From its founding in 1868 as a parish to serve formerly enslaved people, St. Ambrose Episcopal Church has borne physical witness to the gifts and challenges of place.

The Raleigh, North Carolina, church was first located in Smoky Hollow, an area near downtown set aside for freed Blacks where few people wanted to live, because — as the name described — it lay in a valley polluted by smoke from passing trains.

In 1900, when the city decided it needed the church’s land for a mill, St. Ambrose was forced to move its building, rolling it on logs a mile south.

In the early 1960s, St. Ambrose moved again, to follow a growing Black community hemmed in by housing restrictions. Many of the families had relocated to a community called Rochester Heights about two miles to the southeast.

The only site where the city allowed the church to build, though, was in a flood plain. Walnut Creek, which ran through the area, was prone to overflowing its banks. Worse, the city had dumped raw sewage into the creek for almost 70 years before St. Ambrose constructed its new building alongside it. The city had stopped that vile practice, but the area was such a mess that some people had begun using the creek and surrounding land as an unofficial dumping ground.

St. Ambrose’s history has made it very open to the environmental justice movement, said the Rev. Jemonde Taylor, the rector of the 400-member church.

“We were born out of environmental injustice,” Taylor said. “The city dumped sewage; [others] dumped garbage. Then they dumped Black people.”

Among the church’s efforts was the creation of Episcopalians for Environmental Justice in 1996. The nonprofit group involved itself with cleaning up the creek and surrounding wetlands. Taylor said they removed tires, refrigerators, medical equipment, even cars.

The church sees such work as part of a biblical mandate to be good stewards of the Earth, combined with commands to atone for sin, Taylor said.

“For us, this has not been just a theological exercise; it’s survival.”

Toward environmental justice

St. Ambrose is at the forefront of efforts to get Christians more involved in environmental causes. Often called creation care, such efforts include advocating for policies to stem climate change, encouraging recycling and a green lifestyle, and preventing and cleaning up pollution.

The fight for environmental justice emerges amid the growing struggle in faith communities to recognize and atone for the church’s role in systemic oppressions. In this case, the movement works to ensure that environmental hazards do not fall disproportionately on communities left vulnerable by discrimination and oppressive policies.

Among indigenous communities, for example, deeply grounded religious commitments to the earth continue to be undermined by ongoing harms rooted in colonial abuses. Just last month, the Supreme Court’s ruling against the Navajo Nation regarding water rights that must be negotiated with the state of Arizona has day-to-day implications for the one-third of families on the reservation who lack access to clean, piped water. An already existing crisis there has been exacerbated by a regional drought.

How does the interconnected harm of climate emergency and environmental injustice show up in the landscape of your church or the nearby land? How can your congregation participate in its healing?

Leaders in environmental justice efforts say they are making progress but that their message isn’t always easily accepted. A public opinion poll taken in April 2022 by Pew Research Center threw light on the challenges.

The poll asked respondents how they felt about this statement: “God gave humans a duty to protect and care for the Earth.” Christians overwhelmingly agreed; 92% of those who described themselves as highly religious (those who pray each day, regularly attend religious services and consider religion very important in their lives) expressed support.

But that same survey found surprisingly weak support among Christians for fighting climate change. Only 42% of the highly religious agreed with the statement “Climate change is an extremely/very serious problem.” And only 39% agreed with a core belief of climate change activists: “The Earth is getting warmer because of human activity.”

How could religious people care so much about the Earth but be so unconcerned about climate change? The seeming contradiction is explained by a likely suspect: politics.

As the survey narrative explained: “Highly religious Americans are more inclined than others to identify with or lean toward the Republican Party, and Republicans tend to be much less likely than Democrats to believe that human activity (such as burning fossil fuels) is warming the Earth or to consider climate change a serious problem.”

Who are our sources for wisdom in addressing racialized environmental injustice as we face a new climate reality that confronts all people with impacts of unsustainable pollution?

An expression of faith

The Pew Research Center results did not surprise Avery Lamb, co-executive director of Creation Justice Ministries, a Washington, D.C.-based organization that “educates, equips and mobilizes” Christian congregations and communions “to protect, restore and rightly share God’s creation.” Lamb said he often encounters the impact of politics in his work.

