Shouldn’t we get it by now?

From the inside looking out, we’re aware of the dimming daylight even as we’re typing away, chasing children, on another Zoom. And then we check the time: only 5:15. Whoa.

We’ve observed “spring forward, fall back” our whole lives. We’ve made it through our share of winters. We understand the shortening of days and lengthening of nights. We know how this works. Don’t we?

And yet here we are, year after year, still surprised, still looking outside and saying, “Can you believe how dark it is already?!” (Or, in the words of a TikTok I still think about, “Bro, it’s 5:15! What?”)

When we think of Advent, the themes of darkness, expectation and (im)patient anticipation often come to mind. ’Tis the season to watch and wait. But there’s another element of this time of year that I want to dwell in: the element of surprise.

When we’ve grown up in the church, or even when we’ve simply attended for long enough to know the lyrics and liturgies, the story of Christianity can become a little too familiar. For us and for our salvation he came down from heaven, we may find ourselves droning along each Sunday, focused more on our lunch plans or what remains to be accomplished before Monday’s return. We may grow so accustomed to the mysteries of our faith that we throw around terms like “incarnation” and “ascension” in a way that strips them of any mystical meaning.

But can we back up just a few steps?

[He] was incarnate from the Holy Spirit and the Virgin Mary

and was made truly human.

Think about how you’d “translate” this into normal, everyday language. God chose to be like us, putting on our flesh forever. That’s a crazy, crazy story.

For our sake he was crucified under Pontius Pilate;

he suffered death and was buried.

On the third day he rose again.

No wonder the early Christians got some weird looks (and, well, worse).

“Historically, [Christianity] was a surprise because Christianity was born and emerged and grew in a Roman world that had no expectations for it, didn’t know what it was, and couldn’t have anticipated it,” says C. Kavin Rowe, a New Testament scholar. “Christianity was something that the Roman world had never seen and didn’t even have categories for.

“Christianity was surprising also in its particulars,” he adds. “It introduced patterns of life into the world that caught people by surprise in a good way.”

It’s safe to say that at this point in history, Christianity — at least in the way most people conceive of it — is not much of a surprise. It’s pretty mainstream: no longer a fringe movement. But just dream with me for a second. What if the good news — in all of its particulars — became surprising once more? What if we were as astonished by it as by evening’s early arrival?

Yes, there can be plenty of comfort in familiar rhythms and words, but what might it look like to reclaim some of that wonder — not just for shock value, not just because we’re bored or distracted, but in a way that honors the story we have received?

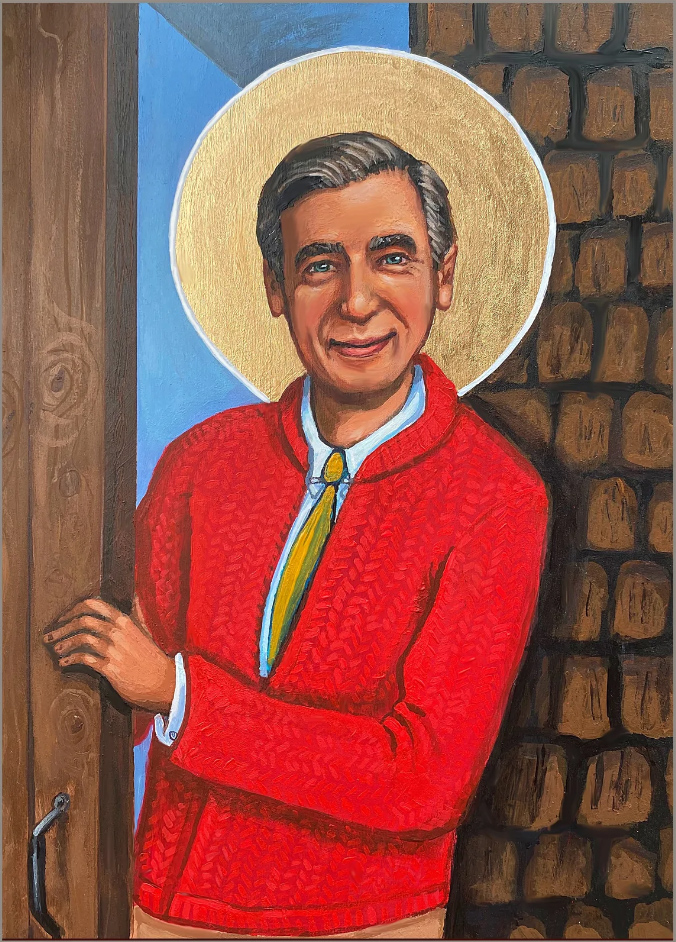

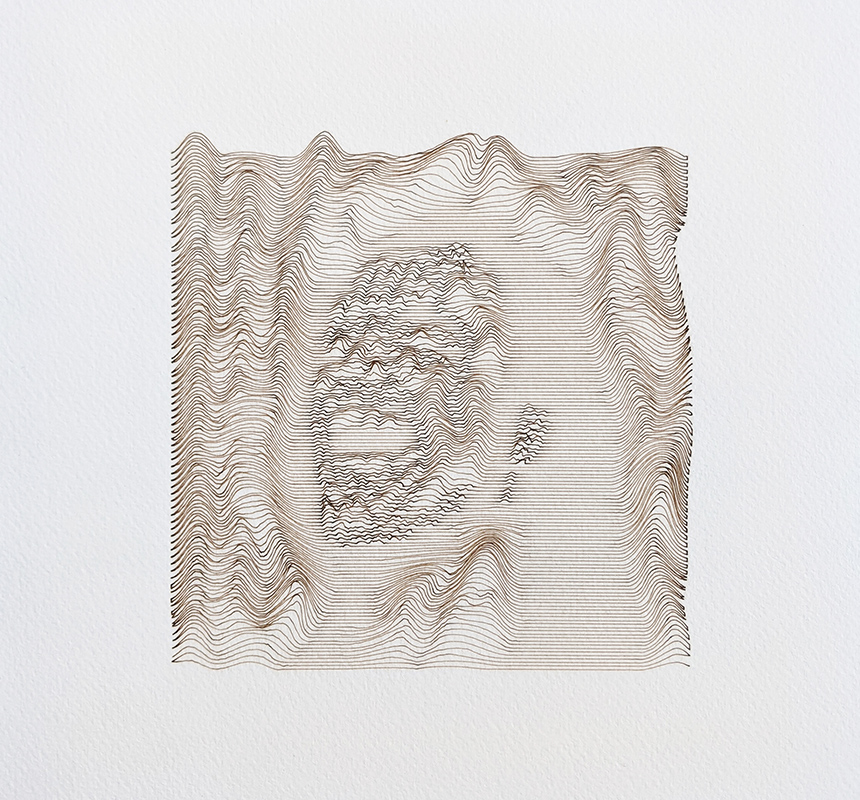

Maybe it’s as small as reading the passages we know by heart in a new translation for a few days. Maybe it’s looking them up in the Art Search from the Calvin Institute of Christian Worship and seeing some of the creativity those passages inspire. Or maybe it’s simply changing the posture we take when we approach the old, old stories.

How might we be caught off guard?

We joke about the changing seasons surprising us, but the brief days and long nights still startle us each year — “How is it dark already?!” “The sun is already up!”

I hope the jarring reset of our clocks and microwaves and (non-smart) watches might nudge us to do a bit of an internal reset too. I hope the changing church seasons might surprise us as well— that, in some weird and wonderful ways, we might be amazed this Advent by the bizarre, glorious truth of the baby who was God-with-us, the God-man who sits at the right hand of the Father, still wearing his human skin and bearing marks of Roman nails.

I hope we never get used to it.

