The Rev. Rhonda Thomas already had plenty on her plate as executive director of Faith in Florida.

Her organization, which falls under the national umbrella of Faith in Action, worked on issues of discrimination and disenfranchisement across a broad swath of the state. There was plenty going on before legislation was passed limiting what can be taught, said or read in the state’s K-12 public schools, as well as in its colleges and universities. The consequences have extended nationally to the College Board and beyond.

In Florida, Thomas and others have led a countermovement that has mobilized faith communities to teach what the public schools cannot. Faith in Florida has launched a multipart toolkit focused on topics like race, racism and whiteness, and Black women in leadership, centering faith communities as critical to providing accurate information and anti-racist formation.

Thomas spoke with Faith & Leadership’s Aleta Payne about the effort, which has broadened to other states. The following is an edited transcript.

Faith & Leadership: Could you talk a bit about Faith in Florida?

Rhonda Thomas: We fall under the umbrella of our national [network], which is Faith in Action, and we organize in 41 counties in the state of Florida — multiracial, multifaith leaders working around racial, social and economic justice. We have [statewide] campaigns that we organize, which are immigration, reducing gun violence and mass incarceration, and protecting democracy.

In those counties, we also have our local issues we organize around, whether it be public education, housing, living wages, that sort of thing. That’s who Faith in Florida is. It’s a faith-based organization that just cares about people that are impacted by all sorts of [issues], whether it be legislation, those who have been disenfranchised, those who have been discriminated against — really, really caring about marginalized communities and people in general.

Many people don’t really see Florida as being the South, unfortunately. I don’t know if they get caught up in the tourism or the beaches, the entertainment, the food, but we’re very much the South and as impacted as many other Southern states when it comes to this fight that we’re in.

F&L: How and why did you come to develop the pledge and toolkit around teaching Black history?

RT: We realized that there was an attack on public education as well as our universities on how African American history was being taught in the curriculum and that it was recommended and legislated that it be taught in a watered-down version, implying things that were not true, such as Black people benefited from being slaves.

Faith in Florida decided to do what we do, and that’s organize — organize our faith leaders and see if they will commit to teaching African American history in its realness. You cannot water down history. It is history. I felt personally that our educators were professional enough, whether it be from a public school system or from a university, that they would teach African American history in a way that it was not targeted to offend any race. It would be taught in a professional way through a curriculum that was created.

We felt like, “We’ll take it back to where it originated.” And that’s the Black church, because that history still sits in our pews. That history is still real, and it’s alive. We have always taught our history, maybe not through a curriculum, but we’ve taught it in living color.

I asked my research coordinator to create a team within our staff where we would be able to have resources, whether books or documentaries, that would give our churches the liberty to choose from the toolkit, understanding that we were creating a toolkit that will offer a variety of resources that they can choose from that can fit their own congregations.

It also is a toolkit that will be able to accommodate all ages of people, whether it is children, adults, whether they’re in the church or visiting or never attend but care about the teachings of Black history.

That’s where it all came from. Horrible legislation that came through the state of Florida. We saw where it was not right in the lenses of Black people. The toolkit also gave our faith leaders the liberation to teach it, because the Black church has always been and still is very creative in the way we teach.

It could be taught through biblical lenses, and it could be taught through art, through dance, through music, because that’s just who we’re made up of. Because we organized multiracial, multifaith leaders and congregations, then some of our white churches and mosques, they were like, “We see this is morally wrong. We understand that we may not be able to teach Black history like the Black church can, but we can teach it in a way of accountability.” And that came from our white congregations and white faith leaders. Our Muslim [leaders] understood that we have more in common than what separates us in the way we connect together as a whole. They were willing to teach Black history as well, but still understanding that no one can do it like the Black church can.

F&L: You see this as a moral issue that extends beyond Black Christians.

RT: Yes. We had an open discussion through one of our statewide clergy calls. To try to erase or water down [anyone’s history], to be watered down in a version where it does not represent the truth — it’s morally wrong.

And then Black history itself, recognizing that if we’re not deliberately teaching it in the right form, it also opens [the possibility of] history being repeated, which I do see happening in this country, and definitely in the state of Florida. It’s being repeated. We look at it in the way of how voter suppression still exists. Black people no longer have to go to the supervisor of elections office to guess how many jelly beans are in a jar; now our voting rights are being oppressed and suppressed in the way of [formerly incarcerated] citizens not having the opportunity to register to vote once they’ve served their time in the state of Florida.

F&L: While you started this curriculum for Florida, you have had enough interest from outside the state that there is an effort to broaden it.

RT: My goal was strictly the state of Florida and how do I get 500 congregations to take the pledge to teach African American history. Twenty-eight other states have now joined Faith in Florida under our leadership and are using our toolkit in teaching Black history — 28 states. That was not my goal or vision, but unfortunately, states all across this country were [thinking that] what happens in Florida can possibly happen in their states.

