While various denominations have established policies regarding women’s roles, the number of women serving in religious leadership capacities has surged in recent decades.

According to research conducted by theologian Eileen Campbell-Reed, 20.7% of American clergy were women as of 2016 — up from 2.3% in 1960.

The Evangelical Lutheran Church in America, which represents 4 million members, reported in 2022 that 40% of its pastors were women. In the Assemblies of God, 27.6% of its ministers currently are women.

The Rev. Dr. Kamilah Hall Sharp, who is affiliated with the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ), exemplifies a growing trend among women embracing roles as congregational leaders. Even as some question whether — and how — they should lead, women like Hall Sharp are pursuing alternative pathways to their religious calling.

Hall Sharp, along with the Rev. Dr. Irie Lynne Session, co-founded The Gathering, a womanist church in Dallas. The two ordained ministers planted the church in the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ) denomination, after determining that they could fill a void by bringing to the forefront Black women’s voices. On its website, The Gathering describes its context this way: “As more preachers, pastors and ministers of the word intentionally do the deeper exegetical work of interrogating the sacred biblical texts to raise up the muted voices of women, the theological landscape for womanism continues to expand.”

“We obviously still see women who are having to fight to be in spaces and to be affirmed in spaces,” said Hall Sharp, who also is the director of the Doctor of Ministry in Public Ministry Program at Chicago Theological Seminary. “But I also see a trend in which women are welcomed and starting to create their own tables. My church is an example of creating your own table — within a denominational setting.”

Hall Sharp, a former practicing attorney, pursued a theological degree because she felt a call to ministry. After earning her master of divinity at Memphis Theological Seminary, she moved to Texas to pursue a doctorate in biblical interpretation with a focus in Hebrew Bible at Brite Divinity School.

Despite her credentials, she encountered roadblocks. “In Texas, there aren’t a lot of spaces for women,” Hall Sharp said. “I struggled with finding a church home for a while.”

As a result, Hall Sharp and Session started brainstorming about creating a new space where people could experience womanist preaching. “It eventually evolved into a church. Because we’re both ordained in Disciples of Christ, it became a new church of Disciples of Christ.”

The two didn’t initially consider planting a church. “As it is for a lot of women, we started the church out of necessity,” said Hall Sharp, who co-authored the book “The Gathering, A Womanist Church: Origins, Stories, Sermons and Litanies.”

“We didn’t have support from our denomination to start the church. And even when we did get financial support, it wasn’t a lot,” she said.

The Christian Church (Disciples of Christ), which has ordained women since the 1880s, recently appointed the Rev. Teresa Hord Owens to a second term as general minister and president in the United States and Canada — the first person of color and second woman to lead the denomination — but women continue to have fewer opportunities than men, Hall Sharp said.

In her experience, she said, women are typically assigned to or hired at churches that aren’t able to pay as much. “As a result, they’re never able to really be a full-time pastor,” Hall Sharp said. “So many women in ministry have to have other jobs, because they typically don’t get the churches with all the resources.”

Hall Sharp’s experience highlights a common theme of continued inequity among women taking on leadership roles, according to Campbell-Reed, a visiting associate professor at Union Theological Seminary in New York and co-director of the Learning Pastoral Imagination Project.

“Many women are doing great, but there’s still controversy and conflict everywhere they go,” Campbell-Reed said. “We still have inequities in pay and disparities about where women can start and the extent to which they can grow. They’re still more likely to get associate roles or roles in very small churches.”

Rabbi Dr. Rachel Mikva, a professor of Jewish studies and the senior faculty fellow of the InterReligious Institute at Chicago Theological Seminary, has observed similar patterns in rabbinic roles. She noted that women are leading two of the major rabbinic seminaries. In 2020, Jewish Theological Seminary appointed Shuly Rubin Schwartz as its new chancellor — the first woman to hold the role since its founding in 1886 — and Rabbi Sharon Cohen Anisfeld became president of Hebrew College in 2018.

Those types of developments obviously have been helped by women’s movements across the United States, Mikva said. “However, it’s not without bumps. Women have been moving into rabbinic positions, but not every community was immediately ready to hire a woman to be the rabbi,” she said.

While planting The Gathering was challenging, Hall Sharp said, the rewards were worth it. She said one of the major benefits was providing other women a platform to develop. “It’s difficult to create new spaces, because you don’t necessarily get the financial support that you see others getting,” she said. “But it’s been very rewarding, because people have found a place where they can feel whole; they can come as their complete selves.”

