Teresa Mateus got the call from Charlottesville, Virginia, on the August 2017 day when a white supremacist drove his car into a group of counterprotesters, killing Heather Heyer and injuring dozens of others.

Organizers there asked, “Can you come?”

“They were inundated with all of this trauma,” Mateus said. “And even the providers in the community that had treated trauma for years didn’t know how to treat this kind of trauma, because it was unique and new and specific to social movements.”

Mateus, based in Louisville, Kentucky, is a licensed clinical social worker and trauma therapist by training who teaches spiritual care. And she offers such care for those involved in social movements. The work has history, and world events in recent years have given it renewed urgency.

“The lineage of healing justice going back to at least the ’80s is really the genesis for the kind of work that we’re talking about when we’re talking about doing healing work — spiritual care and social movements,” Mateus said.

Issues like racial justice, women’s rights and the environment have pushed people into the streets and their concerns onto computer screens, televisions and newspaper pages, reaching beyond those actively engaged in protests. Between Jan. 20, 2017, and Jan. 31, 2021, the Count Love project (which tracks public protests through local media coverage) reported 27,270 U.S. protests, with more than 13.6 million attendees.

These protests, and the ongoing activism that happens in less public settings, can be emotional for participants as well as those observing them or living in affected communities. Movement chaplains can help address the distress, sadness and exhaustion that may accompany activism.

“We believe the field of chaplaincy has expanded tremendously. We believe that the way we are called to provide spiritual care is different in 2023; therefore, we believe that movement chaplaincy is the most cutting-edge way of doing chaplaincy in 2023,” said the Rev. Dr. Danielle J. Buhuro, the director of movement chaplaincy for Faith Matters Network. The Nashville-based nonprofit offers resources for connection, spiritual sustainability and accompaniment for community organizers, faith leaders and activists.

“People who are involved in movement chaplaincy take seriously this notion that we are called to care not only for the spiritual, religious or faith needs of a person, but we are called to care also for the social and emotional mental health of patients,” said Buhuro, who is also the executive director of Sankofa CPE Center.

The evolution of movement chaplaincy

How is your faith community present or absent in movements for justice? Why is that?

The Rev. Jen Bailey, the founder and executive director of Faith Matters Network, wrote in an email interview that movement chaplaincy is only one manifestation of work in social movement spaces that centers healing and care.

Movement chaplains offer spiritual, emotional and relational support to people engaged in social justice movements, wherever these people may be. Their work “has its antecedents in the lineage of the Southern Freedom Movement and more contemporary efforts through the healing justice movement,” Bailey wrote.

Mateus also pointed to the “heavy history” of healing justice in the Detroit area. “It’s very important work; it was happening very grassroots,” she said, noting that although the work wasn’t situated in what are considered epicenters of power, “luckily, it’s beginning to rise to the top.”

There is breadth in how the efforts are framed. For instance, the person offering the chaplaincy can be grounded in movement culture and understand activist life and what it’s like to be an organizer, said Hilary Allen, who previously consulted on the movement chaplaincy project at FMN.

Under this definition, the approach that chaplains take is intended to be anti-oppressive, to fit within movement culture, and the person or organization receiving the care also is “grounded in movement,” she said. In this way, the presence of chaplains allows there to be spiritual care in secular spaces.

At the height of 2020’s protests — in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic and the aftermath of the brutal slayings of Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, George Floyd and others — images showed seas of people demonstrating in cities across the country. Related images showed law enforcement officers dressed in riot gear, using tear gas, brandishing batons and pushing back against the crowds — even as almost 95% of U.S. demonstrations during that time connected to the Black Lives Matter movement were peaceful.

Activists continue their work amid the seemingly infinite unfolding of more tragedy, such as the January 2023 killing of Tyre Nichols by police officers in Memphis, and the subsequent release of deeply disturbing videos.

The Rev. Vahisha Hasan, who is based in Memphis as a part of the activist community, is dedicated to providing this kind of pastoral care. After Nichols was killed, his community of fellow skateboarders organized a vigil at a local skateboarding park. There, standing under the night sky surrounded by a crowd, Hasan offered the opening prayer.

What justice issues are people concerned with in your area, and how are faith communities part of the concern? How might they be part of the solution?

She has attended meetings with the district attorney and the Department of Justice, she said, and attended Nichols’ nationally streamed funeral.

Hasan has focused on faith, social justice and mental health as program director at Historic Clayborn Temple in Memphis (the site where activists organized for the 1968 sanitation workers strike) and as executive director for Movement in Faith, a project of the Transform Network that works, in part, to connect people and faith communities with broader justice efforts to practice transformational church and social change.

“In order to do sustainable movement work, we need to have integrated wellness. How do we do this — how do we live and not die? We don’t want the state to take our life. But we don’t want this work to take our life either,” Hasan said. “The overarching framework of my theory of change, if you will, is that we need well people who are doing well work to create well systems.”

In many ways, Hasan is typical of those carrying this work forward.

“Many of the folks who seem most drawn to movement chaplaincy,” wrote FMN’s Bailey, “are those who feel a particular call to accompany those on the frontlines of social justice issues and/or who have some training in pastoral care, mental health, etc., and are looking for ways to deploy their skills in a way that can be nourishing to movement spaces.”

Movement chaplaincy also seems to be growing more common. “We believe that the tide is turning,” said Buhuro, the chaplaincy director. “We see more people working in various forms of social justice chaplaincy than we do folks working in the hospital. … We believe the hospital chaplaincy is no longer the traditional model.”

Accessing training

Training for this demanding vocation is offered by groups such as Faith Matters Network and PeoplesHub. At FMN, students are offered “the opportunity to dig deep into their own traditions of healing and accompaniment while also learning practical skills for de-escalation and mental health first aid that can be of assistance to organizers and activists,” wrote executive director Bailey.

The network’s 12-week course, offered in partnership with the School of Global Citizenry, launched in 2019 and has trained more than 600 participants so far, according to Bailey.