F&L: What do you hope other faith leaders in those states might take from this effort? What do you hope they might take forward?

RT: What has happened here has united faith leaders of many denominations. It has united us under one umbrella to see the importance of Black history being taught. I say it’s being taught raw and being taught real. It is not being taught in a way to offend anyone. If we want to talk about being offended — Black people, we have been offended since the beginning of time. As a Black woman, I would never want to teach anything that would offend others, because I know what that feels like. Seeing the importance of Black history being taught in its own authentic way, we’re uniting communities as well in a faith space, and then also recognizing that we’re operating in the power and the authority that God has given us.

F&L: Is there anything else you want people to know about this work?

RT: This work is great. This work is good, and it’s worth it. You have not asked me whether there has been any resistance. One of our churches has received a bomb threat that came through the police department. Some of our churches are getting called: “Why are you doing this?”

In my church, we have a safety plan in place, even to the point of having active shooter trainings. It’s just unfortunate that this is the way we are looking at how we protect not just the Black church.

Like I said, we organize multiracial, multifaith. There are threats not just on the Black church. Our Jewish community, they’ve gotten threats as well in the synagogues. Our mosques are getting threats. So it also takes us to a place that we have more in common than what separates us when it comes to the faith community.

I don’t think that’s ordained by God, based on my faith tradition, that we should be worshipping in a way that we need to protect ourselves and not be able to worship. Where the spirit of the Lord is, there is liberty. But this is the time we’re living in.

At an airy school site in southeast Washington, D.C., several children gather around an outdoor planter filled with espresso-colored dirt. It’s about 3:30 on a bright summer afternoon, and the students have been there since morning.

They began the day with harambee, a high-energy ritual that lets students pull together and celebrate themselves, before going into a sewing exercise and then a nutrition lesson. Now comes the gardening, where they learn a handy fact — how lavender can repel mosquitos — and start to grow their own plants.

As these students — known here as scholars — congregate, a college-age instructor (also known as a servant leader) watches over them while parents and other site staff linger outside and inside the school.

All of this is part of a Children’s Defense Fund Freedom Schools six-week summer session. And since CDF’s mission is “to ensure every child a healthy start, a head start, a fair start, a safe start and a moral start in life and successful passage to adulthood with the help of caring families and communities,” this program is key.

In fact, CDF Freedom Schools, also offered as after-school programs, are the “heart and soul” of what the Children’s Defense Fund is doing for children and their well-being, said the Rev. Dr. Starsky Wilson, CDF’s president and chief executive officer. Through CDF’s partnerships and work with children, families and communities, Wilson said, the program “helps us to prioritize what we’re speaking about, what we’re advocating around, and the policies we believe families need to create the conditions for their children to thrive.”

A program with history

CDF has a record of helping communities. Civil rights pioneer Marian Wright Edelman, credited as the first Black woman admitted to the Mississippi Bar, founded the nonprofit in 1973 after dedicating her early career to defending the civil liberties of people who faced poverty and discrimination.

Today, the CDF Freedom Schools program is offered to students in kindergarten through 12th grade around the country in community centers, schools, juvenile justice centers, churches and other settings. In 2021, more than 7,200 scholars participated in programs in 26 states and 75 cities.

Freedom Schools have their origin in the Mississippi Freedom Summer project of 1964, which gathered college students to work for justice and voting rights for Black citizens. Back then, these college students volunteered to teach younger students traditional subjects like reading, math and science, along with Black history, constitutional rights and other topics not covered in Mississippi public schools, said Kristal Moore Clemons, the national director of CDF Freedom Schools.

How does your congregation nurture the holistic well-being of children and families in your community?

The early Freedom Schools were established to build the next generation of voters, Clemons said, noting that leaders thought that if they could “crack” Mississippi, they could do the same with other Southern states.

“Our faith-based partners have always played a role in the movement,” she said, explaining that most of the original Freedom Schools operated in churches or community centers.

CDF started its Freedom Schools program in 1995 to help children who lacked access to high-quality literacy programs. Each year, many students — especially those from historically disadvantaged groups — experience summer learning loss. Recent literature on this loss has been mixed, according to a 2017 Brookings Institution report, but one theory cited in the report suggests that lower-income students might learn less over the summer because “the flow of resources slows for students from disadvantaged backgrounds but not for students from advantaged backgrounds.”

To support students, the CDF model has five components: high-quality academic and character-building enrichment; parent and family involvement; civic engagement and social action; intergenerational servant leadership development; and nutrition, health and mental health.

How can partnering with a large national project like CDF’s Freedom Schools empower your faith community’s commitments to the young?