Hall Sharp envisions a future in which women are embraced in their roles as leaders. “I hope to see more women be OK with who they are, to be able to walk authentically, and to see more spaces where they are affirmed and appreciated and their leadership is respected,” she said.

As a millennial who came of age in the early years of Facebook, I hold a complicated relationship with social media. While I appreciate the connectivity that it creates — the ability to meet people from around the world and sometimes build genuine relationships — I dislike how it serves as a vehicle to present images, videos and messages that can push me to a place of envy and low self-worth.

Recognizing that social media was created as a form of self-directed mass communication that allows people to bypass the channels set up by institutions, I also understand that it affords extreme creative liberties that can cultivate toxic desires to appease an audience in hopes of affirmation.

In a season of ever-increasing division, social media presents an opportunity for Christian leaders to share their perspectives on policies, legislation and social norms in ways that direct people to their understanding of what God is saying.

These platforms allow people to rapidly publish their thoughts, ideas and opinions, relatively unencumbered by censorship — or checks for credibility. While the immediate feeling of uninterrupted thought may create some sense of freedom, in reality, no one can express opinions without consequences.

Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, TikTok and Snapchat — you and your congregation probably have at least one of these. Technology has always been a useful medium for faith leaders to spread the gospel to communities, so it is not surprising that we have embraced social media platforms as an essential tool in our ministry.

The mandated COVID-19 lockdowns made social media a necessity to communicate with faith communities while physical gatherings could not take place. But with an uptick in our posting, tweeting and creating reels to stay in regular contact with our congregations, this rapid expression of published opinion calls for a theological ethic that guides faith leaders’ involvement on social media.

How can social media be ordered to generate a common life with God and neighbor as we seek to bear witness to Jesus Christ in the world? This task should be grounded in the virtue of humility.

It has taken me years to remember that my identity is not affirmed through what I post or share on platforms. As a Christian leader, I have had to recognize that embracing the world’s affirmation can lead to a life and ministry of trying to please everyone, allowing my public witness to drain the energy needed to accomplish the work of God’s desired plan.

Social media platforms are an extension of voice that must be managed as such. Our voices are tools for how power is wielded in society. Audiences can perceive our voices through the offices we hold, so we must always use them as instruments to give witness to God’s involvement in our communities and our lives.

Humility is essential, because it is the recognition that all we are, all we have and all we will ever be or obtain is a direct result of God’s provision and sustenance. Christian leaders should not disregard how, even in social media, a posture of humility is a tool to reject the false notion that success is possible without total reliance on God. To embrace humility is to fight against the celebrity culture often associated with social media, which can entice modern-day Christian leaders to boast of their social media following and the expansive reach of their digital platforms.

As our audience grows, our impact is amplified. By office, Christian leaders have an inherited audience on social media, which gives us the ability to influence users and even change their mindset, character and attitudes. This influence can go toward good (what some researchers call “reality perception”) and ill (what they call “deceiver perception.”)

Audiences can perceive our voices through the offices we hold, so we must always use them as instruments to give witness to God’s involvement in our communities and our lives.

Positively, leaders can present solid facts and data through social media that illuminate reality — informing people and helping them learn to give their opinions appropriately. Negatively, leaders can present false “facts” and data that promote deception — misinforming people and encouraging them to malign others’ character, sowing chaos and cultivating an environment with limited tolerance.

Christian leaders have always been influencers, and as such, we have participated in either illuminating reality or promoting deception. The voices of Christian leaders have always carried a burden of responsibility. In “Three Books on the Duties of Clergy,” St. Ambrose wrote, “Let there be a door to thy mouth, that it may be shut when need arises.”

The influence that Christian leaders carry on social media platforms is another form of power that can be used responsibly or manipulated. If Christian leaders are called to help curate and cultivate systems and communities where people can bear faithful witness to God, then our social media engagement needs to be seen as a place where we express faithful discipleship.

In speaking for God, the prophet Isaiah recounts, “The Lord God has given me a trained tongue, that I may know how to sustain the weary with a word” (Isaiah 50:4 NRSVUE).

In using our voices to speak to societal ills, we need to cultivate a practice of humility that allows for prayer, reflection and intentionality. Just as we prepare our sermons, presentations and publications, our social media posts should seek to sustain the weary with a word.

Growing up the daughter and granddaughter of ministers, Thema Bryant was introduced early to the heavy responsibility placed on pastors for mental health counseling. The urgency was as close as the calls to her family’s home phone.