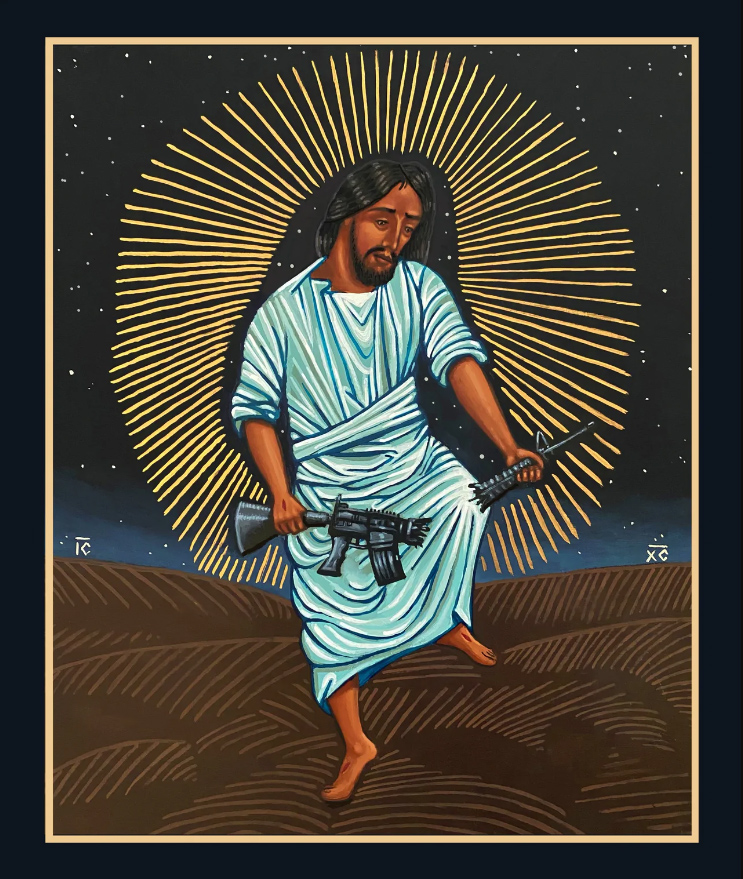

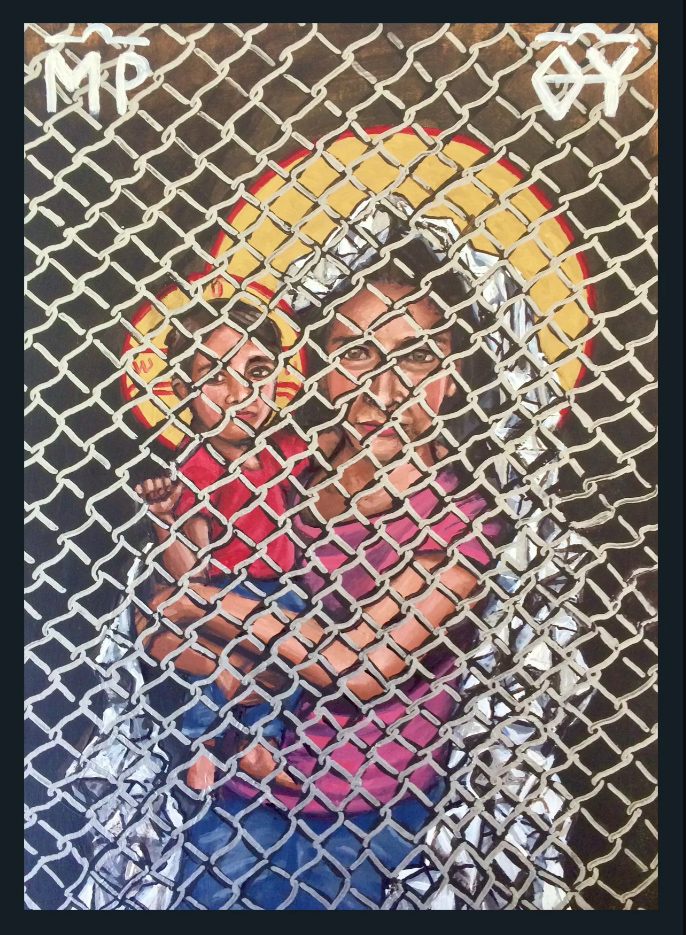

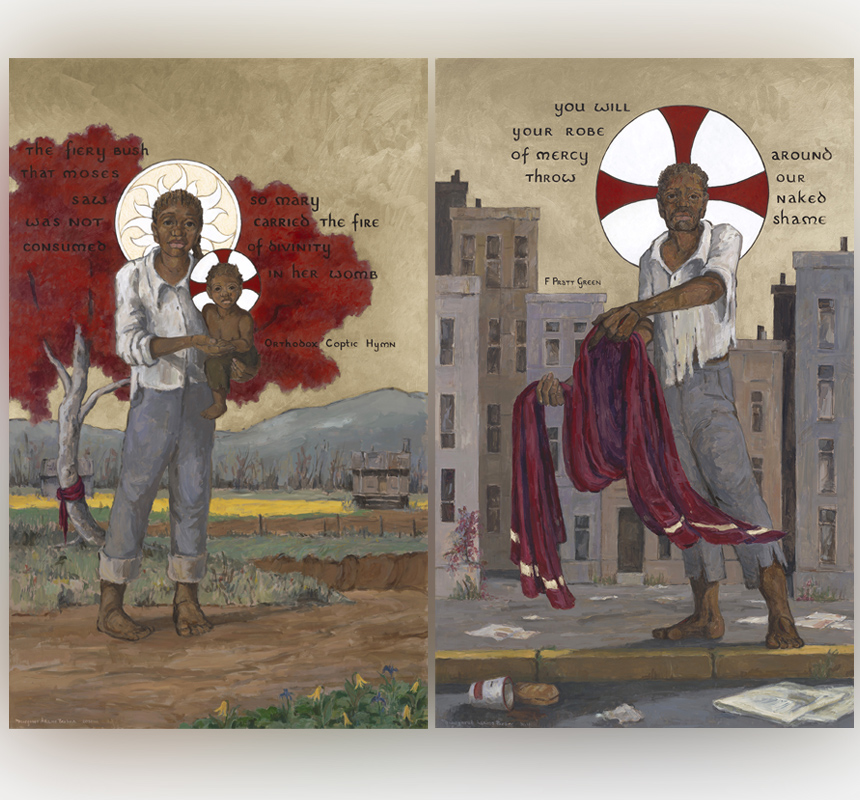

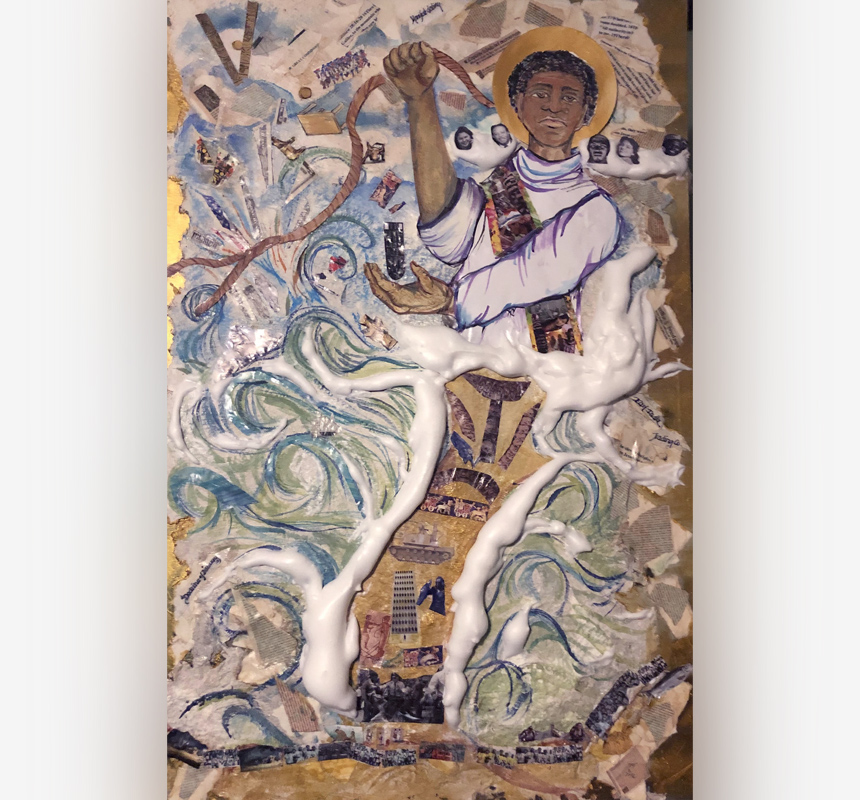

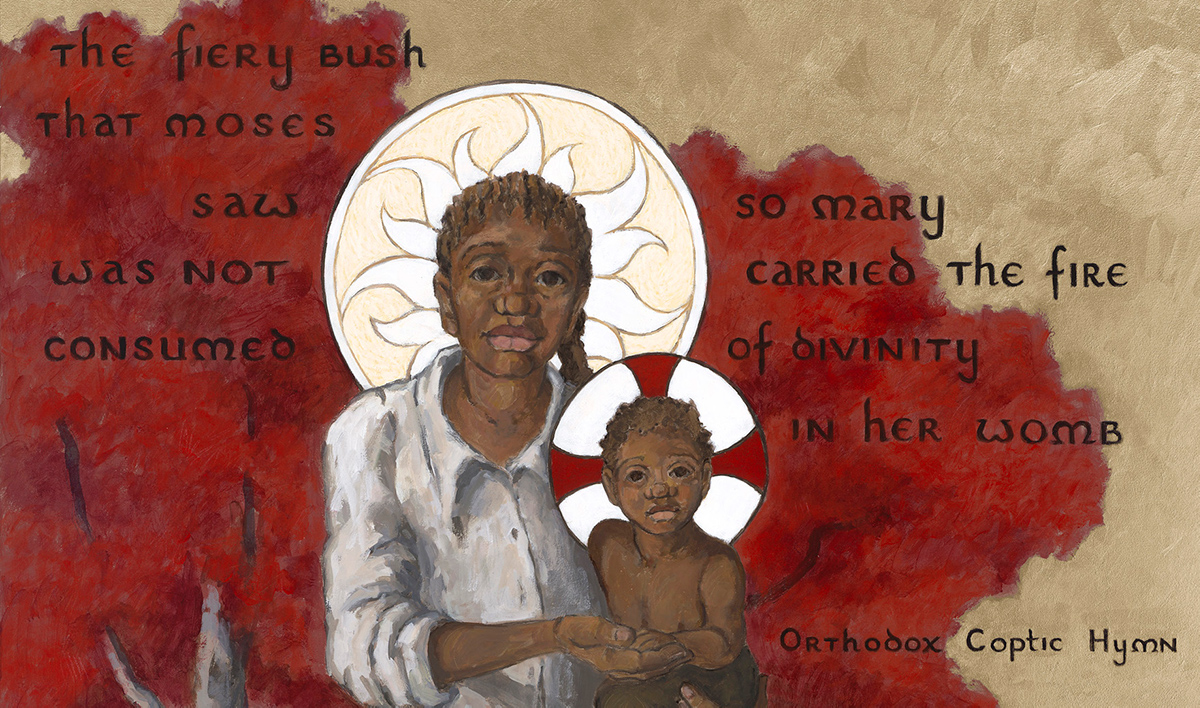

Kelly Latimore is a St. Louis-based artist who specializes in painting icons. Some of his images have attracted widespread attention, as when he faced death threats over “Mama,” his Pieta-style image of a Black Mary cradling the body of Jesus, who resembles George Floyd. Others depict figures such as Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Pauli Murray and Mahalia Jackson. One, “La Sagrada Familia,” shows the holy family as modern immigrants walking in the desert.

Latimore spoke to Faith & Leadership’s Aleta Payne about his work. The following is edited for length and clarity.

Faith & Leadership: Can you talk about how iconography grew out of your collective work for connectedness as a member of a monastic community?

Kelly Latimore: I’m a PK, a pastor’s kid, and I grew up in a small Protestant denomination. It was very much about transcendence. Later in life, after graduating [from college], I ended up in Athens, Ohio, and was a part of this small monastic farming community. The main mission of that place was growing vegetables and food for food pantries. Volunteers would come to the farm and help in that work, but also people who were poor and living in shelters, coming and joining us in that work as well.

Putting your hands in the soil and weeding a bed of carrots across from a complete stranger, and the conversations that came out of that — I really learned that the way we use things in the world is of spiritual significance. It was a transition away from transcendence. It was more about engaging God in a physical incarnation in the world.

It was less about transcendence and more about engagement, embodiment and communion, connection. And so it was a very profound time. The first icon that I painted was called “Christ: Consider the Lilies,” and that stemmed out of my relationship with my best friend, Paul. We used to talk about a lot as we were growing food: How do we as farmers have a right relationship with the earth, and how do we, as Jesus would say, consider the lilies of the field? What does that mean?

I had done a lot of traditional icons; I started how all iconographers start, going over these old images and tracing them as best I could. But then when I got to a point where I wanted to try my first original icon, it was that idea of “Christ: Consider the Lilies,” and it focused on our common work. And what was interesting — it wasn’t a great first. It was a good first try. Christ, if you see it, he’s almost surprised that the lilies are in his hands, and the lines are shaky.

But what was interesting about it, and I think what was beautiful, was that the community embraced it, because it was a part of our common experience. It showed me how art can be a focal point for focusing and seeing in a new way how we want to live in the world. As time’s gone on, this has been the theme of the work that my partner, Evie, and I collaborate on.

Trying to find the holy family that is among us here and now or Christ that is in our own neighborhood, and bringing these modern images of people that are struggling or in pain right in front of us but inherently have the image of God within them: the refugee, the immigrant, those in prison, those suffering from living in tent cities.