Since its start, more than 169,000 children have experienced Freedom Schools, and more than 19,000 young adults and child advocates have been trained on the model, which offers a research-based and multicultural curriculum. The majority of students in 2021 identified as Black/African American (68.4%), with the second-most represented group identifying as Hispanic/Latino (13%).

Because the schools are free to families, parents and guardians don’t incur the expenses they might otherwise have for child care, camps or academic programs. This can be especially helpful in low-income communities.

A vital part of a big mission

School systems vary state to state, and there can be battles over what is offered in the classroom. For instance, some schools now are dealing with banned books and debates about critical race theory, among other issues, Clemons said.

Children also continue to face changes within the system, such as periods of distance learning and isolation, because of the COVID pandemic. Some students are dealing with news of school shootings and racial injustice as well.

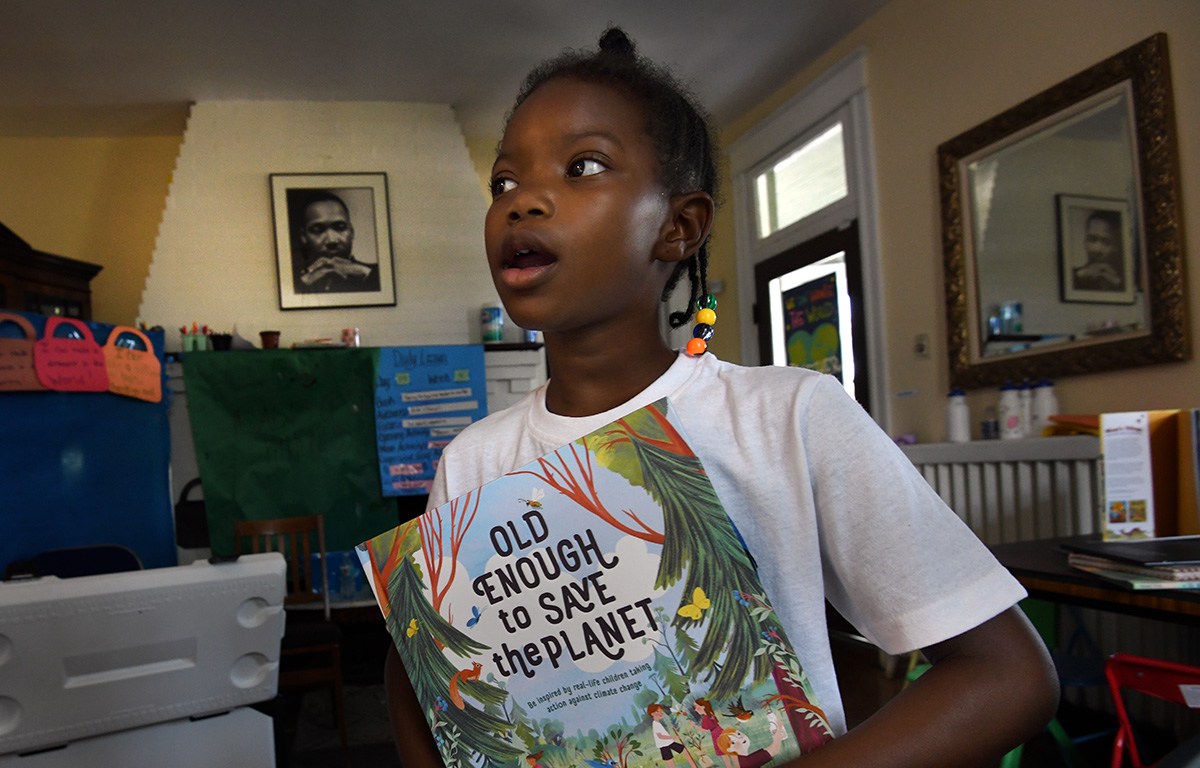

“Every year, we choose a different issue that scholars across the country will organize around and take action on,” said Wilson, the CEO. “This year, we’ve chosen climate justice, because we recognize that the planet is a place that our young people will inherit and that climate justice is racial justice.”

How do the five components of CDF’s model speak to your faith community’s theological understanding of discipleship and the formation of children?

Scholars come together, discuss the issue and share their ideas for solutions on coordinated National Days of Social Action — and they’re allowed to dream, said Joy Masha, program director for the Washington, D.C., CDF Freedom Schools. Scholars might propose a rally, a call to action to a state council member or the creation of more programs for children in their community, among other means of advocacy.

