of Arizona has day-to-day implications for the one-third of families on the reservation who lack access to clean, piped water. An already existing crisis there has been exacerbated by a regional drought.

How does the interconnected harm of climate emergency and environmental injustice show up in the landscape of your church or the nearby land? How can your congregation participate in its healing?

Leaders in environmental justice efforts say they are making progress but that their message isn’t always easily accepted. A public opinion poll taken in April 2022 by Pew Research Center threw light on the challenges.

The poll asked respondents how they felt about this statement: “God gave humans a duty to protect and care for the Earth.” Christians overwhelmingly agreed; 92% of those who described themselves as highly religious (those who pray each day, regularly attend religious services and consider religion very important in their lives) expressed support.

But that same survey found surprisingly weak support among Christians for fighting climate change. Only 42% of the highly religious agreed with the statement “Climate change is an extremely/very serious problem.” And only 39% agreed with a core belief of climate change activists: “The Earth is getting warmer because of human activity.”

How could religious people care so much about the Earth but be so unconcerned about climate change? The seeming contradiction is explained by a likely suspect: politics.

As the survey narrative explained: “Highly religious Americans are more inclined than others to identify with or lean toward the Republican Party, and Republicans tend to be much less likely than Democrats to believe that human activity (such as burning fossil fuels) is warming the Earth or to consider climate change a serious problem.”

Who are our sources for wisdom in addressing racialized environmental injustice as we face a new climate reality that confronts all people with impacts of unsustainable pollution?

An expression of faith

The Pew Research Center results did not surprise Avery Lamb, co-executive director of Creation Justice Ministries, a Washington, D.C.-based organization that “educates, equips and mobilizes” Christian congregations and communions “to protect, restore and rightly share God’s creation.” Lamb said he often encounters the impact of politics in his work.

“The biggest difficulties we encounter are our own Christian siblings who have not come to understand environmental justice or creation care as an expression of their faith,” Lamb said.

He said he is sometimes asked what denomination is easiest to work with. “You know, it hardly ever plays out by specific denomination or specific theological tradition,” Lamb said. “It certainly plays out in terms of congregations that trend red or blue, especially when it comes to climate change. … Climate change is politically fraught in this country, and that doesn’t stop when you enter the church.”

Environmental justice seems to be one of the biggest hills to climb for faith leaders in the creation care movement, especially because talking about it brings up potentially divisive concepts such as systemic racism.

Similar to Pew’s seemingly contradictory findings on environmental issues, polling by the market research firm Ipsos in late 2021 showed a disconnect among people of faith on race and racism.

Language and politics as sticking points

Even language can make the work a particularly difficult sell, said the Rev. Mitchell C. Hescox.

“We don’t use the term ‘environmental justice,’” he said. “It has become a loaded progressive talking point in today’s world. What we talk about instead is bringing about fairness to front-line communities.”

As president of the Evangelical Environmental Network, Hescox travels the country spreading the message that people of faith have a special obligation to save the Earth and be kind to the environment. The Pennsylvania-based organization equips and mobilizes evangelical Christians to reclaim “the Biblical mandate to care for creation” and work toward “a stable climate and a healthy, pollution-free world,” according to its website.

Even in conservative communities, Hescox has had success convincing people of faith to be more concerned about the environment, he said. His most effective argument focuses on the impact of climate change on the next generation. “Everybody is concerned with their children and their grandchildren,” he said.

Environmental injustice does not happen only in communities populated by people of color, Hescox said. He noted that any community close to highways and factories or near mining operations, like some parts of Appalachia, can suffer serious health consequences from environmental factors.

Groups in the creation care movement often find success when environmental issues hit close to home. But not all churches feel the impact of environmental problems in their backyards. Across town from St. Ambrose, Greystone Baptist Church is in a mostly white neighborhood that is one of Raleigh’s most upscale areas and has never experienced the kind of human-caused environmental problems that the Episcopal parish has.

In May 2022, the Rev. Chrissy Tatum Williamson, Greystone’s senior pastor, gave a series of three sermons focusing on creation care. “I think it was the first time that we have spent three weeks on a topic that wasn’t what folks would think of as a traditional theological or ecclesiastical topic,” she said.

One sermon focused on the impact of Earth’s rising temperature. Warning the church to “buckle your seat belts” as she began, Williamson said people of faith must “repent and change the way we live.”