“Students who took the 2022 course were involved in multiple capacities with local, national, and international movements for justice as well as serving as leaders in social justice work in their congregations. The course equipped students to draw from their particular denomination’s spiritual practices as a source for their approach to movement chaplaincy,” she wrote.

Participants have gone on to engage with everything from discipleship groups to social justice committees to anti-racism teams in churches from California to Maryland. Some have also continued to work independently of churches.

“Especially with the training course, we found that a lot of people were interested in movement chaplaincy as a sort of additional skill set or tool set that they’d be able to rely on,” said Allen, the former network consultant. That broad subset of trainees could include people such as social workers, emergency medical workers, attorneys and even teachers, she said.

Mateus, the social worker and teacher, said there are many stages of social movements and many stages of trauma within them.

“I believe there’s a place for chaplaincy and spiritual care at every layer,” she said.

At the time she received the call to Charlottesville, the city already had some resources and infrastructure, Mateus said. When she got to the scene about a day and a half later with a small team, she connected with Unitarian Universalist organizers who had been previous contacts, along with Black Lives Matter leadership, to find a location and hold space for people who needed support. Through word of mouth, Signal chats and other community communications, they opened the space for drop-in hours to allow people to visit.

For her work providing spiritual care, Mateus said, she has integrated creative arts, contemplative practices such as yoga or meditation, and indigenous practices from her own Latinx orientation. She said this kind of care is especially important in communities of color, because there can be a lack of therapists who understand complex identities and the nuances of social movements.

Hasan incorporated breathwork into her prayer at the Memphis vigil. “Breathwork as a form of grounding has been really pivotal for me. And I include it in prayer; I include it as practice,” she said, noting that she also integrates as much communal healing as possible.

What is one creative way that you have offered or could offer support to justice advocates in your area?

When professionals are trained in movement chaplaincy, they can provide more well-rounded care in general. Kenji Kuramitsu, who is based in Chicago, is employed full time as a clinical social worker at an LGBTQ health care center, and part time as a chaplain to a nonprofit. Though his training in chaplaincy is more traditional (he formerly served in a hospital setting), he recognizes the benefits that movement chaplaincy can provide.

During the earlier days of the COVID-19 pandemic, he said, he volunteered as a chaplain to support front-line workers.

“Folks who were themselves ministry, spiritual care, congregational leaders or other kind of providers were feeling as exhausted, as terrified, as uncertain as the communities of people they were serving,” Kuramitsu said.

“Movement chaplaincy has the potential to provide access to spiritual care to populations that haven’t traditionally been served by chaplains,” he said.

Sustaining the work and connecting with communities

Movement chaplaincy can be a way to both reach people beyond church walls and offer those who would not ordinarily attend divinity school a way to care spiritually for others.

“As we know, some people, for whatever reason, it’s their life circumstance, are never going to quite get close enough to those faith communities to be able to access those resources,” Allen said. “Movement chaplaincy may be something that a person could get from a pastor, but they may never step foot inside a church.”

For faith leaders who want to participate in this chaplaincy or help sustain it, Mateus said, understanding the fluidity of these practices can be helpful. Many of those in movements may not come from the Abrahamic traditions, she said.

To help bridge the gap, Mateus said, clergy could go beyond the old model of staying within their own houses of worship.

“You have to be where people are,” she said. “Particularly with social movements, if people aren’t seeing you at meetings, if you’re not at least showing up and saying, ‘I care about what you’re invested in,’ you can’t show up in the moment of crisis and people believe that it’s authentic or that they can trust you. There’s a lot of necessary mistrust in social movements,” Mateus said.

Building relationships with community organizers, asking what kinds of resources they need and being present in necessary ways can build trust, so that when help is needed, organizers can reach out, Mateus said.

Faith leaders also should consider being open to other points of view. “Listen to the organizers and let yourself be led by those who are most proximate to the challenges because they often have the best insight into the solutions that are needed,” Bailey wrote, noting that faith leaders can look for these contacts by searching online for local organizations doing “movement chaplaincy” or “healing justice” work.

Buhuro, who works as a chaplain to chaplains, said she offers support via one-on-one talks, meetups, monthly and quarterly events, and even physical care packages, with items like gift cards, T-shirts and candy. She also spoke to the importance of doing creative, on-the-ground work, pointing to chaplains who spearhead food banks and serve in funeral homes.

“Our movement chaplains work hand in hand with community members to address unemployment, poverty, violence and other forms of oppression in that community. We’re not just wanting to show up when it’s time to provide care to activists on the front line during a rally, a march or a demonstration, but we want to provide long-term, systemic change by journeying with people in the community over a period of time,” Buhuro said, noting that chaplains also can carry out this work by advocating for resources with legislators and clergy.

When chaplains learn to offer these more creative kinds of care, the results can be powerful.

“Movement chaplaincy can serve the spiritual and holistic needs of social justice organizations and their leaders not only in peak movement moments — such as the climax of a campaign, election, or major actions and street demonstrations — but in the in-between times,” the Rev. Margaret Ernst, the director of learning and integration at FMN, wrote in an email.

How can you build relationships and foster trust with secular activists and advocates?

“Movement chaplains can help meet those needs through supporting groups and organizers to celebrate victories, grieve losses, work through conflict, attend to trauma, and facilitate nourishing community care,” Ernst wrote. “Movement chaplaincy should help those who are [on] the front lines of justice struggles to know that they do not have to carry their burdens alone.”

As individuals, faith leaders also can consider stepping out in other ways. “God is bigger than our individual safe communities, our individual churches, our individual institutions. So if God has placed a purposing in you, … then go find the place to be rooted. Do not wither and die where you are,” Hasan said, noting that this growth does not require severing relationships with the people who have been spiritually formative.