“The biggest difficulties we encounter are our own Christian siblings who have not come to understand environmental justice or creation care as an expression of their faith,” Lamb said.

He said he is sometimes asked what denomination is easiest to work with. “You know, it hardly ever plays out by specific denomination or specific theological tradition,” Lamb said. “It certainly plays out in terms of congregations that trend red or blue, especially when it comes to climate change. … Climate change is politically fraught in this country, and that doesn’t stop when you enter the church.”

Environmental justice seems to be one of the biggest hills to climb for faith leaders in the creation care movement, especially because talking about it brings up potentially divisive concepts such as systemic racism.

Similar to Pew’s seemingly contradictory findings on environmental issues, polling by the market research firm Ipsos in late 2021 showed a disconnect among people of faith on race and racism.

Language and politics as sticking points

Even language can make the work a particularly difficult sell, said the Rev. Mitchell C. Hescox.

“We don’t use the term ‘environmental justice,’” he said. “It has become a loaded progressive talking point in today’s world. What we talk about instead is bringing about fairness to front-line communities.”

As president of the Evangelical Environmental Network, Hescox travels the country spreading the message that people of faith have a special obligation to save the Earth and be kind to the environment. The Pennsylvania-based organization equips and mobilizes evangelical Christians to reclaim “the Biblical mandate to care for creation” and work toward “a stable climate and a healthy, pollution-free world,” according to its website.

Even in conservative communities, Hescox has had success convincing people of faith to be more concerned about the environment, he said. His most effective argument focuses on the impact of climate change on the next generation. “Everybody is concerned with their children and their grandchildren,” he said.

Environmental injustice does not happen only in communities populated by people of color, Hescox said. He noted that any community close to highways and factories or near mining operations, like some parts of Appalachia, can suffer serious health consequences from environmental factors.

Groups in the creation care movement often find success when environmental issues hit close to home. But not all churches feel the impact of environmental problems in their backyards. Across town from St. Ambrose, Greystone Baptist Church is in a mostly white neighborhood that is one of Raleigh’s most upscale areas and has never experienced the kind of human-caused environmental problems that the Episcopal parish has.

In May 2022, the Rev. Chrissy Tatum Williamson, Greystone’s senior pastor, gave a series of three sermons focusing on creation care. “I think it was the first time that we have spent three weeks on a topic that wasn’t what folks would think of as a traditional theological or ecclesiastical topic,” she said.

One sermon focused on the impact of Earth’s rising temperature. Warning the church to “buckle your seat belts” as she began, Williamson said people of faith must “repent and change the way we live.”

She concluded: “We have broken our covenant with God, the one that was given at creation when God gave us the Earth and called us to be stewards of the Earth, and the one that was renewed after the flood.”

As part of the series, Greystone took surveys of the congregation and had group discussions to get reaction. “I think it was received very well,” Williamson said of her congregation, which she describes as “theologically and politically diverse.”

Christian McIvor, the church’s minister of worship, music and the arts, agreed: “There was no pushback whatsoever.”

Williamson and McIvor note that a green lifestyle is well accepted at the church — for instance, recycling bins are prominent, and there is a composting operation out back.

But McIvor added that the church has not delved deeply into potentially more controversial topics. “To start thinking about the systemic nature of environmental injustice …that might raise some questions,” he said.

Healing and resurrection

St. Ambrose’s Taylor acknowledged that it’s easier for members of his church to embrace the environmental justice cause because of its location and history. For some congregations, creation care measures like installing solar panels and energy-saving devices are “cute,” he said. “If you didn’t do those things, your church would be OK. That’s not our reality.”

St. Ambrose has adopted such measures; the church has installed sun-blocking windows and water-saving toilets. But the most important work it has done, he said, has been cleaning up the nearby creek and surrounding wetlands.

“If we had not acted, this church would have been washed off its foundation,” Taylor said.

He said another factor is the vocal support from Episcopal Church leaders. The Episcopal Diocese of North Carolina has made creation care one of its five mission strategy priorities.

“When the top is talking like that, that sets the tone,” Taylor said.

The emphasis on creation care comes from the very top of the Episcopal Church. Presiding Bishop Michael Curry “made it really clear from the very start” that environmental justice would be an important focus for the church, according to the Rev. Melanie Mullen, the denomination’s director of reconciliation, justice and creation care.