Generations of Bryants have served the African Methodist Episcopal Church, and she followed that path to become an ordained elder. Bryant also pursued a call to become a mental health care professional, earning her doctorate in clinical psychology at Duke University. She now leads the mental health ministry at First AME Church in South Los Angeles and is the president-elect of the American Psychological Association.

“I really do appreciate the blessing of my family. I was able to learn so much simply observing them and participating in the various aspects of the church. The AME Church is really founded on — along with the gospel — liberation and social justice, and that has been integral to my work,” she said. “It also is very much based in being of service to the community. It’s definitely not the kind of church that just opens on Sunday morning for two hours.”

Earlier this summer, Bryant spoke with Faith & Leadership’s Aleta Payne about how her two vocations intersect and about ways the church can grow increasingly responsive to the community’s mental health needs. The following is an edited transcript.

Faith & Leadership: Could we start by talking about your family’s relationship to the church and your relationship to the church?

Thema Bryant: My grandfather, Harrison James Bryant, was a bishop in the African Methodist Episcopal Church, and my grandmother, Edith Holland Bryant, engaged in missions work, community work, and did both social work and also promoting health within our community.

My father, John Bryant, became a bishop in the AME Church. When I was growing up, he was the pastor of Bethel AME Church in Baltimore, which was the largest AME church in that area. As a bishop, his first assignment was to have oversight for churches in West Africa. As a family, we moved to Liberia, West Africa. It was my mother, my father, my brother and I.

My mother, the Rev. Cecelia Williams Bryant, has over 40 years of women’s ministry in the AME Church, hosted many women’s conferences, has written several women’s devotional books, one of them being “I Dance With God.” My parents are now retired.

My brother is a pastor now, in Atlanta, Georgia, of New Birth Missionary Baptist Church. Before he became the pastor there, he was the founding pastor of Empowerment Temple AME Church in Baltimore.

F&L: How did your background and religious formation contribute to your decision to pursue psychology?

TB: My father was very active with pastoral counseling; we often had people calling the house. I talk about this in my book “Homecoming” — that my first time working a crisis hotline was in my home growing up as a kid, because people are more comfortable reaching out, often, to their pastor than reaching out to a therapist. I’m glad we’re having some progress in that area, in terms of destigmatizing mental health.

But I was aware of pastoral counseling and just have always had a heart for people. As a child, I would have been called sensitive. I could feel things deeply, and when I learned that it was a career in and of itself, I felt very drawn to it. When I got to Duke University, in that second year when you need to declare your major, I was very clear in my commitment to psychology.

F&L: Can you talk about the stigma associated with mental health needs and how you think we overcome that?

TB: There’s the grassroots aspect of that, and then there’s the policy piece. On a community level, what really helps destigmatize it is both a bottom-up and a top-down approach. The top-down approach is people who are considered to be leaders in the community speaking up about mental health — even perhaps speaking up about their own use of therapy or the importance of addressing mental health. I think that gives people permission and a freedom to know that it is not shameful.

I used to attend a church where the pastor very openly talked about going to therapy and talked about also her recovery from addiction. That created an atmosphere of transparency, where a lot of people felt that it was OK then to name challenges and to go and get help and that it was very encouraged.

A number of churches now have counseling centers, whether that is with laypeople who have gone through training or whether with licensed professionals. People have to look to see who is providing the care, but even those [programs] that are led by laypeople, I think, can often be structured in a supportive way — like a support group around bereavement that’s based in the church. Sometimes they will have it around recovery or around trauma.

From the bottom up, even when people don’t have leaders who are speaking up about it, we see many more people talking about mental health and about their therapists, even in social media and among their friends. That helps open the door for other people to either say, “Oh, I have a therapist, too” or, “I wonder what that would be like. Tell me about why you went or how that helped you.”

That brings up policy and the need to continue to advocate for support for people to access mental health care, as is the case with physical health care. That’s one of the things I appreciate about the work of the American Psychological Association. Not only do we have researchers, practitioners and educators, but we also have psychologists and staff that are involved with advocacy to try to really promote access to quality mental health care for all people.

F&L: Churches are natural places for both direct service and advocacy. They’re central to communities. We would hope that they are places people see as compassionate and caring. There’s space for them to be models.

TB: Definitely. That can really be a shift. I think we have examples within our faith communities of those who have been antagonistic to mental health and those who have been promoters. Some faith leaders, unfortunately, have discouraged mental health treatment by saying, “If you prayed about it, you should be fine” or, “You don’t need to go to outsiders; we have enough with our faith.”