“For the collective, for faith communities, I say we need to wrestle more,” she said. “The same wrestle that Black churches had during the civil rights [movement] is not a dissimilar wrestle as today. It is a lie that all Black churches were excited about what MLK was doing and how he was showing up. There were people who absolutely were like, ‘Be quieter; don’t do this; don’t make waves.’ Because what he was doing was dangerous.”

But the stakes remain high. “There needs to be some transformational work that’s happening, and the church needs to see itself in movement,” Hasan said. “And, God bless, the movement absolutely needs to see the church. What it will require is some vulnerability and some deference.”

How are you present in the day-to-day activities of your community beyond church walls?

Questions to consider

- How is your faith community present or absent in movements for justice? Why is that?

- What justice issues are people concerned with in your area, and how are faith communities part of the concern? How might they be part of the solution?

- What is one creative way that you have offered or could offer support to justice advocates in your area?

- How can you build relationships and foster trust with secular activists and advocates?

- How are you present in the day-to-day activities of your community beyond church walls?

At an airy school site in southeast Washington, D.C., several children gather around an outdoor planter filled with espresso-colored dirt. It’s about 3:30 on a bright summer afternoon, and the students have been there since morning.

They began the day with harambee, a high-energy ritual that lets students pull together and celebrate themselves, before going into a sewing exercise and then a nutrition lesson. Now comes the gardening, where they learn a handy fact — how lavender can repel mosquitos — and start to grow their own plants.

As these students — known here as scholars — congregate, a college-age instructor (also known as a servant leader) watches over them while parents and other site staff linger outside and inside the school.

All of this is part of a Children’s Defense Fund Freedom Schools six-week summer session. And since CDF’s mission is “to ensure every child a healthy start, a head start, a fair start, a safe start and a moral start in life and successful passage to adulthood with the help of caring families and communities,” this program is key.

In fact, CDF Freedom Schools, also offered as after-school programs, are the “heart and soul” of what the Children’s Defense Fund is doing for children and their well-being, said the Rev. Dr. Starsky Wilson, CDF’s president and chief executive officer. Through CDF’s partnerships and work with children, families and communities, Wilson said, the program “helps us to prioritize what we’re speaking about, what we’re advocating around, and the policies we believe families need to create the conditions for their children to thrive.”

A program with history

CDF has a record of helping communities. Civil rights pioneer Marian Wright Edelman, credited as the first Black woman admitted to the Mississippi Bar, founded the nonprofit in 1973 after dedicating her early career to defending the civil liberties of people who faced poverty and discrimination.

Today, the CDF Freedom Schools program is offered to students in kindergarten through 12th grade around the country in community centers, schools, juvenile justice centers, churches and other settings. In 2021, more than 7,200 scholars participated in programs in 26 states and 75 cities.

Freedom Schools have their origin in the Mississippi Freedom Summer project of 1964, which gathered college students to work for justice and voting rights for Black citizens. Back then, these college students volunteered to teach younger students traditional subjects like reading, math and science, along with Black history, constitutional rights and other topics not covered in Mississippi public schools, said Kristal Moore Clemons, the national director of CDF Freedom Schools.

How does your congregation nurture the holistic well-being of children and families in your community?

The early Freedom Schools were established to build the next generation of voters, Clemons said, noting that leaders thought that if they could “crack” Mississippi, they could do the same with other Southern states.

“Our faith-based partners have always played a role in the movement,” she said, explaining that most of the original Freedom Schools operated in churches or community centers.

CDF started its Freedom Schools program in 1995 to help children who lacked access to high-quality literacy programs. Each year, many students — especially those from historically disadvantaged groups — experience summer learning loss. Recent literature on this loss has been mixed, according to a 2017 Brookings Institution report, but one theory cited in the report suggests that lower-income students might learn less over the summer because “the flow of resources slows for students from disadvantaged backgrounds but not for students from advantaged backgrounds.”

To support students, the CDF model has five components: high-quality academic and character-building enrichment; parent and family involvement; civic engagement and social action; intergenerational servant leadership development; and nutrition, health and mental health.

How can partnering with a large national project like CDF’s Freedom Schools empower your faith community’s commitments to the young?

Since its start, more than 169,000 children have experienced Freedom Schools, and more than 19,000 young adults and child advocates have been trained on the model, which offers a research-based and multicultural curriculum. The majority of students in 2021 identified as Black/African American (68.4%), with the second-most represented group identifying as Hispanic/Latino (13%).

Because the schools are free to families, parents and guardians don’t incur the expenses they might otherwise have for child care, camps or academic programs. This can be especially helpful in low-income communities.