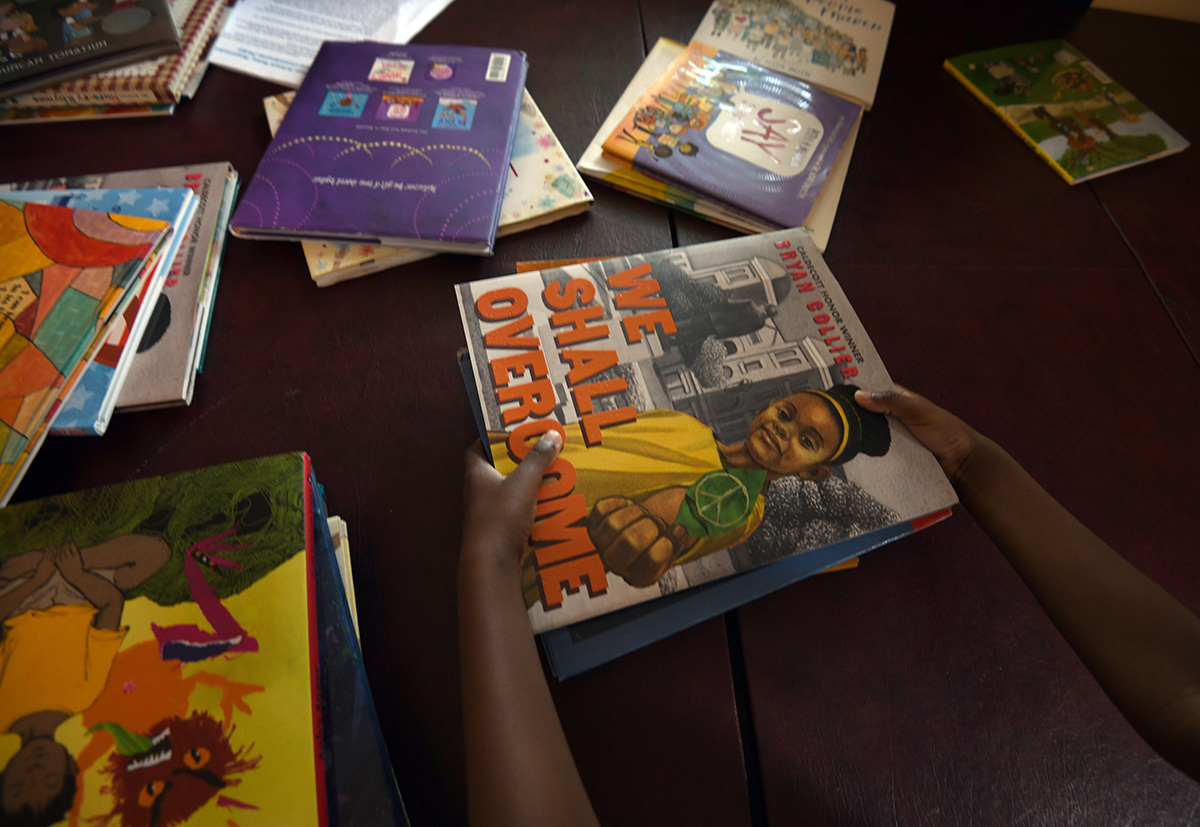

Because educators may not be able to deviate from state curriculum requirements tied to testing, Freedom Schools historically have supplemented content that traditional teachers could not offer, Clemons said. That includes books featuring people of color — important since fewer than 27% of children’s books published in the United States feature nonwhite children, according to CDF — and educating scholars about figures in history.

How does the Freedom Schools model activate young people on issues that matter to them? Why might this matter to your church?

“We don’t want to be controversial. Freedom Schools are not here to break down the status quo. We’re here to be in community with people,” Clemons said.

“We’re here to show children that [if] you want to be a scientist, great. If you want to be a yoga instructor, great. If you want to be the next vice president — because we have books on Kamala Harris — you can do that.”

Some parents say they appreciate the programming and the ability to participate via weekly meetings. Rochelle Gibbons has two children enrolled in the D.C. summer program. If she were to send them to camp instead, they’d simply play, she said. But here they read and build relationships as scholars.

Another D.C. parent, Ashley Jones, said she also appreciates the model. Freedom Schools staff care about the children and the environment that families live in, she said, and teach children that they’re not too young to make a difference.

That lesson is big. Because children are listening. Processing current events. And sharing their thoughts.

Gibbons’ daughter, Dyllon-Rose Gaskin, did just that after her mother spoke at a recent parent meeting in the classroom. The 10-year-old scholar said the program allows her to read books every day and discover new words.

“I learn a lot,” she said, explaining that she’s finding out “interesting stuff” in a fun way.

“Miss Joy has a strong voice, and it helps me speak up sometimes,” she said of Masha’s work at the site.

So what exactly would she speak up about? Dyllon-Rose simply said, “I would speak up about, like, gun violence and different things around the world, like homeless[ness].”

How does it feel to know about these issues as a child?

“People are getting killed … every day, and that’s sad, because people are losing their lives for no reason,” Dyllon-Rose said.

Looking toward a happier future, she shared her desire to be a teacher, a hand model, the vice president, a mayor and “a lot more.”