I know that that has been very harmful, with people who needed help either not seeking it or those who sought it having shame or embarrassment, thinking their faith must be insufficient.

We also have wonderful folks across denominations who have promoted these messages of compassion and care and collaboration. I really appreciate a number of pastors who now have referral lists and provide pastoral support and possibilities in the community for mental health services as well.

F&L: So it is not necessary for every church to have a counselor on staff, but every church can provide resources and entry points.

TB: Absolutely. Depending on the mental health professional you’re talking to, sometimes it is preferable for them not to be a member. Because if someone is a member, they would have to have very clear boundaries, or Sunday worship can turn into crisis response for the mental health professional who is coming there to worship. That would just have to be clear.

F&L: What would your advice be to a pastor who wants to be a good model or provide resources? What could be a starting point for a church that recognizes this need but might be stretched thin?

TB: One resource is Mental Health Ministries. They have a number of ready-made resources that deal with this integration of faith and mental health. In addition, I would say integrating mental health in the liturgy. So when you’re having prayer, include those who are facing depression, those who are living with anxiety, those who are struggling with addiction, those who are grieving.

When you have health fairs at the church, be intentional about making sure there’s a table for mental health. Not only do we have screenings for blood pressure and everything else, but if you just contact a local agency or the National Alliance on Mental Illness, they have a number of volunteers who in most areas would be willing to come out for health fairs or as speakers. Do not feel like you have to know everything about every disorder. Collaborate with experts.

The other real starting place, I would say, is to find out if in your congregation there are any licensed professionals. If you have therapists, social workers, psychologists, then if you all have a part of the service for announcements, they could do a mental health minute once a month or once a quarter. During those announcements, they could come up and just give some tips about mental health.

If you are still printing physical bulletins, you could include some resources in there or some quick facts about mental health. In your sermons, I would say think about trauma-informed sermons, which is really just being biblically based. There are many stories in there of trauma, of abuse, of despair.

Sometimes, we go into what I call a psychological prosperity gospel — “If you love Jesus, you’ll be happy all the time.” It’s just not accurate. It was not true for David. It was not true for the disciples or the prophets. It wasn’t true for Jesus. It’s important for us to really pay attention to the ways psychology shows up in the text that will allow our ministry and our preaching to be more relevant to where people are in their lives.

When we have these various retreats and conferences, if we have a youth conference, think about having a workshop that has to do with mental health. Many of our youth are really struggling. Yes, it’s important for them to know the Bible; we also want them to live. We see rates around suicide and other challenges, and so we need to be holistic in our planning of our retreats and conferences so it is spiritual, emotional and physical health all being encouraged as the will of God for people’s lives.

F&L: You had a wonderful quote in a prior interview: “To require people to only feel joy and gratitude is dehumanizing. It does not give space or permission to honor their humanity.” I’m wondering what you might say to that balance we’re all trying to strike between honoring the trauma and keeping ourselves going.

TB: Holding space for both and leaning more into the ways that we can honor time for our stillness and healing. I think many of us cope by busyness, and that gets celebrated in our communities, because you’re giving back and you’re volunteering for everything the church needs. Sometimes, we’re not tuned in to the person who is doing a million things — what may be going on on the inside of them that is motivating that. Can they tolerate stillness and silence?

Pay attention to the different warning signs of how the effects show up. It can show up with depression. It can show up with irritability. It can show up with anxiety. It can show up with numbness.

If you’re seeing all these things happening and you feel nothing, that’s also a trauma response, and so being compassionate with ourselves as we take note of that and then being mindful of our healing practice like, “What do I do for my wellness?” That can include our journaling. It can include talking with family and friends, but also I hope people will consider therapy as well. Often, we just try to stuff it down and say, “I prayed about it; I’m over it.” But it still bleeds out in different areas of our lives.

I would highlight the commandment that we love others the way we love ourselves. We often focus on the others — “Do unto others as you would have them do unto you.” We focus outward, but if I am to love you as I love me, then I have to also love me.

Does the way that I give myself permission to rest look like love? Does what I choose to feed my body look like love? If I loved myself, would I set some boundaries I’m not currently setting? Love ourselves and lean into some of the stillness so that we can really heal.