A vital part of a big mission

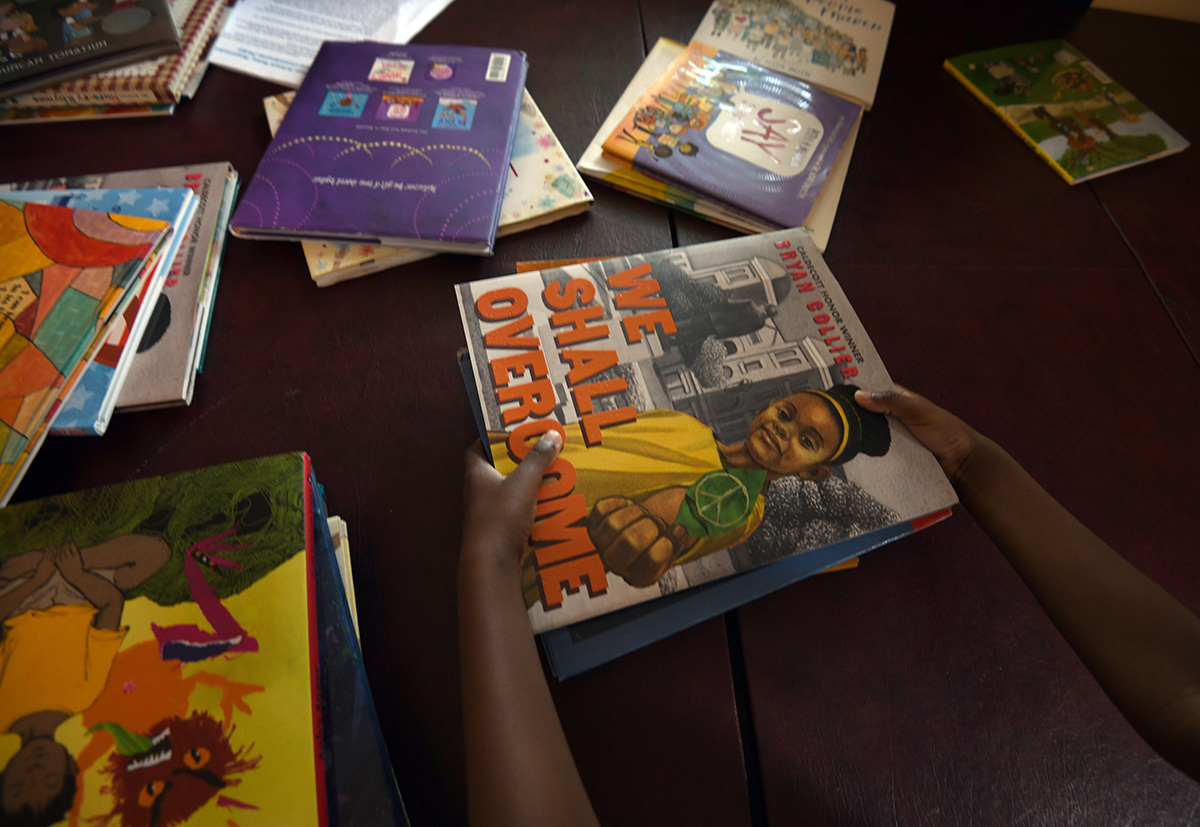

School systems vary state to state, and there can be battles over what is offered in the classroom. For instance, some schools now are dealing with banned books and debates about critical race theory, among other issues, Clemons said.

Children also continue to face changes within the system, such as periods of distance learning and isolation, because of the COVID pandemic. Some students are dealing with news of school shootings and racial injustice as well.

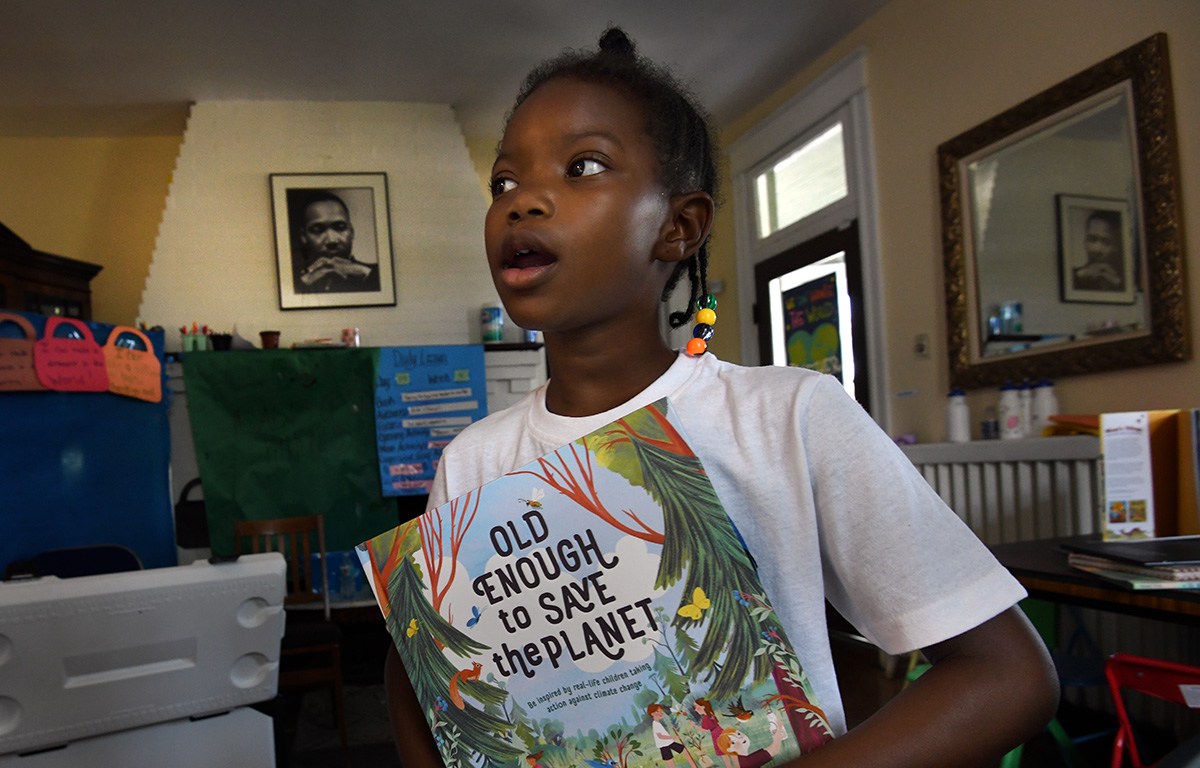

“Every year, we choose a different issue that scholars across the country will organize around and take action on,” said Wilson, the CEO. “This year, we’ve chosen climate justice, because we recognize that the planet is a place that our young people will inherit and that climate justice is racial justice.”

How do the five components of CDF’s model speak to your faith community’s theological understanding of discipleship and the formation of children?

Scholars come together, discuss the issue and share their ideas for solutions on coordinated National Days of Social Action — and they’re allowed to dream, said Joy Masha, program director for the Washington, D.C., CDF Freedom Schools. Scholars might propose a rally, a call to action to a state council member or the creation of more programs for children in their community, among other means of advocacy.