She concluded: “We have broken our covenant with God, the one that was given at creation when God gave us the Earth and called us to be stewards of the Earth, and the one that was renewed after the flood.”

As part of the series, Greystone took surveys of the congregation and had group discussions to get reaction. “I think it was received very well,” Williamson said of her congregation, which she describes as “theologically and politically diverse.”

Christian McIvor, the church’s minister of worship, music and the arts, agreed: “There was no pushback whatsoever.”

Williamson and McIvor note that a green lifestyle is well accepted at the church — for instance, recycling bins are prominent, and there is a composting operation out back.

But McIvor added that the church has not delved deeply into potentially more controversial topics. “To start thinking about the systemic nature of environmental injustice …that might raise some questions,” he said.

Healing and resurrection

St. Ambrose’s Taylor acknowledged that it’s easier for members of his church to embrace the environmental justice cause because of its location and history. For some congregations, creation care measures like installing solar panels and energy-saving devices are “cute,” he said. “If you didn’t do those things, your church would be OK. That’s not our reality.”

St. Ambrose has adopted such measures; the church has installed sun-blocking windows and water-saving toilets. But the most important work it has done, he said, has been cleaning up the nearby creek and surrounding wetlands.

“If we had not acted, this church would have been washed off its foundation,” Taylor said.

He said another factor is the vocal support from Episcopal Church leaders. The Episcopal Diocese of North Carolina has made creation care one of its five mission strategy priorities.

“When the top is talking like that, that sets the tone,” Taylor said.

The emphasis on creation care comes from the very top of the Episcopal Church. Presiding Bishop Michael Curry “made it really clear from the very start” that environmental justice would be an important focus for the church, according to the Rev. Melanie Mullen, the denomination’s director of reconciliation, justice and creation care.

How do individual green lifestyle choices mask our collective responsibility to address systemic environmental injustices? How do they inspire collective action?

In 2017, the Episcopal Church began distributing grants for environmental projects around the country; since then, it has given out more than $800,000, Mullen said.

Projects with an environmental justice component are strong contenders for the grants, she said.

“We kind of lean into something we’re learning to express — we don’t give money for gardens,” she said, chuckling. “But we do encourage people to think seriously about relationships. The themes that we teach in racial relations we take seriously in environmental care. It’s great that you have a plan for solar panels or planting an orchard, but we ask that you show us that the grant works toward equity as well.”

The Episcopal Church has adopted a creation care covenant, and one of the pillars of that covenant is “liberating advocacy,” which the church describes in this way: “For God’s sake, standing alongside marginalized, vulnerable peoples, we will advocate and act to repair Creation and seek the liberation and flourishing of all people.”

“I think everyone’s learning to speak a language and acknowledge that there’s a commonality,” Mullen said. “We are stewards of this Earth, and we have to take care to leave no one behind. Our struggles are the Earth’s struggles. We come from different places, but everyone has to realize that in caring for the Earth, we are united.”

What can church leaders do to prioritize the climate emergency in the ministry of the church?

For Taylor, healing is an essential element of St. Ambrose’s environmental efforts. The church has made significant progress in abating the abuses of the past. Dumping has “subsided substantially” since cameras were affixed to light poles near the creek, he said. On a recent visit, the creek’s waters were clear and flowed freely; the banks were thick with vegetation.

“Having a resurrected wetlands heals the community from a mental and emotional standpoint,” he said. “I frame it through the lens of the resurrection. … The wetlands have been a victim of sin against God, against other people, against the land and against ourselves.”

The creek and the community may never be perfect, he said. But “as Christians, we hold up that vision of hope and work to make that more of a reality, realizing that we will not reach perfection until the second coming of Christ and the resurrection of the dead.”

How are environmental and racial injustices linked in your community? How can your congregation work with others in the community to hold these injustices together?

Questions to consider

- How does the interconnected harm of climate emergency and environmental injustice show up in the landscape of your church or the nearby land? How can your congregation participate in its healing?

- Who are our sources for wisdom in addressing racialized environmental injustice as we face a new climate reality that confronts all people with impacts of unsustainable pollution?

- How do individual green lifestyle choices mask our collective responsibility to address systemic environmental injustices? How do they inspire collective action?

- What can church leaders do to prioritize the climate emergency in the ministry of the church?

- How are environmental and racial injustices linked in your community? How can your congregation work with others in the community to hold these injustices together?

Share