This kind of exchange, where scholars discuss a range of subjects, is not unusual.

After years of working in the space, Masha said she understands that age does not necessarily determine a child’s experience. Gun violence was the scholars’ issue for 2021.

“As we see more gun violence here in D.C., we know that we can have these conversations with our young people, because our model allows us to do that,” she said. “So if gun violence is a topic that young people want to not only talk about but address, then we explore that solution with them and help them put it into action.”

Within integrated reading curriculum lessons, Freedom Schools use books to explore particular issues and allow scholars to analyze each plot and connect it to the community. Schools also offer parents resources for talking with children about these issues.

The faith connection

To make an impact, CDF partners with various institutions and organizations. To run a program, would-be executive directors apply on CDF’s website and learn about the training, fiduciary and programmatic requirements that accepted sponsor organizations must maintain.

CDF recommends that, at a minimum, facilities be licensed to serve children. Programs then do their own fundraising to bring Freedom Schools sites to fruition, with CDF recommending that programs cover costs for at least 30 scholars.

Since faith communities have a long history of social action and advocacy work, this connection continues to resonate.

Wilson, who also serves on the Duke Divinity School board of visitors, references Jesus’ words with respect to CDF’s work and notes that defending children is “a religious commitment that is resonant with the call of the Christ.”

“For an audience of clergy, I say, ‘If Jesus did not walk among us, then Jesus has less capacity to connect with us,’” he said. “The God that I serve is one who took up flesh and walked with humanity.”

It is this walk that others also highlight.

The Rev. Dr. Van H. Moody II, founding pastor of The Worship Center Christian Church in Birmingham, Alabama, said his church has offered Freedom Schools for several years. He said children in communities of color may not have access to early childhood education, which can put them “behind the eight ball” when they start school. Added to this, summer learning loss can have cumulative effects. But Freedom Schools can help.

“It’s a beautiful program that really checks a lot of boxes that we’re passionate about,” Moody said, noting that it helps kids grow academically, helps them become more well-rounded because they gain a historical foundation, and helps empower them to become conscious changemakers.

His church began supporting the program through funds dedicated to missions, and in recent years has funded it via an endowment, along with public and private partnerships.

“Our faith informs us about how important it is for us to make sure that the next generation not only knows God but that they are prepared to continue to really stand on the shoulders of the preceding generation and to carry the mantle forward,” Moody said.

Birmingham has both a high murder rate and a high violence rate, and many kids are coming from communities where they haven’t seen themselves in a positive light. With these schools, the pastor said, scholars can see the possibilities of what they can be.

“In the Old Testament, the nation of Israel is often taught to talk about the goodness of God and their faith principles with their children and their children’s children,” Moody said. “For us, pouring into the next generation, making sure that the next generation is educated … and prepared to live their best life and affect society in a positive way is an extension of what we believe God has called us to do.”

What can your congregation learn from the Freedom Schools model of formation and community engagement?

Questions to consider

- How does your congregation nurture the holistic well-being of children and families in your community?

- How can partnering with a large national project like CDF’s Freedom Schools empower your faith community’s commitments to the young?

- How do the five components of CDF’s model speak to your faith community’s theological understanding of discipleship and the formation of children?

- How does the Freedom Schools model activate young people on issues that matter to them? Why might this matter to your church?

- What can your congregation learn from the Freedom Schools model of formation and community engagement?

Today, teaching is basically viewed as a matter of technique, says David I. Smith.

“It’s like getting your car fixed at the garage,” he said. “You don’t care if your mechanic is a Buddhist as long as it runs again afterward.”

That view of teaching, however, is fundamentally mistaken, said Smith, a scholar who works at the intersection of faith and learning.

“Always, whatever you’re teaching includes some kind of formation,” he said.

A professor and the director of the Kuyers Institute for Christian Teaching and Learning at Calvin College, Smith said his work “is about recovering a richer sense of what happens when one human being tries to teach another human being and how our beliefs and values get bound up with that.”

A professor and the director of the Kuyers Institute for Christian Teaching and Learning at Calvin College, Smith said his work “is about recovering a richer sense of what happens when one human being tries to teach another human being and how our beliefs and values get bound up with that.”

He is particularly interested in “what being Christian has to do with how we teach and learn and how the choices that we make shape students.”

Before moving to Calvin, Smith, a native of the United Kingdom, was a researcher and teacher educator at the Stapleford Centre, a Christian educational institute, in Nottingham, England. He has a bachelor’s degree from the University of Oxford; a master’s from the Institute for Christian Studies, Toronto, Canada; and a Ph.D. from the University of London. His most recent books include “On Christian Teaching: Practicing Faith in the Classroom”; “John Amos Comenius: A Visionary Reformer of Schools”; and “Christians and Cultural Difference,” with Pennylyn Dykstra-Pruim.