Because educators may not be able to deviate from state curriculum requirements tied to testing, Freedom Schools historically have supplemented content that traditional teachers could not offer, Clemons said. That includes books featuring people of color — important since fewer than 27% of children’s books published in the United States feature nonwhite children, according to CDF — and educating scholars about figures in history.

How does the Freedom Schools model activate young people on issues that matter to them? Why might this matter to your church?

“We don’t want to be controversial. Freedom Schools are not here to break down the status quo. We’re here to be in community with people,” Clemons said.

“We’re here to show children that [if] you want to be a scientist, great. If you want to be a yoga instructor, great. If you want to be the next vice president — because we have books on Kamala Harris — you can do that.”

Some parents say they appreciate the programming and the ability to participate via weekly meetings. Rochelle Gibbons has two children enrolled in the D.C. summer program. If she were to send them to camp instead, they’d simply play, she said. But here they read and build relationships as scholars.

Another D.C. parent, Ashley Jones, said she also appreciates the model. Freedom Schools staff care about the children and the environment that families live in, she said, and teach children that they’re not too young to make a difference.

That lesson is big. Because children are listening. Processing current events. And sharing their thoughts.

Gibbons’ daughter, Dyllon-Rose Gaskin, did just that after her mother spoke at a recent parent meeting in the classroom. The 10-year-old scholar said the program allows her to read books every day and discover new words.

“I learn a lot,” she said, explaining that she’s finding out “interesting stuff” in a fun way.

“Miss Joy has a strong voice, and it helps me speak up sometimes,” she said of Masha’s work at the site.

So what exactly would she speak up about? Dyllon-Rose simply said, “I would speak up about, like, gun violence and different things around the world, like homeless[ness].”

How does it feel to know about these issues as a child?

“People are getting killed … every day, and that’s sad, because people are losing their lives for no reason,” Dyllon-Rose said.

Looking toward a happier future, she shared her desire to be a teacher, a hand model, the vice president, a mayor and “a lot more.”

This kind of exchange, where scholars discuss a range of subjects, is not unusual.

After years of working in the space, Masha said she understands that age does not necessarily determine a child’s experience. Gun violence was the scholars’ issue for 2021.

“As we see more gun violence here in D.C., we know that we can have these conversations with our young people, because our model allows us to do that,” she said. “So if gun violence is a topic that young people want to not only talk about but address, then we explore that solution with them and help them put it into action.”

Within integrated reading curriculum lessons, Freedom Schools use books to explore particular issues and allow scholars to analyze each plot and connect it to the community. Schools also offer parents resources for talking with children about these issues.

The faith connection

To make an impact, CDF partners with various institutions and organizations. To run a program, would-be executive directors apply on CDF’s website and learn about the training, fiduciary and programmatic requirements that accepted sponsor organizations must maintain.

CDF recommends that, at a minimum, facilities be licensed to serve children. Programs then do their own fundraising to bring Freedom Schools sites to fruition, with CDF recommending that programs cover costs for at least 30 scholars.

Since faith communities have a long history of social action and advocacy work, this connection continues to resonate.

Wilson, who also serves on the Duke Divinity School board of visitors, references Jesus’ words with respect to CDF’s work and notes that defending children is “a religious commitment that is resonant with the call of the Christ.”

“For an audience of clergy, I say, ‘If Jesus did not walk among us, then Jesus has less capacity to connect with us,’” he said. “The God that I serve is one who took up flesh and walked with humanity.”

It is this walk that others also highlight.

The Rev. Dr. Van H. Moody II, founding pastor of The Worship Center Christian Church in Birmingham, Alabama, said his church has offered Freedom Schools for several years. He said children in communities of color may not have access to early childhood education, which can put them “behind the eight ball” when they start school. Added to this, summer learning loss can have cumulative effects. But Freedom Schools can help.

“It’s a beautiful program that really checks a lot of boxes that we’re passionate about,” Moody said, noting that it helps kids grow academically, helps them become more well-rounded because they gain a historical foundation, and helps empower them to become conscious changemakers.

His church began supporting the program through funds dedicated to missions, and in recent years has funded it via an endowment, along with public and private partnerships.

“Our faith informs us about how important it is for us to make sure that the next generation not only knows God but that they are prepared to continue to really stand on the shoulders of the preceding generation and to carry the mantle forward,” Moody said.

Birmingham has both a high murder rate and a high violence rate, and many kids are coming from communities where they haven’t seen themselves in a positive light. With these schools, the pastor said, scholars can see the possibilities of what they can be.

“In the Old Testament, the nation of Israel is often taught to talk about the goodness of God and their faith principles with their children and their children’s children,” Moody said. “For us, pouring into the next generation, making sure that the next generation is educated … and prepared to live their best life and affect society in a positive way is an extension of what we believe God has called us to do.”

What can your congregation learn from the Freedom Schools model of formation and community engagement?

Questions to consider

- How does your congregation nurture the holistic well-being of children and families in your community?

- How can partnering with a large national project like CDF’s Freedom Schools empower your faith community’s commitments to the young?

- How do the five components of CDF’s model speak to your faith community’s theological understanding of discipleship and the formation of children?

- How does the Freedom Schools model activate young people on issues that matter to them? Why might this matter to your church?

- What can your congregation learn from the Freedom Schools model of formation and community engagement?

Eight culinary students dressed in black uniforms with chefs’ caps are working carefully at their stations in a spacious commercial kitchen. They’ve already reviewed the proper techniques for cleaning and removing tails from shrimp and cutting fish into filets, best practices for purchasing, and more. Now they’ve prepared and cooked the recipe of the day: cioppino, a classic stew featuring the shrimp and filets along with leeks, in a rich tomato broth similar in color to the students’ red aprons.

As they talk quietly in Spanish, the time comes to present their creations. Culinary instructor and veteran chef Ed McIntosh is not disappointed.

“Beautiful,” he says to one student, studying the stew in a silver-toned pan.

McIntosh offers feedback as he tastes, pulling down his mask to take quick bites.

“Good,” he says to another student, adding a tip to “just watch your shrimp.”