How do individual green lifestyle choices mask our collective responsibility to address systemic environmental injustices? How do they inspire collective action?

In 2017, the Episcopal Church began distributing grants for environmental projects around the country; since then, it has given out more than $800,000, Mullen said.

Projects with an environmental justice component are strong contenders for the grants, she said.

“We kind of lean into something we’re learning to express — we don’t give money for gardens,” she said, chuckling. “But we do encourage people to think seriously about relationships. The themes that we teach in racial relations we take seriously in environmental care. It’s great that you have a plan for solar panels or planting an orchard, but we ask that you show us that the grant works toward equity as well.”

The Episcopal Church has adopted a creation care covenant, and one of the pillars of that covenant is “liberating advocacy,” which the church describes in this way: “For God’s sake, standing alongside marginalized, vulnerable peoples, we will advocate and act to repair Creation and seek the liberation and flourishing of all people.”

“I think everyone’s learning to speak a language and acknowledge that there’s a commonality,” Mullen said. “We are stewards of this Earth, and we have to take care to leave no one behind. Our struggles are the Earth’s struggles. We come from different places, but everyone has to realize that in caring for the Earth, we are united.”

What can church leaders do to prioritize the climate emergency in the ministry of the church?

For Taylor, healing is an essential element of St. Ambrose’s environmental efforts. The church has made significant progress in abating the abuses of the past. Dumping has “subsided substantially” since cameras were affixed to light poles near the creek, he said. On a recent visit, the creek’s waters were clear and flowed freely; the banks were thick with vegetation.

“Having a resurrected wetlands heals the community from a mental and emotional standpoint,” he said. “I frame it through the lens of the resurrection. … The wetlands have been a victim of sin against God, against other people, against the land and against ourselves.”

The creek and the community may never be perfect, he said. But “as Christians, we hold up that vision of hope and work to make that more of a reality, realizing that we will not reach perfection until the second coming of Christ and the resurrection of the dead.”

How are environmental and racial injustices linked in your community? How can your congregation work with others in the community to hold these injustices together?

Questions to consider

- How does the interconnected harm of climate emergency and environmental injustice show up in the landscape of your church or the nearby land? How can your congregation participate in its healing?

- Who are our sources for wisdom in addressing racialized environmental injustice as we face a new climate reality that confronts all people with impacts of unsustainable pollution?

- How do individual green lifestyle choices mask our collective responsibility to address systemic environmental injustices? How do they inspire collective action?

- What can church leaders do to prioritize the climate emergency in the ministry of the church?

- How are environmental and racial injustices linked in your community? How can your congregation work with others in the community to hold these injustices together?

A barely noticeable blip in the nation’s consciousness as 2020 began, COVID-19 by March was a full-blown emergency, triggering mass shutdowns, widespread disruption and general havoc.

In Wake County, North Carolina — as in communities across the country — families who relied on the Free/Reduced Meals program to provide healthy food for their children were suddenly without as schools closed their doors.

County officials had long ago recognized the necessity of delivering food to low-income families during the summer, when schools were not in session. They had a program in place for that.

But could they avoid disruption to this vital service during a sudden, pandemic-driven shutdown?

It turns out that they could. But it took an all-hands-on-deck collaboration among an existing coalition of government agencies, nonprofits, businesses, churches and other faith communities to make it happen.

“When the pandemic hit, we were ready,” said the Rev. Stephanie Workman, associate pastor at Kirk of Kildaire Presbyterian Church in Cary, North Carolina, and a leader in the effort.

Within a few days of the schools’ closure, the summer food program pivoted to provide meals to low-income families, she said. By the end of August 2020, they had distributed 154,000 meals. One participant likened it to a “biblical miracle.”

Is your congregation ready as the pandemic continues? Could you retool or expand existing ministries to become ready?

Since 2015, an array of organizations had been building an infrastructure to serve the vulnerable — part of what county official Karen Holmes Morant calls a “network of care.”

Created and led by Morant — who is also a faith leader — and a dedicated group of clergy, it comprises an unusually wide swath of partners, including Presbyterians, Catholics, Episcopalians, Baptists, Hindus and Mormons.

Businesses offer food, and private citizens donate money. Federal, state and local governments offer funding and coordination; between April and June of 2020, the program received $1.2 million in public money.