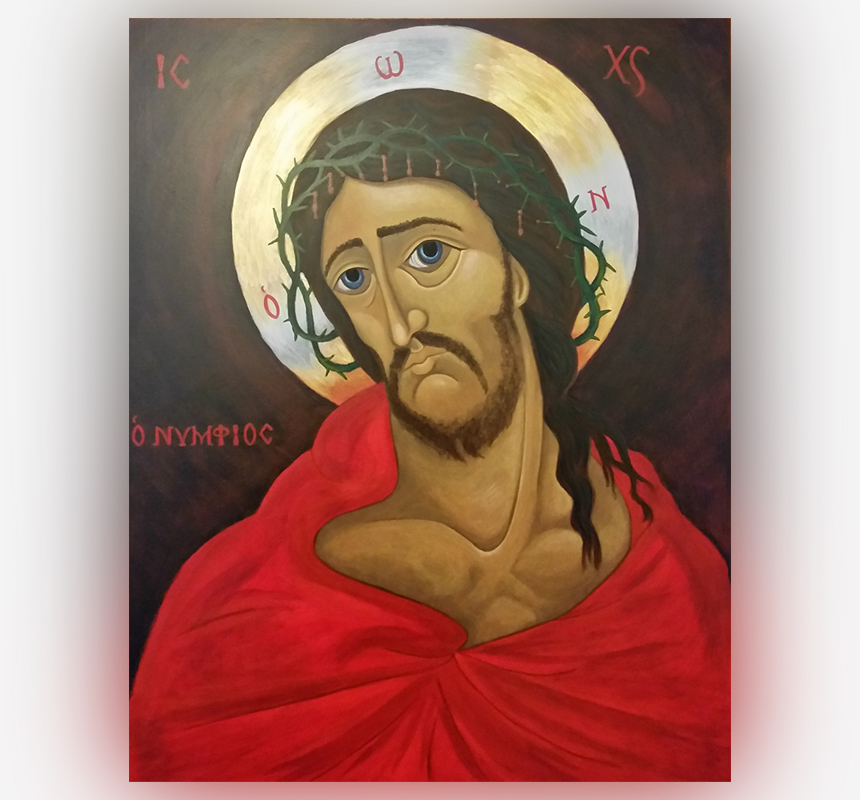

There’s another icon I did called “Cloud of Unknowing.” In my early days in iconography, I had started an icon called “Christ the Pantocrator” or “Christ the Teacher,” which is a pretty traditional icon where Christ is holding the Gospels and holding a blessing hand. I got really frustrated. His face was fine, but his hands weren’t right. And I ended up putting it up on a shelf, where it sat for two years.

And then at one point I had gotten some new gold leaf in, and I was looking for something to try it on, and I found that icon and was like, “Ah, I didn’t really like this anyway,” so I just started gold-leafing over it. But I realized that because I had reworked that icon so much, the paint stood up, even with the gold leaf [over it]. It looked like a gold leaf board, but if you got up close, you saw the raised face of Christ.

I had two priests that are friends of mine, and I was showing them what I was working on, and they saw it and both said at the same time, “That’s ‘The Cloud of Unknowing.’”

The 14th-century work is about [our] potential for knowledge, or knowing God — that the more we put God under a cloud of unknowing, or a cloud of forgetting, the closer we’ll be to God through our hearts and through our experience.

My friends, those priests, named what that image was, and therefore it became a new gift. I think that’s what art can do for us in our communities. It should teach us how to see in new ways, not only to show how similar we are, but also [to name] the racism that might be within me or to name the ways that I’m not loving my neighbor well or other ways that maybe I’m not seeing God as clearly in my neighbor and around me.

An artist’s life is to be more present. For my partner, Evie, and I — and Evie is a big part of the work — we’re just trying to be present to what is going on around us. But for me, all of this artwork doesn’t really mean much without the relationships that make life worth living. And I think that’s so beautiful about iconography; it’s a very communal art.

As an artist, I’m entering into this improvisation or this dialogue, which I think doesn’t happen in a lot of artists’ work. Working on this artwork with churches can be very hard. But what is so gratifying and is a gift to me is that part of the work: the communality, the conversations about images that mean something to them and that want to push them toward communities and push them toward new ways of being in the world and new ways of relating to one another. I wouldn’t be able to enter into that if I wasn’t doing specifically this work, and so I think it’s just about receiving those gifts and doing the best I can to translate that gift [of communality] into the work.

We are just constantly inundated with images. What happens, especially with the social media world, TikTok, Instagram, whatever, is that we can be so quick to speak into something. I hope my art has this potential to teach us to not speak into something but just to learn how to observe, to be still and observe something. And that’s my hope for these images, that they can potentially create dialogue. Not only an internal dialogue but also a dialogue between each other. And that just observing and not speaking into something, I think, is the first part of connecting to the piece of art, whether it’s art in churches, in this iconography or elsewhere.

What is our church art for? Is it glorified wallpaper, or can it be something that can help us see each other, see in new ways and see God in new ways?

When I was young, Jesus greeted me every day at my grandmother’s house.

A framed print of Warner E. Sallman’s “Head of Christ” graced the wall adjacent to her front door. Jesus looked like an elegant surfer dude to me — tanned, with honey-streaked brown hair and blue eyes that gazed benevolently to the heavens.

The Almighty didn’t look anything like me, but so what? It certainly didn’t make me question my faith or my self-worth, because my religious experience was steeped in the tradition of the African Methodist Episcopal Church.

From the all-Black choir that sang the songs of Zion to the Black mothers of the church who prayed over me to the Black pastor who preached that, yes, Jesus loved my little chocolate self, my Blackness was continually validated. At my grandmother’s, I was more concerned about her yelling at me for slamming the screen door than I was about the white Jesus hanging next to it.

But once I became aware of the world and my place in it, I realized that imagery was a powerful tool through which white supremacy operated. Whiteness has always been the default for defining everything America deems worthy: standards of beauty, true patriotism, innovators and intellectuals and stewards of power. Even our most sacrosanct attribute — spirituality — demands that we pray to a God presented as white.

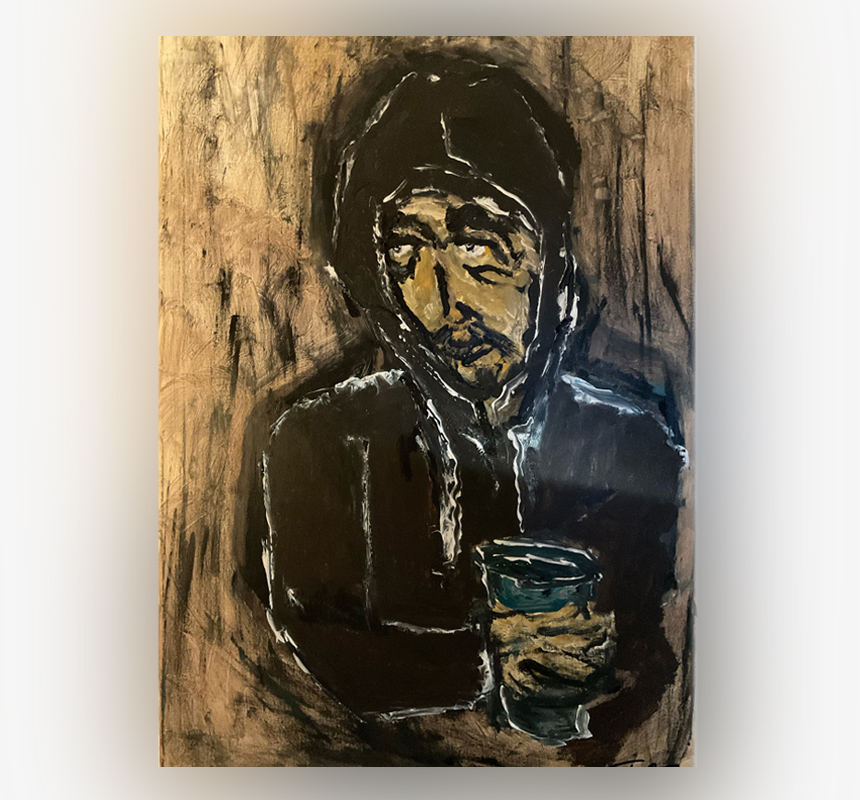

That’s why “DeColonizing Christ,” a visual arts exhibit that runs through Dec. 19 in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, is so fascinating. It dares to imagine Jesus Christ as what he was, a person of color. It dares to debunk everything we’ve been programmed to believe about Christ’s appearance while interpreting a historical fact.

As the exhibit draws to a close well into the season of Advent, it has offered opportunities for those who have never deeply questioned their vision of Christ to reconsider the frame through which they have been looking.

What images of Jesus did you grow up with, and how do they align with your vision of Christ now?