On a Friday night in 2019, the Rev. Dr. LaTonya McIver Penny miscarried. Less than 48 hours later, still bleeding and in pain — and without a word to her congregation about what she’d endured — she led the Sunday morning service at New Mount Zion Baptist Church in Roxboro, North Carolina, just as she had every week for the previous five years.

She now acknowledges that that should’ve been a sign, but she had been full-throttle for so long that it would take a devastating pandemic and a doctor’s stern warning to even entertain the idea of slowing down.

“I’m supposed to keep pushing and pushing, right?” said Penny, who reluctantly took four weeks of medical leave before resigning as senior pastor in fall 2021. “We’re not superhumans, but we don’t know that, because we don’t want to let anyone down. But the pandemic made me stop and pay attention.”

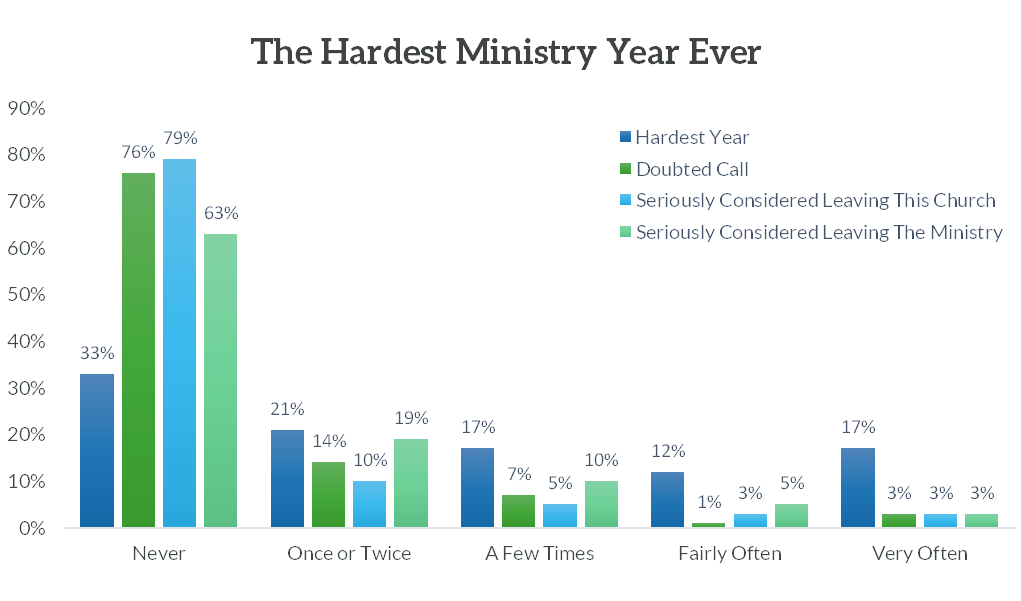

She wasn’t alone. According to surveys conducted last summer by the Hartford Institute for Religion Research at Hartford International University, 37% of clergy had “seriously considered leaving pastoral ministry” at least once during the preceding year, and 67% had thought at least once during that time that it was the hardest year of their ministry experience. Likewise, Barna Group, a research firm that focuses on religion, found in fall 2021 that 38% of pastors had considered quitting full-time ministry within the past year, up 9 percentage points from January 2021.

Those numbers fed speculation that the pandemic might be fueling a “great resignation” for clergy. But Scott Thumma, the director of the Hartford Institute for Religion Research, doesn’t see evidence of a mass exodus.

Thumma noted that 5% of the clergy who responded to the institute’s survey in summer 2021 had thought about leaving the ministry “fairly often,” while another 3% had done so “very often.”

“The 8% who said ‘fairly often’ or ‘very often’ — that’s not insignificant. If 8% of clergy truly did leave, you’d notice,” he said, estimating that to translate to at least 40,000 pastors.

“But it’s also definitely not almost 40%,” he said, referencing the Barna study.

Most of the pastors who expressed serious frustration with their circumstances were already in difficult situations with struggling congregations before the pandemic ushered in controversies over in-person worship, mask wearing and vaccine policies, Thumma said. Racial tensions in the wake of George Floyd’s 2020 murder and political divisions associated in that year’s presidential election exacerbated those challenges; nevertheless, 63% of respondents indicated they’d never once considered leaving the ministry, he added.

Thumma and his team will continue tracking the pandemic’s effect on faith communities in a multiyear study — Exploring the Pandemic Impact on Congregations — funded by a grant from Lilly Endowment Inc. On the basis of the data he’s gathered so far and conversations he’s had with clergy, Thumma said he anticipates that more pastors will ultimately re-imagine how they do ministry rather than walk away from the profession altogether.