This is a typical day at La Cocina VA, a nonprofit in Arlington, Virginia, that seeks to “use the power of food to create social and economic change in low-income communities.” Founded by Patricia Funegra, the organization works with immigrants, refugees and victims of domestic abuse and other trauma to provide support via job training and placement along with culinary certification.

Though La Cocina VA is not a faith-based organization, it has worked closely with two local churches since its founding. Their collaboration shows how churches can join forces with community organizations to bring about change — offering vital support and partnership to existing innovation rather than independently beginning new church-based ministries. It also provides a model for moving beyond direct service to skill building and community empowerment.

Now housed on land that previously belonged to Arlington Presbyterian Church, La Cocina VA has served more than 200 students in English and Spanish and created relationships with more than 40 food and hospitality partners, including restaurants, markets and hotels. Like many in the food industry over the last two years, the organization also has battled COVID-related challenges, but La Cocina VA has still managed to open an expanded location with a cafe that serves the community.

“We know that we are definitely making an impact in the lives of the people that give us the chance to work with them,” said Daniela Hurtado, the nonprofit’s director of programs and a former chef herself. “There is a huge connection.”

What skills, rather than services, are needed in your community? What can your congregation do to go beyond providing a service?

In the beginning

La Cocina VA has raised more than $2.5 million since 2018 to build out its expanded D.C.-area location — complete with a commercial kitchen with stainless steel appliances, a walk-in refrigerator and a variety of supplies. But as is usually the case, things started smaller.

When she first had the idea to create a nonprofit, Funegra — who was born in Peru and moved to the United States in 2007 — had been working in the nation’s capital. She was employed at the Inter-American Development Bank, helping contacts in South America, Central America and the Caribbean with projects in workforce development, women’s rights and other issues.

But Funegra thought there was more she could do. She began volunteering at DC Central Kitchen, a nonprofit offering culinary programs and job training to formerly incarcerated people.

She started by chopping carrots and onions, and then an idea materialized. She saw so clearly that “this is something that we could offer Latinos, especially knowing the large population of Latino immigrants that work in food establishments,” she said. Funegra worked after-hours to network, research and validate her idea even as she held down her day job.

She eventually registered the new organization and went back to connect with DC Central Kitchen. And she built a relationship with a local community college that could offer certificates to graduates. Along the way, Funegra, now La Cocina VA’s chief executive officer, realized that a church could be a great partner.

“I learned that churches in the United States, especially the older buildings, have beautiful kitchens that are underutilized,” she said. And with that, Funegra was off, knocking on the doors of Catholic churches, Presbyterian churches, “all the different denominations,” she said.

When she connected with Arlington’s Mount Olivet United Methodist Church, things really started to move.

What resources are underutilized in your church?

An initial ‘match made in heaven’

While Funegra was making her rounds, Mount Olivet had already been offering community support, including a ministry to reach out to vulnerable immigrants by providing food.

“But then it became clear that we needed to do more than just provide food,” said Marilyn Traynham, the church’s administrator. “We needed to provide a skill.”

The church had a commercial kitchen, so when Funegra shared her dream, “it seemed like a match made in heaven for Mount Olivet,” Traynham said.

To start, the church managed logistics to ensure that there was adequate refrigerated space and insurance coverage for the project and that related needs were met.

“Mount Olivet has three values, and they’re very important: inclusiveness, making disciples, and reaching out into the community and world,” said the Rev. Dr. Ed Walker, the church’s senior pastor. “While there are a lot of good faith-based nonprofits, there are also equally good nonprofits that are not religiously affiliated.

“When there’s a need, you want to help find a way to meet that need.”

And so they did. La Cocina VA’s first cohort started in 2014, operating in the church’s basement. For several years, Mount Olivet provided not only space for classes but also lunches for students, gifts at Christmas for students and their families, volunteers to help transfer meals to low-income housing communities, and other support.

“[Mount Olivet staff] were so kind. We never paid a dime, not even for toilet paper,” said Hurtado, expressing gratitude to the church.

Students also received additional benefits. As Funegra explained, the program offers full scholarships, so students don’t have to pay for instruction, uniforms or other needs. The program has offered stipends for students without cars or jobs.

Funegra said this kind of help can be “hard to believe at the beginning” for some members of the immigrant population. Building this sense of care is immensely powerful, she said, explaining that in addition to finding jobs, some women have been able to heal or step out on their own.

But as the program expanded, it began to outgrow its church home. In addition to helping participants with their finances and business development, La Cocina VA staff became interested in growth for themselves.

When the opportunity came to move to another space in Arlington, made available when Arlington Presbyterian Church sold its building to benefit the local community, La Cocina VA staff took it. (The church is a recipient of the Traditioned Innovation Award.)

The nonprofit relocated to its new, built-out Gilliam Place facility during the pandemic, pushing through periods of capacity restriction and at times complete closure due to quarantining. Today, if you stroll through their modern, 4,000-square-foot space, you’d never know what they have endured.

Hurtado called the move to the new training and entrepreneurship center “a big accomplishment.” Its new programs include the cafe, which showcases products from the shared-kitchen members as well as La Cocina’s own menu, she said.

Now, the nonprofit has an operating budget of $1,662,000, according to staff members, an active and diverse board of directors, and a new partner in Arlington Presbyterian, which seeks to welcome all and “serve with compassion.”

Mt. Olivet’s relationship with the nonprofit continues, too. Funegra “is a very strong leader,” Walker said, noting that their partnership has worked well because of how Funegra has managed the program.

For churches considering similar arrangements, he said, “my advice would be, make sure the nonprofit has strong leadership.”

When working with this kind of organization, Traynham said, churches should think of the collaborator not as “a building user” but as “part of the ministry.”

A present-day partnership

The new partnership that La Cocina VA has forged with Arlington Presbyterian tracks along an innovative arc for both the nonprofit and the church.