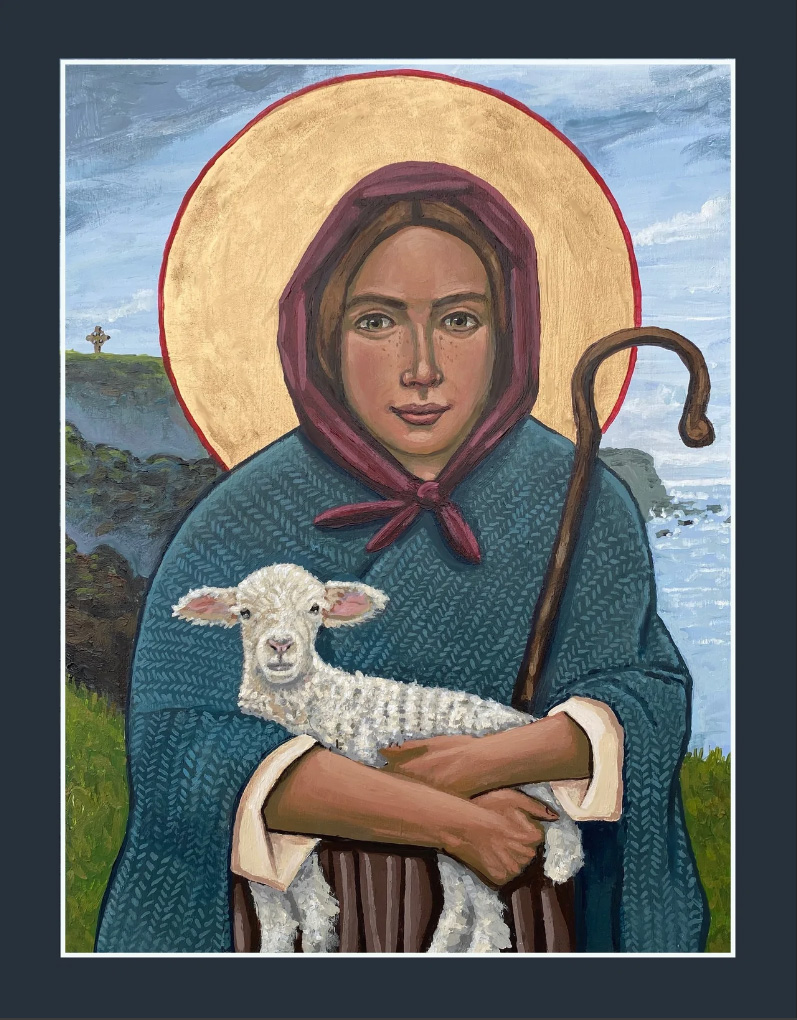

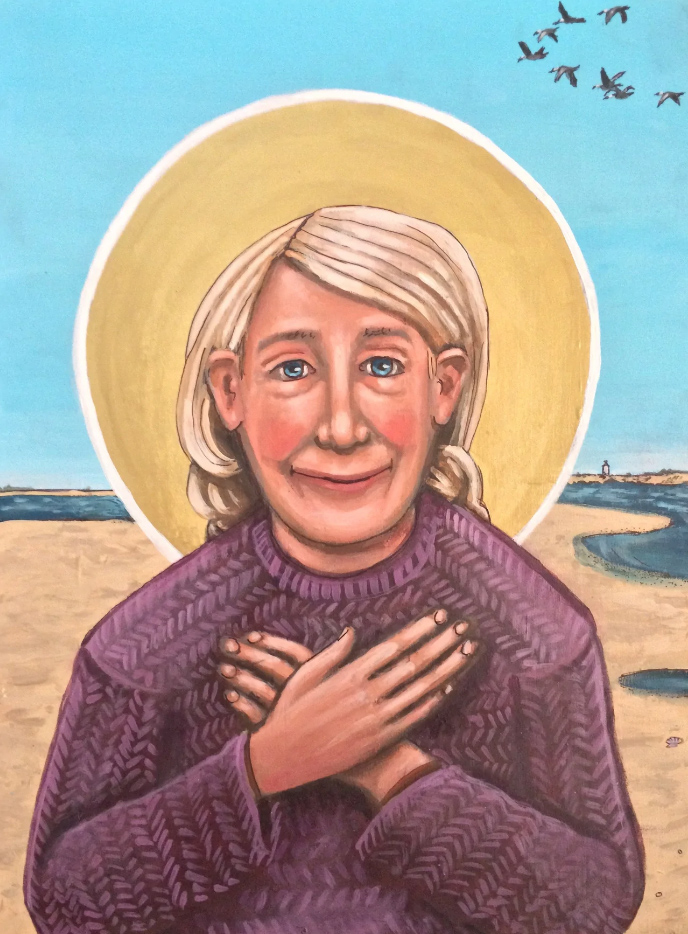

Some of the exhibit’s artists took license to envision Christ as a woman, a Latino child, or a brother on the street sporting a halo-shaped afro and smoking a blunt. Each of the 40 pieces invites the viewer to imagine Christ as more provocative and edgy than the sanitized version we’re used to seeing.

“There are some people that will deny [that Christ was not white],” said Matt Parsley, of Harrisburg. “But I consider it to be a fact.”

On a recent Sunday, Parsley, who is white, viewed the exhibit with friends Helena Felix and Tracy Cisney. “In the long term, this exhibit could have an impact,” he said. “That’s the whole point of art, is to challenge your way of thinking.”

For the Very Rev. Dr. Amy D. Welin, the dean of St. Stephen’s Episcopal Cathedral, where the exhibit is displayed, it’s not a stretch to think of Christ as someone other than white and ethereal.

“Christ was edgy, and he hung around with edgy people,” Welin said. “We’ve so emasculated Christ that he’s like our pet gerbil. He’s not threatening — he’s nice. He’s the Good Shepherd. But we also see in the Bible that he’s kicking ass in the temple; he’s turning over tables. So he was good, but he wasn’t nice.”

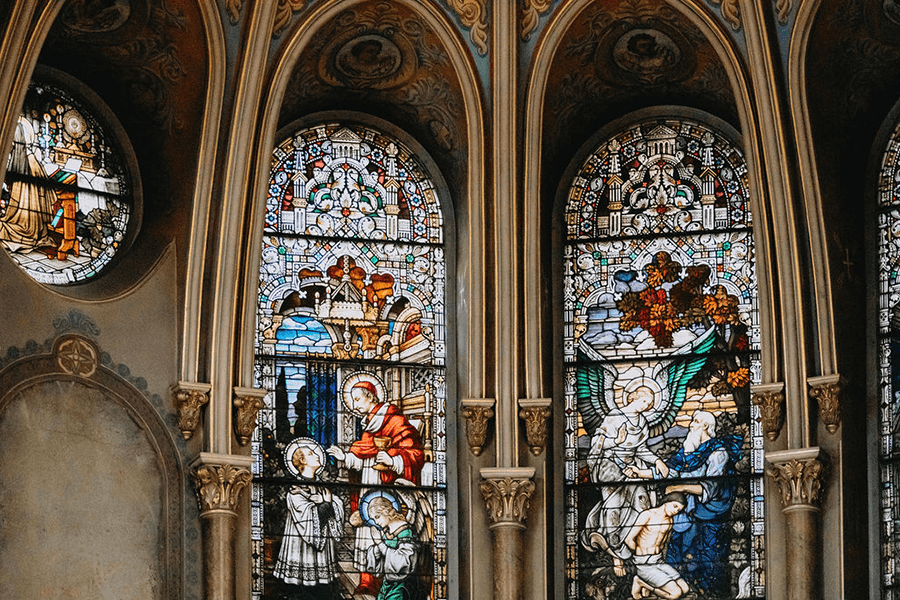

We are in St. Stephen’s, strolling through the sanctuary, an immaculately reverent space that welcomed an average of 150 congregants every Sunday before COVID-19 hit. The images of “DeColonizing Christ” are juxtaposed with the stained-glass images of Bible characters, all depicted as white, that line either side of the cathedral. Taken together, the disparate images create an interesting theological debate.