He spoke recently with Faith & Leadership. The following is an edited transcript.

Q: Give us an overview of your work and what ties it together.

I’ve long been interested in what faith has to do with how we teach. It is an issue that needs attention.

To give you an example of what drives my concerns, a few years ago scholars at Baylor University surveyed faculty across 48 Protestant Christian colleges and universities. When asked whether their theological tradition influenced their worldview, their ethics or their motivation for being in the academy, 79 to 84 percent said yes. But when asked whether their theological tradition influenced how they teach, only 40 percent said yes, 40 percent said no, and 20 percent weren’t sure.

For the last 50 years, the conversation about faith and learning has often been about what faith has to do with the content of education, with the ideas that get transmitted. But there’s been much less conversation about how faith affects how we teach — which is strange, because formation comes as much out of how we’re taught as out of what ideas are put in front of us.

I’ve been interested in that from a number of angles, trying to find different ways into thinking about what being Christian has to do with how we teach and learn and how the choices that we make shape students.

Q: Do people tend to think of faith and teaching as two areas that don’t really intersect?

Well, over the past couple of hundred years, we’ve learned to think about teaching as basically technique. It’s like getting your car fixed at the garage. You don’t care if your mechanic is a Buddhist as long as it runs again afterward.

We think of teaching as this collection of techniques that make things work. But that’s fundamentally mistaken. Teaching is much more complex than that.

Always, whatever you’re teaching includes some kind of formation. Partly [my work] is about recovering a richer sense of what happens when one human being tries to teach another human being and how our beliefs and values get bound up with that.

Here’s an example I use when I talk to teachers and want to jump-start them into this topic:

When my son was 16, he came home from school one day — a Christian high school — and said, “I’ve got homework from my religion class. Would you help me study?”

I said, “Sure.” So we sat down and he had a worksheet with 12 words down the left side and 12 definitions on the right. The words were all theological words — “justification,” “sanctification,” “kingdom of God,” “Trinity,” “ascension.” It was the 12 words you need to speak Reformed.

He said, “I’ve got a test on Friday. I’ve got to know this stuff.”

So I started asking him hard questions — “What’s the difference between justification and sanctification, and how would you recognize either one if you found it in your lunch?” “Can you think of a story that illustrates any of these?” “Can you think of a Bible story that goes with any of these?”

He tolerated this for about three minutes before he took the paper from me, tossed it on the coffee table and said in a tone of faint exasperation, “I don’t need to understand it that well, because on the test, they’re only going to make me match the words with the definitions.”

Freeze-frame that moment. Notice he’s doing something dangerous — he’s trying to predict the future. He hasn’t seen the test. The test is on Friday, so what enables him to say with confidence that the test is going to be this way?

What he’s really saying is something like, “Father, you don’t understand. During my time in high school, I’ve noticed certain patterns in the behavior of my teachers, and when they give me worksheets with matching words and definitions, there’s a very high statistical probability that the test is going to be a matching test or a multiple choice test.

“And if that’s the nature of the test, then I don’t need to understand the material. I only need to remember which word goes with which paragraph.”

He’s right. I’ve tried this with roomfuls of teachers. You can translate the worksheet into another language that people don’t speak, and if they’re good students, they can still get 100 on the test just by memorizing the first three letters of each word and the first three letters of each definition.

The teacher in my son’s class is one of the best in his school. I know that the teacher didn’t come into class that morning with a lesson plan that said, “Today I want to teach my students that theology is not important.” Yet the learning outcome was that my son had a list of the 12 most important theological words in the New Testament and he’s saying, “I don’t need to understand this well.”

What taught him that wasn’t anything the teacher said. The teacher did not stand up and say, “Hey guys, this is just theology. It’s not that important so don’t put too much time into this.” That learning came out of the correlation between the structure of the worksheet and the patterns of teachers’ behaviors and their testing strategies.

Yet if I asked that school to show me where it’s doing faith formation, I suspect that they would point me to their chapel program, Young Life, Bible study groups, their faith and learning statement, and so on. And I suspect it would take them a long time to say, “Wait a minute, we do a lot of matching tests based on worksheets. Maybe that’s faith formation.”

I think you’ve got faith formation going on there. My son’s relationship to theology is being shaped by this set of teaching strategies. Something is going on there in the choices that are being made about how to teach.

The problem is not content. You couldn’t get more Christian content onto that sheet of paper without using a smaller font. The problem is with the way the process relates to the content.

That’s the kind of thing I’m interested in. What choices do we make in how to teach? And how does that affect how students receive what we teach?

Q: Your example is from a Christian high school, but what you’re talking about is not just for people who teach in Christian schools, right? All kinds of Christians teach in all kinds of schools, public and private.

That’s right. I started my career teaching in what you would call public schools in England, and I started thinking about a lot of this there. It seemed to me that being Christian was not a thing that gave you Monday through Friday off just because you didn’t work in a Christian institution.