Chartered in 1908, Arlington Pres sold its building and land in 2016 to allow for the creation of affordable housing after the congregation repeatedly heard that many people who worked in the city could not afford to live there, said the Rev. Ashley Goff, the church’s pastor, who now also sits on La Cocina’s board.

The cost of living in Arlington, Virginia, is 44% higher than the national average, and 134% higher when it comes to housing, as PayScale confirms. And in this diverse community, disparities are real, with 6.4% of the population living below the poverty level, according to the 2020 American Community Survey.

The result of the church’s rather sacramental gesture is Gilliam Place, the development where La Cocina is now located. The space’s 173 affordable housing units serve people with low-income, seniors and those with disabilities — and it includes leased space for Arlington Presbyterian, Goff said.

“The call from God to do something about affordable housing was bigger than the building itself, so the building had to go,” she said, harking back to a quote from a church member and explaining that the church is there to be a neighbor.

Arlington Presbyterian buys food from La Cocina VA and contributes financially — including a recent gift of $100,000, Goff said. “We actually discover who we are and who God calls us to be the more that we give away.”

The donated funds continue to benefit students from a range of backgrounds. For instance, a student named Elizabeth, who chose not to share her last name, said she is a trained veterinarian in her home country, but in the United States, she works as a medication aide.

“I would like to also have other options,” she said in Spanish, noting a desire to work independently.

Student Sandra Luz Roman said she enrolled to improve her technical cooking skills, with dreams of opening a little restaurant serving Mexican food.

What might God be calling your church to that is bigger than the building?

Meanwhile, student Wilmer Mejia said he studied chemistry in Peru but now works as a cook in the United States. He said in Spanish that the program lets him learn and is “offering opportunities.”

And those opportunities extend beyond what is taught in the kitchen. For instance, when the morning cooking session of the program concludes on a Friday in May, students straighten up their stations and move to an adjoining classroom to learn about formatting resumes.

When they shift rooms, they leave the kitchen spick-and-span. Bowls are nestled within each other. Large onions are piled in a clear container. Measuring spoons and cups are housed in storage spaces. It’s almost as if the students were never there.

How does your congregation discover who God is calling it to be? How do you discover who God is calling you to be?

And yet the impact of La Cocina VA’s work, and the churches with which they’ve partnered, is clear. The program is teaching Spanish- and English-speaking adults. Matching them with jobs. And creating hope.

As this work continues, Hurtado said, their faithful partners have been huge supporters.

“We definitely feel the love,” she said. “We have definitely been blessed by these two different churches.”

What does a faithful partnership look like for your congregation?

Questions to consider

- What skills, rather than services, are needed in your community? What can your congregation do to go beyond providing a service?

- What resources are underutilized in your church?

- What might God be calling your church to that is bigger than the building?

- How does your congregation discover who God is calling it to be? How do you discover who God is calling you to be?

- What does a faithful partnership look like for your congregation?

On a warm mid-September Saturday, a handful of volunteers sporting casual clothes, orange safety vests and face masks load a wagon with fresh fruit outside Mount Olive Baptist Church. In this secluded Arlington neighborhood mere minutes from the Pentagon, people drive up, and a few walk up, to a folding table in front of the church.

What’s the draw? Church volunteers have gathered to distribute 150 reusable shopping bags filled with fresh cabbage, rice, carrots and whole chickens as part of Mount Olive Baptist’s Olive Cart ministry.

Since early 2020, even as it had to close its doors to in-person worship during the pandemic, Mount Olive has prioritized its food ministry and work with the community. They have seen a need for this help, the church’s senior pastor, the Rev. Dr. James E. Victor Jr., explains, because the food insecurity of some church members and people in the surrounding community has grown.

On this Saturday, as event visitors pick up their items, usually within a few seconds, the residential neighborhood in Arlington, Virginia, is more or less quiet — apart from the friendly chatter of church volunteers and the sound of the occasional plane rumbling overhead.

The volunteers (about 20 in all) have their tasks nearly down to a science, perfected over the many food distributions they have completed since August 2020. The day before, they had gathered at the church to load reusable shopping bags with fresh cabbage, rice and carrots from a local food bank. And they’d stored dozens of accompanying whole chickens, to supplement the food bank offerings, in the freezer.

That prep work paved the way for the seamlessly choreographed final assembly atop green and blue tarps, in a process designed to help recipients get in and out quickly. When the food is all set, the volunteers bow their heads, praying for blessings for the people who will come.

At 10 a.m., when the giveaway event officially begins, cars begin to trickle in, eventually building to more of a flow. The volunteers know exactly what to do.

Seeing the need and taking action

Service is a thread that has run through Mount Olive’s ministries since well before the pandemic, but the pandemic crisis has clarified the community’s needs.

Victor, the senior pastor, says the church serves the community without judgment.

“It’s important, during this unprecedented time in our lifetimes, that the church be at the forefront of serving others in whatever capacities they can,” he said.

The food giveaways are open to everyone, Victor said, calling that work a “sacred act of caring for our neighbors who may be in need.”

The care starts with good quality food. The church either buys produce from a local farm or uses donations from a local food bank, and then purchases protein such as chicken or turkey to supplement the offerings.

What listening practices attune your faith community to the needs of your neighbors?

This year’s September event marked Mount Olive’s ninth food giveaway, said Kimberly Taylor, an associate minister at the church and a key organizer for the food effort. The church held three events in 2020, with the first in August and the second and third for Thanksgiving and Christmas.

In 2021, monthly events have occurred from April through September, and Taylor anticipates two more, again for Thanksgiving and Christmas.

While the food giveaways started during the pandemic, they did not emerge from thin air. Mount Olive sets aside thousands of dollars each year for missions work and offers a variety of programs under its hospitality, outreach and service ministries, with staff seeking to make the church a warm and welcoming place for both congregants and the community.

This work includes ministries for intercessory prayer, sign language services, cooking and fellowship hosting, and more. The church has also provided rental assistance, legal assistance and more to its members, Victor said.