“We all enculturate Jesus. Every tribe. We all paint him as one of us, which is fine, because we want to be close to God, and that’s what people do,” Welin said.

If any of these images challenges you, why do you think that is?

“But then we learn that the images of Jesus were used to silence and oppress people in Latin America and Indigenous people and the enslaved in the United States. So there’s this fine line that says we want Christ to be one of us … but we don’t want him to be one of you.”

The narrative of Jesus being “one of us” was normalized through commercialization of Sallman’s “Head of Christ” painting, the one that hung in my grandmother’s house. It has been described as the “best-known American artwork of the 20th century.”

Sallman, a religious painter and illustrator from Chicago, styled the painting to appeal to 1940s American Protestant audiences, and it was soon printed on prayer cards and circulated by all denominations, regardless of race. The image, which has been reprinted more than 1 billion times, defined the nation’s religious culture, creating another white default that most Christians took for granted.

“I always thought Christ looked like one of my people,” said Welin, a self-described pale-skinned Irish American. “I went to a Catholic high school, and the images we had in textbooks and religious art were of a Jesus who was definitely European.”

It wasn’t until she was well into her 30s that the revelation hit her: according to the Bible, Christ was a Palestinian Jew. Even as a medieval history major, Welin was never taught that. Years later, after Trayvon Martin was murdered, she started to consider how white supremacy manifests itself in ways big and small. It wasn’t lost on her that public outcry had forced the removal of certain public monuments and other symbols of the nation’s racist past. Meanwhile, every Sunday, the stained-glass images in her own church stared at her almost mockingly.

“It became really clear that the image of Christ had been commercialized and promulgated,” Welin said.

How could your congregation explore the enculturated history of Christianity as part of formation and worship?

Last year, a parishioner told Welin that if she really was serious about doing the work of diversity and inclusion, she need look no further than her own sanctuary. “Because all of the iconography in the cathedral says this is a white space,” he told her.

“And I was like, ‘Wow, we need to broaden our palette. This is an opportunity,’” the priest said.

Welin met with staffers at the Art Association of Harrisburg to brainstorm about the concept. One of them pointed out that it seemed the theme of the exhibition should be decolonizing the image of Christ.

“And that’s how we got our title,” Welin said.

She enlisted the Rev. Mack Granderson, the pastor of Crossroads Christian Ministries Church, also in Harrisburg, to chair the selection committee. A music major from Philadelphia who for years owned a jazz club in Harrisburg before going into ministry, Granderson was well-qualified to lead the project. In the ’80s, he served for seven years under then-Gov. Richard Thornburgh on the Pennsylvania Council on the Arts.

The committee reached out to artists, universities and arts organizations in New York, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Delaware and Washington, D.C. They secured a grant from the Arts for All partnership, a collaboration between the Cultural Enrichment Fund and the Greater Harrisburg Foundation.

In all, the show features 28 original artworks, plus a dozen on loan from private collections. Although the images are unquestionably thought-provoking and confront racism in diverse interpretations, there is a troubling omission. All but seven of the 17 participating artists are white, and two out of three cash prizes awarded in the juried exhibition went to white artists. Michael Reyes, a Franciscan friar and trained artist from the Philippines, won the People’s Choice award for his work “Christ the Dreamer.”

If some of the most-praised works in an exhibit that seeks to challenge white supremacy are created by white artists, and if lived experience is the biggest informer of personal expression, what does that mean for the exhibit?

It’s a question that gets to the heart of the complicated nature of racism, intended or not. The novelist Toni Morrison once noted that she worked hard to write without the intrusive “white gaze,” the idea that Black writers must explain cultural references to white readers, must hand-hold and make them feel comfortable.

How does the art in your church reflect your congregation’s beliefs?

Lori Sweet, of Harrisburg, award winner of the Bishops’ Prize for her work “The Healer,” admitted that she hesitated to enter a piece in the show because her previous religious works focused more on the feminine and nature. Portraying Christ as a person of color didn’t fall into her wheelhouse, in part because she is white.

“I did feel like, ‘Who am I to represent this, because this isn’t my experience,’” said Sweet, who has a background in social work. “But it’s been part of my life’s work to stand up and be present for people who are oppressed and suffering and bear witness to that. So I feel honored and grateful that I can stand in solidarity with others on this issue — and it’s continuing to inform me.”

“The Healer” features an olive-skinned, hooded-robed Jesus. He has a direct gaze and full lips, holding a lamb that represents “not a sacrifice but the true and authentic part of who we are, the delicate and vulnerable part,” Sweet said.

“I think when people look at each other, they’re seeing the outward appearance,” she said. “And I guess I see Christ as being able to look beyond the surface and being able to see the sacred in each of us, and that is healing.”

In your church’s context, what gaze is missing? How might it be valuable to include that perspective? How might you invite it in an authentic and respectful way?

Best in show went to “Pantocrator in Black and Brown” by Brian Behm of North Carolina.

For Granderson, who is Black, the lack of participants of color was disappointing, though understandable. His years serving on the Pennsylvania Council on the Arts taught him that recognition for artists of color, getting their works displayed in galleries and museums, has been an ongoing struggle.

“But then something came to mind,” Granderson said. “I was very excited for white artists, because they would have to go through something internally to create an image of Christ from Palestine. There will also be a reckoning that must take place with the person who is seeing the exhibit. I would hope that kind of conversation, even if it’s an internal conversation, must take place.”

Not surprisingly, countercultural images similar to those in the exhibit have drawn controversy. St. Louis artist Kelly Latimore’s “Mama,” depicting a Black Virgin Mary cradling Jesus’ body after his crucifixion — with Jesus portrayed as George Floyd — was recently discovered to be missing from a public exhibition of Catholic University of America’s Columbus Law School. Officials at the school replaced it with a smaller version.

Latimore, meanwhile, has faced death threats.

“I think, unfortunately, racism is part of a lot of it, especially death threats [that include] derogatory remarks about George Floyd specifically,” Latimore told Religion News Service, adding that some of the threats took issue with any depiction of Jesus as Black.

“Really white supremacist, racist stuff — which, theologically, is what racism is: a complete denial of the incarnation of Christ,” he said.

It may be that breaking down the barriers of systemic racism starts incrementally, with art exhibits like these. “DeColonizing Christ” not only dares to see Jesus differently but does so with none of the mean-spirited bickering that sullies our public discourse today. In their introspection, exhibitgoers may see themselves differently, too.

With that in mind, Welin is giving serious consideration to hosting rotating exhibits that feature different points of view at her church. “I really like the idea of using our cathedral as an art gallery, because then we could expand our spiritual life,” she said.

Harrisburg’s diversity — Pennsylvania’s capital city is 51% Black — demands that inclusivity be addressed. How to build community within the walls of the church is something Welin is still thinking about.

“This has been a local event,” she said. “It is wonderful that this has generated conversation in other churches about the use of art to illuminate matters of social justice. So perhaps the generative outcome is an opportunity to inspire other communities of faith to consider what they can do locally to address issues of justice. Because just like politics, justice is usually a local thing.”

As I sat in the sanctuary talking to Welin, it occurred to me that the exhibit was doing exactly what it was designed for — encouraging conversations that allow for expanding our worldview.

The God I know would be pleased.

“We can’t make up for 1,000 years of oppression,” Welin said, “but we can start to do things differently. And this is a start.”

How might different visions of Jesus broaden conversation in your church and community?

Questions to consider

- What images of Jesus did you grow up with, and how do they align with your vision of Christ now?

- If any of these images challenges you, why do you think that is?

- How could your congregation explore the enculturated history of Christianity as part of formation and worship?