“The pandemic was the hurricane or the tornado, and we’re just now coming out of the basement … and seeing the devastation there. Now, the real work happens of putting things back together, of learning how to be church,” he said.

What are signs in your ministry and your life that you have ignored but need to attend to?

On the other side of the storm, Thumma said, “You could say, ‘Screw this; I’m going somewhere else.’ Or, ‘What plan do we want for our town? What are the things we didn’t like about it before that we don’t want to repeat? How do we reshape what church looks like? After the storm, how are we going to re-create the world?’”

For Penny, that started with a basic question: “What now?” She’d been the single mother of toddler twins when she walked away from her career as a public school teacher to pursue a divinity degree at Wake Forest University.

Inspired in part by challenges her children faced as preemies, she’d founded a nonprofit disability advocacy group called Mary’s Grace before graduating in 2013. She’d go on to build her ministry around inclusion and radical hospitality, making that the focus of her 2019 doctoral thesis while simultaneously serving as the first female senior pastor at New Mount Zion Baptist Church and continuing to run her nonprofit.

She was also putting in 12-hour days serving victims of domestic violence in her position as executive director of Family Abuse Services of Alamance County. The arrival of COVID-19 only heightened her pace as she juggled virtual services, her children’s educational needs, and the rising demands of both her congregation and those she served in the community.

By the time her congregation returned to in-person worship in September 2021, migraines, chest pain and stomach upset were a regular part of Penny’s day. Being back in the sanctuary “felt suffocating,” she said. Her doctor told her that something had to give.

In reevaluating her call, Penny said, she realized that the heart of her ministry had never relied on the physical church. She’d spent years teaching faith communities how to be more inclusive of those with disabilities or others who might not feel comfortable walking into a sanctuary.

Almost immediately, she and her husband, also a minister, founded Belonging Fellowship, a virtual church that emphasizes inclusivity. Because the church is online and there’s very little overhead, money raised by the congregation has fulfilled wish lists for residents of group homes, stocked the classrooms of first-year teachers, and helped families pay their rent and fill their gas tanks, Penny said.

Are there areas of ministry, congregational life or community connection that you recognize need reshaping or re-creating? What would it take to do that?

She also made a list of her “nonnegotiables.” After Floyd’s murder, she and her staff at the domestic violence shelter had published a statement affirming the lives of Black people — only to have a white board chairman order her to take it down.

Penny would not take a position, she decided, “where I have to fight for my Blackness.” She committed to spending more time with her children and invested in self-care, like exercise, eating right and saying “no” unapologetically.

In February, feeling healthier than she had in a long time, she became the executive director of the Laughing Gull Foundation, which supports grassroots efforts toward LGBTQ+ equality, higher education in prison, and climate and environmental justice.

“This has been what my soul needed. I matter on the other side of this,” said Penny, noting that she’s not doing less but rather more on her own terms.

“I think pastors are so busy praying for other people that they forget to pray and ask God, ‘What are you calling me to do?’” she said. “Just because you’re called into ministry doesn’t mean you’re called into the same space forever.”

‘Church shouldn’t hurt’

Like Penny, the Rev. Riana Shaw Robinson was exhausted long before the pandemic hit. The mother of four was still nursing her youngest — twins — while earning her seminary degree and serving as associate pastor of formation at Oakland City Church, a multiethnic faith community.

The only Black woman on the senior leadership team, Robinson organized the church’s first anti-racism conference and started a racial justice small group. Every time a high-profile case of violence against Black people made the news, Robinson felt responsible for processing it with her congregation.

“I felt I was responsible for all the people of color at the church. I needed to show up for them, be available for them, listen to them, be a safe space for them — and be responsible for teaching a bunch of white folks,” she said. “I’d hold all of that for so long, and then I’d come home and cry by myself.”

In March 2020, just as the pandemic hit, Robinson attended a three-day retreat sponsored by Liberated Together, an organization dedicated to empowering Christian women of color doing justice work in typically white, patriarchal spaces.

“I was already operating under the expectation that so many women of color operate under: ‘You will save all of us,’” she said. “They put me back together — me Riana, not me the pastor. We listened each other into life. What if that’s what church did? What if women of color showed up and said, ‘I’m so tired’ and the first thing people say is, ‘We believe you’?”