I was teaching in schools where it would be inappropriate to do evangelism, so the question wasn’t whether I had freedom to preach in the language classes I’d been hired to teach. It was more to do with, “I’m a Christian, so how does my identity as a Christian shape the choices that I make in terms of how I shape learning and what my learning goals are for students and how I turn those into learning experiences?”

Any teacher — whether Christian or not — faces questions about how to shape learning in their classroom and how their beliefs and values feed into that.

Q: So how do Christian beliefs and values and commitments shape one’s approach to teaching?

When I started teaching, I taught German, French and Russian in secular secondary schools. Early on, I was struck that the language textbooks I’d been given were pretty much based around consumerism. We spent a lot of time practicing dialogues in French and German where we were buying food in cafes and supermarkets and buying train tickets and theater tickets and going on vacation and talking about our vacation and talking about what clothes we bought.

I gradually thought, “Wait a minute. The picture I’m giving of why you learn other people’s languages is so you can buy stuff from them.”

Then I reflected on the biblical theme of hospitality to strangers. Leviticus 19 says, “Love your neighbor as yourself” (19:18), and then a few verses later, “Love the foreigner as yourself” (19:34). I thought, “If, as a Christian, I think we learn other people’s languages because of the call to love our neighbor and because most of our neighbors don’t speak English, then how would that reshape the examples that I choose, the pictures that I show, the dialogues that we practice, the way I shape a language curriculum?”

When you work at it from that end and you question the underlying values that shape the curriculum you’re delivering, it starts to be possible to come up with alternatives that other people find attractive.

Q: Doesn’t any good teacher think about these kinds of questions, about how they want to shape their students?

In a perfect world, yes. But a lot of things stymie that. Teachers are under enormous time pressure. It’s a very demanding task. They’re under increasing pressure to standardize and meet various external benchmarks and tests, and in the worst cases, it can become a massive exercise in checking boxes and keeping records.

It becomes an exercise in bureaucracy more than an exercise in teaching and learning. It’s like the professionalism of the profession has been downgraded, and teachers are treated as folks who should just make sure that all the bits get covered, and not as people who should be thinking deeply about what they’re doing.

The way we think [most] effectively about our deepest values and how they shape what we do is through engaging in constructive dialogue with colleagues.

It creates more space for self-critique when you can bounce it off colleagues, but in schools, we often end up just teaching in our classrooms and maybe see other people over lunchtime briefly. It’s difficult to carve out time and space for deep collaboration.

Q: What are the values that are implicitly embedded in teaching?

There’s a range of values depending on the context and the area of the curriculum you’re teaching. In the language example, I started questioning the consumerism of curriculum.

Another example from that area is that after a while I realized that the first chapter of almost every language textbook had a cartoon of a person that we would use to name parts of the body as a way of learning to describe people. It’s fun at the start of a language course to be able to say, “My brother is tall and has brown hair,” and it’s also a way of introducing simple sentence structures.

But I realized after a while that the first adjectives that you typically learned were “tall,” “short,” “fat,” “thin,” “athletic,” “unathletic,” “blond-haired,” “brown-haired,” “black-haired.” In other words, we were preoccupied with physical appearance.

The first adjectives didn’t include, for instance, “kind” or “honest.” Again, the bias was toward focusing on external attractiveness. These are the kinds of ways in which a value bias gets built into the choices we make in classrooms.

I’ve seen mathematics [textbooks] where many of the examples are drawn from personal finance or sports statistics. We use mathematics for a lot of other things in the outside world, but again, this consumption-and-leisure cultural model gets reflected in school curriculum.

One of the questions that Christians bring to the table is, What is a human being, and what does it mean for a human being to grow?

Is becoming competent at navigating a consumer landscape and having good leisure options enough for a student to grow? Or do we need to find ways of exploring how the skills that we’re learning fit into other aspects of human experience?

Q: So it’s almost as if the teacher’s own Christian formation enables the teacher to see the underlying values that you saw?

One would hope so, if teachers are receiving a thick enough formation in their own Christian discipleship to be asking questions that go beyond the stories of the world of advertising. It ought to push us to ask these basic kinds of questions about what are we doing and why.

Q: In hindsight, was there something unique about teaching languages that opened your eyes to this?

Yes, I think so.

What drove me into questioning this was that I became a Christian as an adult and I became a teacher a couple of years later, and then I had to figure out what those things had to do with each other.

It wasn’t just that I didn’t teach religious studies or Bible class. In my earlier years as a Christian, I had started to internalize a theology that implied that if you were a serious Christian, you would be a missionary or a pastor or at least teach Bible class. But I found myself teaching languages with a very clear sense of calling, so I had to figure out what it would mean to be a Christian as a language teacher rather than as a Bible teacher.