And food is only part of the story. As needs grew during the pandemic, the program grew to meet them.

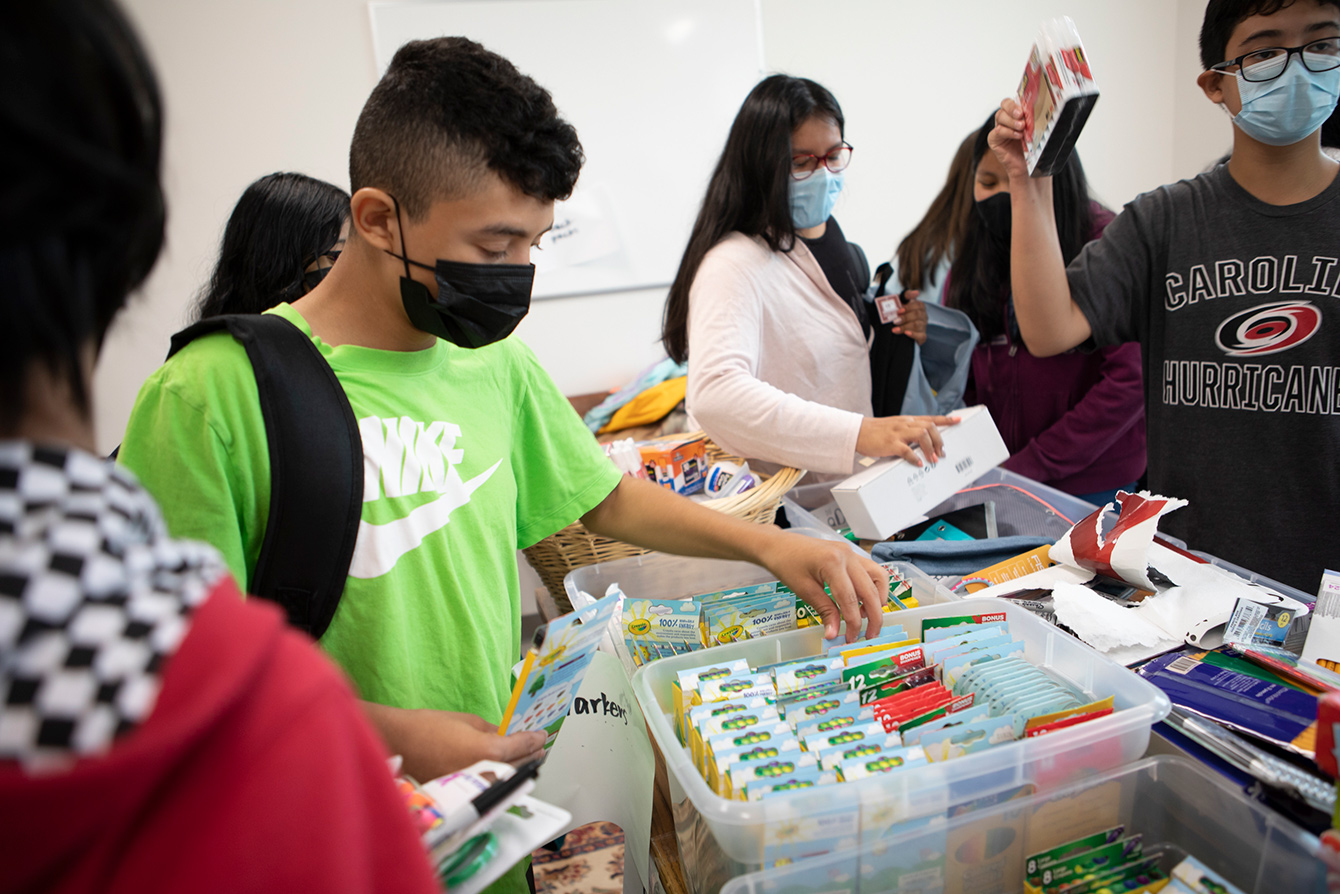

It now includes 12 sites around western Wake County where children get food, have fun, learn English and receive a variety of other services. The meal giveaway sites became places where people could access all kinds of free resources — some 79 tons of fresh produce, for example, and school supplies for 900 children.