Following Floyd’s murder, Robinson said, she resisted requests from her church to lead its response “to give it legitimacy,” instead choosing a leave of absence, self-care and more time with her children. She still loved her congregation, but in September 2020, she let them know that some of her work, particularly on the racial justice front, was starting to feel “extractive.”

They asked for another year of service from her; she gave them 10 months, then, “feeling reduced to dust,” set off on a solo trip to Spain in July 2021 “to sit in old churches and weep and release.”

There had been so much noise over the previous 15 months, Robinson said, that she’d struggled to hear God’s voice. She briefly considered abandoning ministry altogether, but her “accountability group,” the women in Liberated Together, urged her to reconsider. She was still a pastor, they said, even if she didn’t ascribe to the white, patriarchal model of invincibility. “Where,” they asked, “do you feel freest to be honest?”

Robinson read Austin Channing Brown’s “I’m Still Here: Black Dignity in a World Made for Whiteness” and recited Psalm 23, subbing in female pronouns. She began working with women and gender-nonbinary people of color through the Faith & Justice Network and attending a Black congregation, a restorative measure she described as “like going to your grandma’s house.”

Are extra areas of responsibility placed on your ministry because of who you are? What are your expectations of yourself in that regard? Are there boundaries you can set?

“Church work is always hard. Ministry is always hard. I just don’t want it to be hard because I have to translate or explain myself or explain how I feel,” she said.

“Church shouldn’t hurt. What if church is where women of color show up and more isn’t demanded of them? They’re just seen and blessed in community and beloved?”

To that end, Robinson is launching a worship community “that unapologetically serves the needs of women of color, period,” she said. She envisions a bricks-and-mortar church with a virtual component for accessibility and hopes to have it up and running by Advent.

“It’s been a really painful year and a really beautiful year, where I feel like God has held me without demanding anything from me,” Robinson said. “I feel like God has been so gracious and gentle, saying, ‘I’m still with you.’”

‘A call is a dynamic thing’

The Rev. Anna Tew concedes that she was among the 3% of clergy who responded to the Hartford survey last summer by saying she’d considered leaving ministry “very often” the previous year. It wasn’t her congregation that made her feel that way, said Tew, the pastor at Our Savior’s Lutheran Church in South Hadley, Massachusetts, since 2016.

Instead, she said, her exhaustion “was an over-time thing.” She felt obligated to be at her desk eight hours per day, had fallen into a pattern of working on her days off, and was following social media accounts that made her feel guilty if she didn’t view “every little work task as a blessing,” she said. As a queer millennial, she was also doing a fair amount of “cultural commuting” within a largely straight, baby boomer faith community.

“I don’t think congregations get better than this, so if I’m not happy here, I might not be happy anywhere,” Tew thought. “That did lead me to really look at, ‘Do I really want to do this? Do I think it’s still worth doing?’”

Tew went on sabbatical in the summer of 2021, engaging in what she calls “the great unfollowing,” muting colleagues that made her feel guilty about wanting some downtime and “finding more clergypeople who had a healthier view of work and boundaries.”

She read Nedra Glover Tawwab’s “Set Boundaries, Find Peace: A Guide to Reclaiming Yourself,” calling it a “life-changer, career-saver,” and spent more time with nonchurch friends who modeled a healthy work-life balance.

“I didn’t know how to ask for what I needed — ‘Please don’t speak to me that way as a pastor’ or, ‘I’m not available right now; can we talk tomorrow?’” she said.

Which responsibilities drain you? Where are your models for a healthy work-life balance?

Tew also earned her CrossFit Level 1 certification and became a personal trainer. She noticed that when she received text messages from her training clients, she didn’t have that same tightness in her chest as when her congregation reached out. Perhaps, she thought, if she stopped treating every pastoral concern as if it were an emergency, she could better appreciate the pieces of the job she loved: the flexible schedule, the personal connections, “creating community around doing hard things” and following Jesus.

“I don’t think I would have done all that re-imagining without a crisis of international proportions,” said Tew, who notes that responding honestly to the survey question was the first step to acknowledging that she needed to approach ministry differently. “This is where I feel called right now, and I’m still careful not to hold it too tight. This is right now. Reevaluating our call is really important — a call is a dynamic thing.”

‘Something different’

By the time the pandemic struck, Ryan Timpte had been a children’s minister for almost 20 years, the last decade at Lafayette-Orinda Presbyterian Church in Lafayette, California, an 1,800-member congregation with “staggering” resources, he said. Pre-pandemic, the children’s programming ran parallel with adult worship services. When they moved online, he hoped the worship structure would pivot to appeal to the youngest members of the congregation, perhaps using “kid language” to explain how to pass the peace virtually or including some lessons on “why we do what we do.”