- How does the art in your church reflect your congregation’s beliefs?

- In your church’s context, what gaze is missing? How might it be valuable to include that perspective? How might you invite it in an authentic and respectful way?

- How might different visions of Jesus broaden conversation in your church and community?

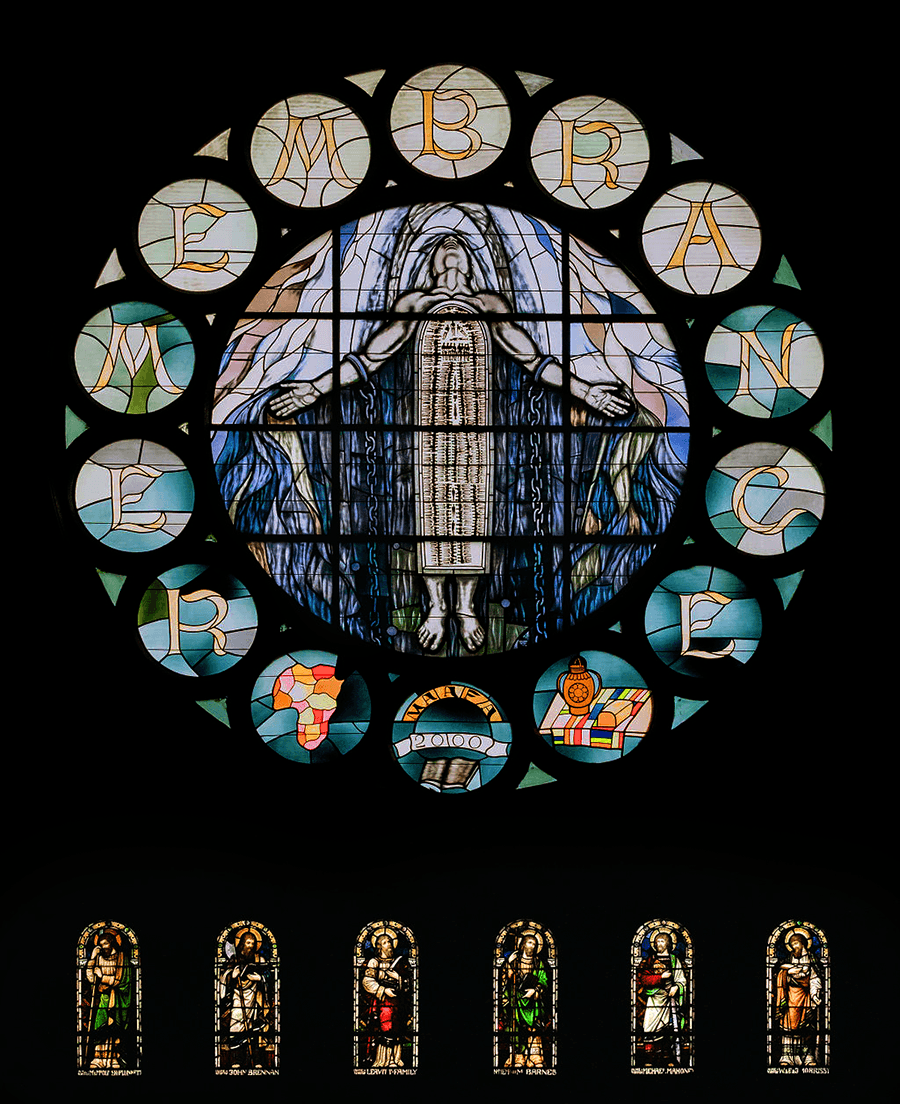

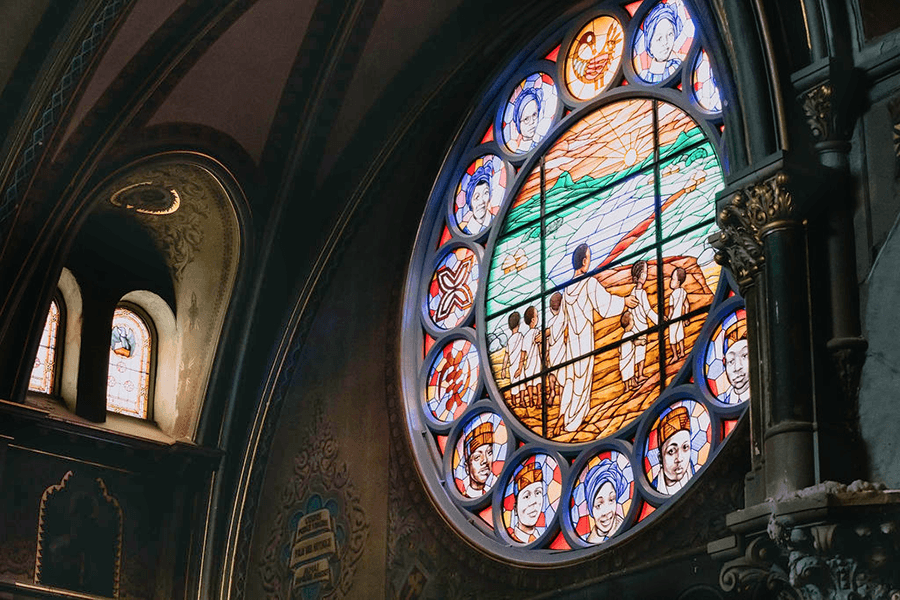

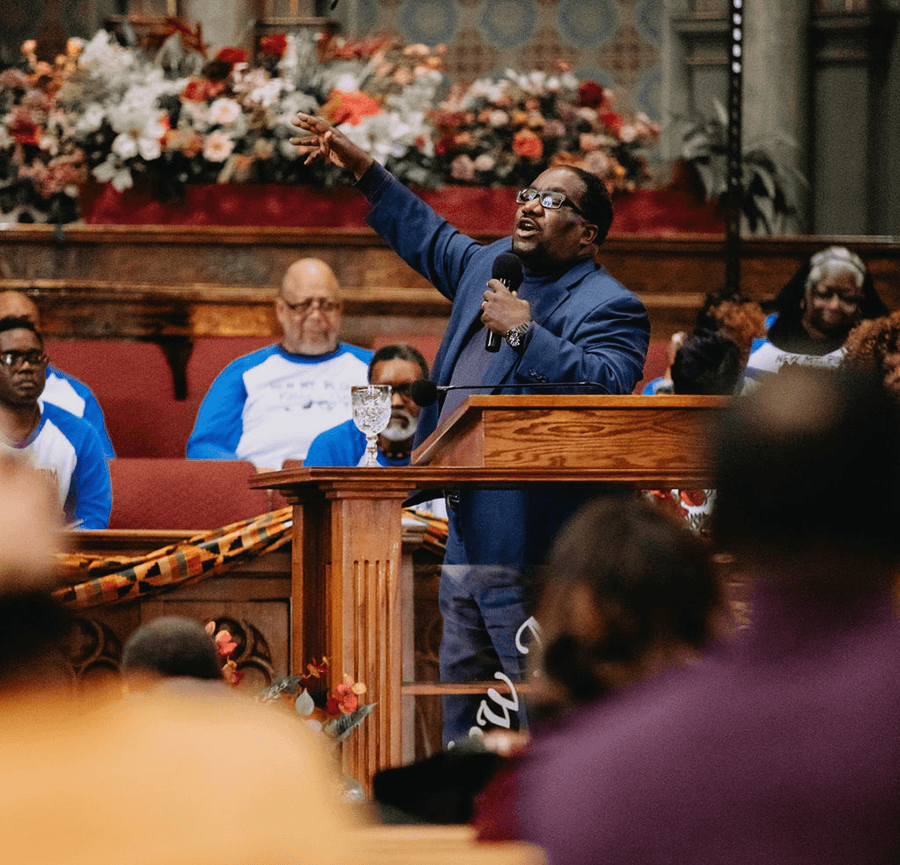

The praise dancers, dressed in black, moved in a sea of color, surrounded by the jewel tones of the sanctuary’s rose windows and the parishioners’ attire. In a space now shared with their ancestors, the girls embodied the strength and resilience they had inherited, their choreographed movements amplifying the message of a song from the movie “Harriet.”

