May 2, 2023

What happens when an ‘Old First Church’ needs to change?

First UMC of Miami member Don Baggesen stands with the Rev. Dr. Audrey Warren in front of one of two new towers being built on church property. Baggesen was one of the architects of the church's 1980 building, which was torn down to construct the towers.

Eight years ago, First United Methodist Church of Miami faced the fact that its history and prestige weren’t going to keep it alive forever. It has found a way to honor its past and grow into the future.

First United Methodist Church of Miami was Audrey’s second pastoral appointment. She left a deeply challenging and meaningful missional ministry in South Miami to come to the big, shiny downtown church and find some rest, security and stability. She thought.

It didn’t take long to notice that the exterior cross was not shiny but rusty, the roof was leaking, and the sanctuary pulpit had been eroded by termites. The building maintenance list was twice as long as the hospital visit list. So much for rest!

This is the reality of most of our beloved “Old First Churches.” Because First Churches — often, the first of their denominations to be established in a city — are in strategic locations and have significant influence, they have long drawn the attention of observers.

In 1974, Ezra Earl Jones and Robert Wilson wrote a book titled “What’s Ahead for Old First Church?” In their research, they focused on the role of the downtown church in the civic, religious and social life of a city, region and denomination. They noted a number of common traits of Old First Churches — quality, prestige and leadership.

And yet reading their work almost 50 years later, we were struck by the undeniable sense that already in the early ’70s the Old First Church was in decline.

The disestablishment of mainline religion was underway; the function of downtown areas was shifting, especially as the suburbs were growing; and the aberrant patterns of convergent and cohesive communities that had occurred in the post-World War II 1950s were giving way to divergent patterns of social life.

Audrey’s church fit this model, which we included in our 2020 book, “Fresh Expressions of People Over Property.” First UMC Miami’s history is deeply linked to its origins as a downtown church with multiple locations, narratives and identities.

Miami is magical, especially at night. This was not the case 126 years ago, when First United Methodist Church was birthed. The location on the Miami River had been occupied for thousands of years by Native Americans and had been visited by Ponce de Leon in the 1500s; the city itself was incorporated in 1896.

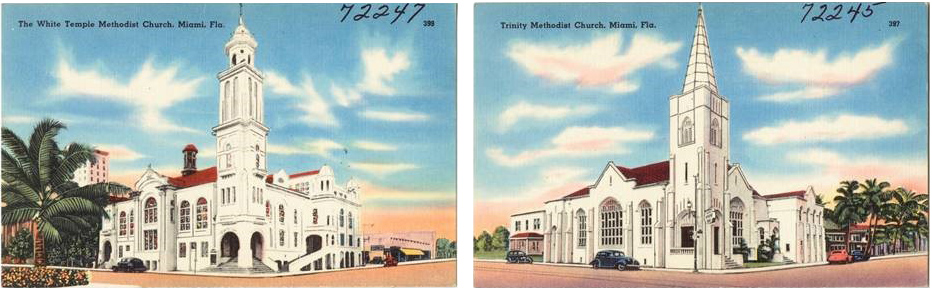

At that time, it wasn’t much of a city, comprising wooden structures, mangrove trees and mud. Many of our early members imagined more; the people who built the city were also the founders of White Temple ME Church (in the northern faction of the Methodist Episcopal denomination) and Trinity ME Church South (in the southern one).

Both churches started in houseboats, then upgraded to buildings and eventually erected their sunbathed sanctuaries just two blocks from one another. The churches had been in their new downtown buildings only about 20 years when the northern and southern Methodists reunited.

Although the two churches were now under the same denominational umbrella and less than a mile apart, they never spoke of merging — they were too big. The growth continued until the ’60s and ’70s. But perhaps spurred by a damaging fire at White Temple, the two churches merged in 1966, meeting at the Trinity campus for several years before constructing a new building on Biscayne Boulevard, completed in 1981.

White flight continued, and by the ’90s, most mainline churches in Miami had lost 50% of their membership. Many wondered what was ahead.

Urban theorist Richard Florida has noted that suburbanization “accentuated [the] fissure of urban areas into separate zones for working and living.” Many of our downtown structures were defined and built for an earlier way of life. But church leaders were slow to adapt to change.

Still, adaptation would come. Many downtown churches simply followed their people to the suburbs; as we know, systemic racism was and is a factor in real estate markets.

Alongside the change came a nostalgia for the past — when sanctuaries and Sunday school classes were filled with people, when prominent preachers held esteemed positions in the community, when political and civic leaders of influence sat in the pews and were active as members.

This selective memory does harm to leadership in the present, lowering morale and increasing anxiety and stress.

When Audrey arrived as pastor of FUMC Miami in 2015, some members still identified themselves as “Templers” or “Trinity.” Many carried with them the nostalgia and prestige passed on to them by the ancestors who had built the city and had stayed when so many others left.

Not all were longtime locals, of course. The faithful folks she inherited were from more than 25 countries around the world, and they also embraced FUMC’s identity “in the heart of the city with the city in its heart.”

The men’s group started a powerful ministry with the unhoused. Many members started tutoring at local elementary schools. The church became a leader in Miami’s People Acting for Community Together and took on many social issues downtown. FUMC’s music was far from contemporary, and its sanctuary bore no screens, but each year new people trickled into the church.

Like many bighearted downtown churches across the country, First UMC found that love was not enough to pay the bills and do new things. Solutions such as budget cuts and renting out space helped for only so long. The church was looking at half a million dollars in upgrades, such as improving bathrooms and organ pipes — expenditures that were necessary but did not bring in new people.

For many churches, large property decisions arise from two main drivers: declaration and desperation. First UMC was motivated by both.

The congregation wanted to stay downtown to declare the gospel and serve the homeless. They also were becoming desperate. Audrey spent her first few months at FUMC crunching numbers. How much square footage was used for ministry? How many of the top 25 givers were over 65? (Answer: too many.)

The questions and the data led to a decision: They had to do something.

How could First UMC remain an Old First Church, willing to understand its past and appreciate its traditions, yet discern what in all of that could be released and repurposed for mission in a changed landscape?

The church formed an exploratory development committee, which created a plan and process to partner with a developer. It then sold a little over an acre to a developer who is building two towers on the property. The church will occupy 20,000 square feet on a corner of one building, and the rest of the building will have 696 microunit apartments, 40 of which will be used as a hotel. The second tower will be residential.

The income received from the sale is being used to buy and build the church’s portion of one building. The rest will be in an endowment to fund the church in perpetuity.

The vision is to have a hub in downtown and spokes in the city. The spokes will be created by the missional and faith needs in their locations, such as a new brunch church directed toward the LGBTQ community or missional ministry with veterans.

FUMC of Miami does not want to stop following God where God might lead them now that they are building a beautiful home. Each year, they’re working to live into a new future for their beloved — new — First Church.

Share