Instead, he said, the focus was on replicating what adults at LOPC had been used to.

“The pandemic could’ve been an incredible opportunity to open worship up, make it new. Instead, it was all about [keeping] the adults engaged and plugged in.” he said. “I am sure congregants enjoyed logging on and feeling just a little bit of what their normal had been. It’s just that their normal had cut kids out.”

His church wasn’t the only one to adopt that model, he said. Timpte maintained contact with a group of colleagues who had, individually, come up with creative ways to keep children engaged but had done so largely independent of any support from the decision-making bodies at their churches. With more demands for pastoral care and other church resources, Timpte said, he understood why children’s ministries were not the first priority.

“But it’s just one more way in which the church reflects society,” he said. “Children’s ministry is a lonely thing even in the best of times, and the pandemic was not the best of times. With all the resources I had, I still couldn’t change the system. And if I couldn’t do it there, I couldn’t do it anywhere.”

In fall 2021, his wife was offered a job leading university and young adult ministry at a Presbyterian church in Berkeley. Timpte said it felt like the right time to leave, not just his church, but church-based ministry. He committed to being a full-time dad to their two young sons, ages 7 and 3.

Then a new opportunity opened up. A member of LOPC who had volunteered with the children’s ministry when his own kids were little was launching a startup toy company dedicated to following sustainable practices, educating kids about the environment and keeping plastic out of the ocean. Would Timpte like to join as creative director?

“I’m committed to making the world a better place for children, and for 20 years, I thought that was through the church. Now, I think it’s maybe something different,” he said, noting that his calling hasn’t changed, just where he uses it. “There’s a whole other way to make the world a better place.”

How has the pandemic affected your sense of call or where you might serve it? What could that look like?

‘Hope and redemptive purpose’

In an article published by Christianity Today in February, the Rev. Peter Chin acknowledged that he was considering leaving the ministry after 20 years. His Methodist congregation, Rainier Avenue Church in Seattle, had survived the “run-and-gun” style of the early days of the pandemic. But entering the second year, disagreements over masks and vaccines mounted, and relationships among the traditionally tight staff began to fray, injecting “a paralyzing degree of complexity and controversy” into every decision he made, he wrote.

“Even in the best of times, pastoral ministry has always felt like a broad and heavy calling,” he wrote. “But the events of the past few years have made it a crushing one.”

The response he got from colleagues let him know he was not alone. Each had felt crushed at times by the pressures of the pandemic, but no one seemed to have any great advice on how to handle them.

“Everyone was in the middle of this torrent, swimming at the same time,” Chin said.

Also, no one could believe he’d acknowledged his concerns so publicly in his essay.

“The unanimity of the response was, ‘I feel seen, I feel heard, but I don’t feel I can say these things, because I don’t know how it’s going to come off with other people,’” Chin said. “A lot of the struggle for pastors is this cultural expectation that pastors don’t feel this, because they’ve got a higher calling. But it’s healing to say it and to put it out there and be free from the secrecy of it.”

In May, Chin credited that honesty with leading him to a better place. He said he’s spoken truthfully with his congregation about the stress and grief associated with this time, as well as how God’s love for him — and the expectation that he will love others — has served as an anchor. He’s also openly addressed staff conflicts, leaving no room for gossip or misunderstandings.

“Honesty has really panned out for us,” Chin said. “We need to go beyond creating the illusion that everything is fine, and truth-tell.”

Much of what has drained pastors predates the pandemic, he said. But the pandemic has quickened the pace. Rather than viewing this as destructive, why not view it as corrective, a chance to shed traditions that weren’t working and embrace new practices that sustain pastors and their congregations?

“This is an opportunity for us to re-imagine and reclaim some things about the church,” Chin said. “In God’s community, there’s hope and redemptive purpose for even the hardest things.”

Questions to consider

- What are signs in your ministry and your life that you have ignored but need to attend to?

- Are there areas of ministry, congregational life or community connection that you recognize need reshaping or re-creating? What would it take to do that?

- Are extra areas of responsibility placed on your ministry because of who you are? What are your expectations of yourself in that regard? Are there boundaries you can set?

- Which responsibilities drain you? Where are your models for a healthy work-life balance?

- How has the pandemic affected your sense of call or where you might serve it? What could that look like?