Many of the low-income students were being sent home to take online classes yet did not have computers. Organizers obtained 30 donations of used computers, got them into working order and gave them away.

What new work might be possible if you engaged in ecumenical or interfaith partnerships? How might you work with government agencies?

The program has administered 400 COVID vaccinations and sponsored an “Ask the Doctor” day to combat misinformation and answer questions about the virus.

“I knew we had a big-hearted congregation, and all these congregations working together — who doesn’t want to help children, right?” Workman said. “It delights me, but it doesn’t surprise me. … We’ve always said God will provide, and we really and truly go with that.”

Pockets of poverty in a wealthy community

The group’s readiness for a pandemic is even more of an accomplishment considering that the initiative was willed into existence from the ground up, through faith, determination and the buy-in of key leaders.

Workman remembers exactly what she said when she stood up in front of her church in 2015 to call for volunteers for a mission that, at the time, had somewhat blurry outlines.

“Well, Jesus has told us to love our neighbors, and it’s about time we meet them,” Workman told congregants at Kirk of Kildaire.

Her goal was to put into action Jesus’ second greatest commandment — to love your neighbor as yourself (Matthew 22:39; Mark 12:31) — but it was not going to be a simple task. Kirk of Kildaire, a 1,100-member church established in 1977, was more than 90% white and largely professional.

It’s located in the home county of Raleigh, the North Carolina capital. Wake is the second-most affluent county in the state, and Wake’s western region the most affluent of the county.

According to U.S. Census figures, Cary has a median household income of about $105,000, but 4.8% of its residents live in poverty — a fair number of people in a town of 170,000.

The towns in western Wake — including Cary, Morrisville and Apex — are bedroom communities for Research Triangle Park, a 7,000-acre area outside Raleigh that is a haven for high-tech and cutting-edge companies such as GlaxoSmithKline, IBM and Lenovo.

A drive through these towns might elicit oohs and aahs at nice houses; it’s easy to overlook that they have people living in poverty as well. But Workman was among those who were determined not to overlook it.

The neighbors to whom Workman wanted to show a little love were residents in an enclave of apartment buildings about a quarter-mile from the church, occupied mostly by Latino immigrants.

Church members had long been providing tutoring services for those residents, she said, but not much else.

Workman and her fellow members of Kirk of Kildaire joined with Greenwood Forest Baptist Church to launch an effort — dubbed the Summer Program — in which they would provide neighborhood kids with food and maybe help them with English.

They spread the word, put flyers on windshields and readied the church’s fellowship hall for children.

“The very first day, no one showed up,” Workman said. “So Patty and I got in the van and drove around the neighborhood,” she said, referring to Patty Snow, the church’s neighborhood ministry director, who speaks Spanish.

“We got about 12 kids. By end of summer, we had about 100 kids. Moms got on the bus, too, and said, ‘Will you teach us English?’”

How could your church leverage available data to be a better community partner?

‘Having an impact on people’s lives’

The program has helped people like Getsemani Soto, a 17-year-old Cary High School student. For her, the experience was about much more than food.

“I got to meet a million people,” she said. “Yes, this is in my neighborhood, but … It’s a good time to bond, especially if you don’t have a lot to do over the summer.”

The most valuable part for Soto was the Career Project, in which students did research about careers or college.

“It helped guide me to have an idea about what I want to do, potentially,” she said. Soto, who was born in Mexico and came to the United States at age 1, wants to be a child care worker; there will be a big demand for those workers in the future, she said.

Elias Soto, her 14-year-old brother, chose to do the College Project. It helped him clarify his thinking about where he wants to go to college: the University of North Carolina Wilmington.

“I know more about the school because I’ve been wanting to go there for a while now, so it just helped me plan in my mind,” he said.

Their mother also improved her English, the siblings said.

Brian Cruz, a sophomore at the University of North Carolina Greensboro, spent the summer working on the College Project and assisting with food distribution.

“It’s my first time doing this kind of job, so it’s pretty cool,” Cruz said. “This is the only job I’ve had where I’ve been able to have an impact on people. Most of the jobs have been sort of menial, like working at a store — clock in and go home. But [here] you’re actually having an impact on people’s lives.”

Cruz was born in the United States, but his parents are from Mexico and he speaks Spanish. He said he can relate to program participants from other countries.