So when the coronavirus pandemic set upon the nation in early 2020, the church’s leadership and members wanted to help. As people lost their jobs, it became clear that many needed a hand with basic necessities like rent and, of course, food.

Victor — a pastor with 30-plus years of experience, with roots in Kentucky — said he and the staff had become aware of certain needs even before the crisis. For instance, when they learned that some local college students were facing food insecurity, the church distributed food like shelf-stable milk and cereal to a Washington, D.C., university.

What sacred acts is God calling your faith community to do with and for your neighbors?

Their pandemic-related mission became clear in April 2020 when Mount Olive was awarded a grant of $10,000 from the Arlington Community Foundation to provide “emergency assistance to low-income and food-insecure residents, including … help with urgent bills.”

Mount Olive staff initially decided to use the grant for food donations and rental assistance. But, as Victor explained, when the 2020 eviction moratoriums kicked in, church staff discovered that the real need was food.

Families had lost wages and employment. Some people were having trouble even getting to the grocery store, and more were having trouble paying for the groceries themselves.

Mount Olive started buying grocery store gift cards for community members who needed food. It was a multigenerational project: they paired older adults and immunocompromised people with younger members who could do their grocery shopping and deliver the food directly to their homes, allowing recipients to avoid being in crowded indoor spaces.

The grant money funded this initial effort, helping 88 households and nearly 200 people in all, Taylor said, but the $10,000 was exhausted within weeks.

Seeing the impact of the food program, and the financial need, church members began donating to the effort to keep it going. And as the need continued and racial injustice issues captured the nation’s attention, the church sought to work with Black farmers who could provide fresh food.

In August 2020, Mount Olive held its first giveaway with farm-fresh produce. Volunteers took careful safety precautions — wearing masks, asking recipients to stay in their cars as food was placed in their trunks, for instance, to avoid close contact. But, Victor said, they also prioritized caring for their neighbors.

“It was a way to balance our faith with the reality of what was going on,” Taylor said, in a community and nation that had been facing not only a pandemic but persistent racial injustice.

The Black farmer connection

The Rev. Palmer Bunting is a Black farmer who inherited his farm, Bunting Farms, from his grandfather Eddie Palmer. In August 2021, a year after that first giveaway event, Bunting shared some thoughts from his tractor while cultivating sweet potatoes.

How can you attend to racial injustice and other systemic inequities while meeting local needs?

Bunting’s farm is in Onancock, Virginia, a coastal area more than three hours by car from the church. He began working with Mount Olive in 2020, as Victor looked to partner with Black farmers so the church could help another population affected by the pandemic.

Bunting’s farm — which also grows collard greens, kale and more — typically sells to churches, grocery store chains, farmers auctions and farmers markets. But when restaurants, markets and churches are closed or at partial capacity, the business can suffer.

“Farming has always been difficult for all farmers, but especially Black farmers,” Bunting said. “Black farmers have not always had access to the resources, the credits or the education that was made easily available to our counterparts.”

Where is God calling you and your faith community to give heartily and generously?

When Mount Olive works with farmers, it matters.

“When they purchase produce from Bunting Farms, it keeps persons employed, it provides revenue for my farm, and it also provides produce to those persons in that community at Mount Olive who are in need of fresh vegetables,” Bunting said.

Bunting Farms staff pack and transport the produce by trailer right to the doorstep of Mount Olive.

For Bunting — a pastor himself who has served at Ebenezer Baptist Church in Exmore, Virginia, for nearly 20 years — the exchange resonates.

“In the season in which we are living, we need to utilize the faith that we have in God to provide us all of our needs,” he said, noting that he is open to working with other churches as well.

“Faith is what produces the crops that I have. … This whole farming operation is one big faith walk.”

By working with Mount Olive on its food program, most recently providing fresh produce for the church’s July distribution, Bunting has seen that faith walk come full circle, he said.

Making a difference

During the food distribution event in September, a home health aide and church member named Linda arrived to pick up some donated food.

Wearing blue scrubs, sneakers and a face mask, she made her way to the front of the church. After greeting the volunteers, she retrieved food for herself as well as some older adults with no transportation.

She explained that the donation would help feed her seven grandchildren who come to visit. The food in her bag would last for about “three cookings, about three different servings,” she said.

Linda would also share the items in her bag with her sons and their families.

“The watermelon — we’ll probably cut it up and we’ll split it,” she said, and they’ll figure out who should receive the chicken. “It’s just a blessing to be able to come and get this food, and then it’s a blessing to be able to serve — help someone else.”

Three servings of food certainly can be helpful, and bags can last even longer for smaller households. These packages — including those given for Thanksgiving in 2020, when the lines of people in need extended for blocks beyond the church — tend to be hearty.

Depending on what the church obtains from suppliers (whether it purchases from Bunting Farms or receives donations from the Capital Area Food Bank), the bags contain fresh vegetables like collard greens, turnip greens, corn and potatoes, along with some shelf-stable products. One giveaway included 25-pound sacks of sweet potatoes.

The church uses donations to make sure there is some form of protein in the bags, including turkey for Thanksgiving 2020, Taylor said.

And if the church doesn’t give all food away during the events on-site, they donate it to people in nearby communities.

“This year, we’ve served over 875 families,” Taylor said, noting that the church has helped more than 3,000 people. And while the number of people served has gone down as some have returned to work, the need is still there.

“If people need to eat,” Taylor said, “we’re still providing food.”

How are the needs in your community changing with the seasons of the pandemic? How can you adapt your responses?

Questions to consider

- What listening practices attune your faith community to the needs of your neighbors?

- What sacred acts is God calling your faith community to do with and for your neighbors?

- How can you attend to racial injustice and other systemic inequities while meeting local needs?

- Where is God calling you and your faith community to give heartily and generously?

- How are the needs in your community changing with the seasons of the pandemic? How can you adapt your responses?