I found that there hadn’t been a whole lot of thinking about that, so there weren’t answers already laid down. I had to try to figure it out from the beginning.

This stuff becomes vivid when you look at it historically. I looked at four language textbooks at roughly hundred-year intervals over the last 400 years — one published in the 1650s, one from the 1730s, one from about 1900 and one from just a few years ago.

In the one from the 1650s, the first chapter is “Invitation to Wisdom” and the last chapter is “The Final Judgment.” In the one from 1730, the first chapter is “Things” and the last chapter is “Interjections.” In the one from 1906, the first chapter is “The Definite Article” and the last chapter is also something grammatical — adjectives or something. In the one from just a few years ago, the first chapter is something like “Myself and What I Do: Possessions and Pleasures.”

So we’ve gone from wisdom to things to the word “the” to possessions and pleasures as the opening chapter of these language textbooks. You can track the history of social change through the pages of school textbooks. But until you step back and question it, that doesn’t feel strange to us, because it’s the water we swim in.

Q: What’s the overall message from your work for those who teach?

That teaching isn’t just technique. That the choices we make in the classroom have formative effects on students that need unpacking in lots of ways.

Teachers get to make choices about who speaks to whom and under what terms of engagement and what we talk about and what pictures we see and what examples we hear and what stories we’re invited into and what skills we get to try out and what things get left silent and never mentioned and what things we don’t get to develop.

So for teachers to be responsible for those things requires us to ask questions and invite others to evaluate what we’re doing in terms of what is implicitly being said through the teaching choices that we’re making — not just through our words but through the way we structure the learning environment. There’s a basic taking of responsibility, and that can only happen in some kind of community. It requires conversation with one another.

Christian teachers ought to have resources to draw upon. They believe in the body of Christ and being our brother’s keeper and encouraging one another, but that is not always operationalized very well in terms of seeing our calling as something that we work out in community with others who share that calling.

Q: You also study how new technologies are reshaping education. Tell us about that.

Five years ago, we put together a project to look at technology in faith-based educational environments. We weren’t very interested in questions like, If you give kids laptops, will the math scores go up? We were much more interested in questions like, If you give kids laptops, what changes in the educational culture? In relationship patterns? In students’ experience of maturation? If it’s a Christian school, what changes in the way the school understands discipleship and Christian community?

We spent several years gathering data in five schools and were able to build up a rich picture of what was happening across a period of time in a school that had invested heavily in digital technologies.

It was a large project with a lot of different findings, but here are a couple that are interesting.

When we talked to parents, they had worries about social media, cyberbullying and pornography. They were concerned that as students spent more time with digital devices in their learning, it increased their risk of exposure to those things.

What we found was that, if anything, the school was having a positive effect on students’ exposure to those things. The students reported lower levels of engagement with pornography, for example, than averages reported in national studies, including averages for professed Christians. The schools’ efforts to teach students responsibility with technology use seemed to be paying off.

But what we did see all the time — probably the No. 1 abuse of technology that we saw — was students shopping in class. There were lots of examples of students in class with their devices and they’re on a shopping site, maybe window-shopping rather than buying things.

One student said that it was great to learn with laptops, because you can type faster, which meant you can get through the assignment quicker and then “when I’m done, while the teacher is talking, I can go shopping.”

And this is from a Bible class. So if you’re asking questions about faith formation, what faith formation is taking place?

Q: It shows us the consumerist education you were talking about. It’s working.

Exactly.

Until recently, advertising wouldn’t pop up in the middle of your math textbook, but now that students are learning on devices, you can access the shopping wing of the internet in the middle of class and browse stuff.

Yet we found that if students came upon pornography or other kinds of what they called “bad stuff” on the internet, they knew they should close their laptop and call a teacher over. But we didn’t hear any of that with the shopping. They were pretty open about it, because shopping websites are not bad, right? They’re not the websites that their parents are worried about, so for them, it seemed perfectly justified to spend 10 minutes shopping in class.

Another finding was how, just as technology is eroding the boundaries between work and leisure, it is raising questions about how much of the day the school is responsible for students.

If a student emails the teacher at 11:30 p.m. for help with homework, should the teacher respond? A lot of the most dedicated teachers were responding, which meant that there was no time when they were not at work.

If your students turn in homework electronically and it’s time-stamped at 2 a.m., is the teacher responsible to engage that, or is that the parents’ responsibility? Teachers told us stories about parents emailing them at 10 p.m. and then asking at the school door the next morning if they’d dealt with it yet. Or a parent texting in the middle of class that “I’m picking up my student in 15 minutes.”

It’s this expectation of instant response from parents via electronic communication. It’s the ways in which digital communication is eroding boundaries between home and school and who is responsible for the student when. Without clear shared expectations, it created pressure for the teachers to engage in the most heroic behavior.