“I’m first-generation too,” he said. “I can more or less understand what they’re going through.”

‘What can we do to change this?’

What members of Kirk of Kildaire and Greenwood Forest Baptist didn’t know when they started their modest summer program was that someone else also was seeking to address needs in this apparently wealthy community.

Morant is director of Wake County’s Western Health & Human Services Center. She is also associate minister of Pleasant Grove Church in Cary. Both hats fit comfortably on her head.

Morant has religious training (a master of divinity degree from Campbell University), as well as training in both business and leadership and change management (with degrees from Johns Hopkins and Pfeiffer universities).

Her goals can sound preachy — “Get the church out of the congregation and into the community” — but her approach is wonkish: “We use data to drive us and look at what is relevant for this region. … We like to drill down that data and overlay it on the areas on the region of the county that we serve.”

The Rev. Mycal X. Brickhouse, the senior pastor of Cary First Christian Church, met Morant as her vision for a collaborative network was beginning to take shape.

“Karen was a visionary, because she saw the need for the community to be a part of the change that was happening here,” he said.

“She really advocated for faith leaders to operate in the kingdom of God, to operate in this model where denominational affiliation just didn’t matter, where our theological differences didn’t divide us from doing good.”

A study Morant coordinated found that 90% of the residents in that area who were eligible for social services such as WIC and Medicaid were traveling to Raleigh to get them. The study made clear what many local officials and faith leaders already knew, Morant said: people in western Wake needed help.

“Apex, Cary and Morrisville happen to be the wealthiest region in Wake County. … The thought was that government services weren’t needed,” Morant said. “[But] there is hidden poverty in this region.”

Morant was convinced that the government alone did not have the ability to help all of the western Wake families that needed it. The need for a broader approach became clearer when she learned that in the 2016-17 school year, $8 million in state funding for food for low-income children had gone unspent.

She went about creating a “community conversation” among faith leaders, municipal officials and county officials designed to answer the question, “What can we do to change this?”

“I’m looking for transformational leaders in the business sector, the government sector and the church, and also in the community, so we can work alongside each other to redevelop the community,” she said. “Our nonprofits and our churches have always been a great resource in our community.”

This effort swept up a number of churches, including Kirk of Kildaire, and led to the creation of the Western Regional Food Security Action Group, of which Workman is now president. Its goal is to play an active role in the community’s “network of care.”

Morant reached out early to Brickhouse, who shared her strong belief that poverty in Cary was not being adequately addressed and churches had a role to play.

What are some resources — not necessarily money — that your church could bring to a community collaboration program?

“We connected on thinking about how we could work together and bring this congregation in on this project for the welfare of Cary,” said Brickhouse, who is also director of alumni relations at Duke Divinity School.

Brickhouse’s church is one of the initiative’s food distribution sites, serving clients who are African American, white and Asian.

The town, well known for design rules that promote beautification and conformity, requires extensive landscaping that hides eyesores and also obscures poverty, Brickhouse said. “That may not be the intent, but that’s the outcome.”

“The [low-income] neighborhoods are largely hidden behind trees, behind large shrubs and those types of things,” he said.

Brickhouse called the pandemic mobilization something close to a “biblical miracle.”

But the help the initiative provides can be important even on a smaller scale, said Patty Snow, the neighborhood ministry director who’d hopped in the van on the first day of the Summer Program to look for kids.

In an era of COVID, parents have been particularly concerned about official-looking letters, she said. Sometimes, participants take photos of such letters and text them to her, saying, “This looks important” and asking her to translate, Snow said.

“At least now they feel that somebody cares,” she said. “That’s how we want for them to feel — that there’s somebody who has their back in difficult situations.”

Alex Schwindt contributed to this story.

How might you design a ministry so that it meets an immediate need but also lowers ongoing barriers to equity?

Questions to consider

- The Rev. Stephanie Workman said, “When the pandemic hit, we were ready.” Is your congregation ready as the pandemic continues? Could you retool or expand existing ministries to become ready?

- What new work might be possible if you engaged in ecumenical or interfaith partnerships? How might you work with government agencies?

- How could your church leverage available data to be a better community partner?

- What are some resources — not necessarily money — that your church could bring to a community collaboration program?

- How might you design a ministry so that it meets an immediate need but also lowers ongoing barriers to equity?