“I’m gonna stand up, take my people with me … I hear freedom calling, calling me to answer.”

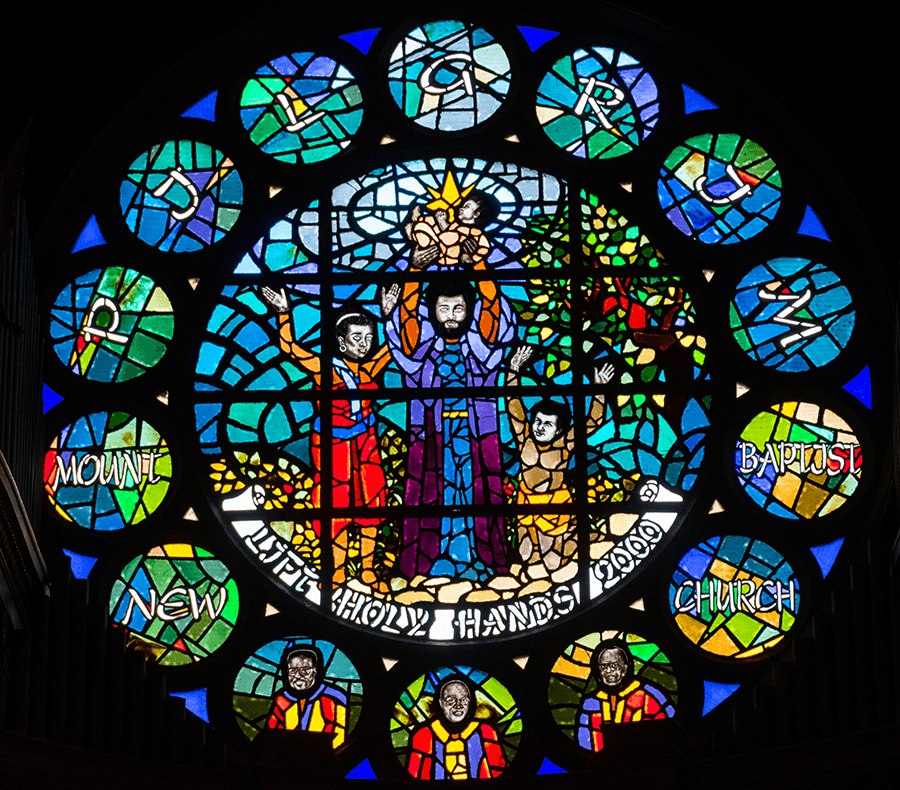

Members of Chicago’s New Mount Pilgrim Missionary Baptist Church, where the young women danced, are well-practiced in telling their story through art. That includes the trio of 25-foot rose windows, through which the church has embraced the tradition of stained glass as a teaching tool while depicting the unexpected.

What kinds of art — visual, musical, dramatic, etc. — tell the story of your institution?

The Maafa Remembrance, North Star and Sankofa Peace windows capture narratives from the past and present. In this season when the Christian church celebrates resurrection, the people of New Mount Pilgrim visibly honor both pain and promise through them in ways that are heartbreaking, breathtaking and unavoidable.

“To be spiritually healthy, a person has to have a healthy sense of remembrance,” said the Rev. Dr. Marshall Hatch Sr., the church’s pastor.

To celebrate the Lord’s Supper is “to remember the places where we have fallen and been lifted, the suffering and sacrifice it has taken,” Hatch said. “We often deal with the abolition of slavery movement and liberation for black people from bondage in America and the way the exodus or the Passover story undergirds the Lord’s Supper.

“We’re part of a continuum of that liberation narrative of God.”

Taken together, the trinity of windows represents many things to New Mount Pilgrim: the claiming of the worship space as their own, the fuller representation of narratives too often ignored by broader culture, and a willingness to confront unimaginable grief by putting it at their spiritual center.

How does your church or organization “honor both pain and promise” in its history and future? In what ways does it take part in the “continuation of the liberation narrative of God”?

In the Maafa Remembrance window, the Christ figure’s outstretched arms are shackled and his face turned upward. The sacrificed one is an African man whose body is depicted as a slave ship. Each of the figures within it is a human being, confined while being transported across the Atlantic.

“Maafa” is a Swahili word meaning great disaster or calamity, and the word “remembrance” encircles the window’s center, melding the suffering of millions during the middle passage with the passion of Christ.

The North Star window represents the great migration of African Americans leaving the American South in the first half of the 20th century. It also commemorates the congregation’s story, with images of its three longest-serving pastors.

The Sankofa Peace window, the most recent addition, takes its name from a word of the Akan people of Ghana meaning “go back and retrieve it.” It memorializes young African Americans killed by violence during the civil rights movement and, more recently, in Chicago neighborhoods. At the same time, it offers a vision of restoration — a dark-skinned Jesus leading children to green pastures and still waters lined with thatched-roof homes.

“It’s about the journey back to reclaiming the value of the village, which is the way we see the Bible,” Hatch said. “More than art, though, it has driven our community ministry [with a vision of] hospitality, family, extended family, mutual support, the centrality of children and the elders, and people in the margins being brought to the center.”

How are the “values of your village” visible or made clear to everyone who walks into your work or home space? How might this clarity enhance hospitality, outreach or stewardship ministries?

New Mount Pilgrim, which has 1,200 members on the rolls, belongs to the American Baptist Churches in the U.S.A. and the Progressive National Baptist Convention. For almost three decades now, members have been transforming the sanctuary — previously home to an Irish Catholic congregation, before redlining and white flight flipped the neighborhood’s demographics — into a space that reflects the ethnicity of its present flock.

When they purchased the building in 1993, they acquired with it years of deferred maintenance. The rose windows in place at that time were buckling, and the congregation had two options: repair them with the existing fair-skinned depictions of Jesus, Mary and other models of faith or create their own stained-glass art reflecting the current congregation’s heritage.

“We had the trilogy in mind 20 years ago, not knowing it would take that long,” Hatch said.

As the members set out to make the sanctuary their own, church leaders found new homes for the existing rose windows. The congregation also raised $35,000 from the sale of a marble altar and used those funds for the roof and other exterior work. They sold two statues to a convent for an additional $8,000 for repairs.

In the late 1990s, Hatch was on sabbatical at Harvard Divinity School when he came across an art book by Tom Feelings, an African American artist from New York, about the transport of African slaves across the Atlantic to the New World. The images in “The Middle Passage” had a deep effect on Hatch, and his congregation would eventually choose one of them for the Maafa window.

Feelings attended New Mount Pilgrim’s 50th anniversary celebration in 2000, at which the window installation was dedicated, and he was so moved by the power of such an image in a church that he refused the money the church had offered him for its use, Hatch said.

“We became friends after that,” he said. When Feelings died in 2003, Hatch delivered his eulogy.

The schematic of the slave ship Brookes that Feelings incorporated into his art originated with the British abolitionists. In a history of that movement, one of the activists is said to have noted that it never failed to evoke horror.

Centuries later, New Mount Pilgrim’s window is thought to be the largest representation of the slave ship diagram in the world, according to Cheryl Finley, an art historian and the author of “Committed to Memory: The Art of the Slave Ship Icon,” which traces the use of the icon from abolitionist posters to more-recent visual arts and pop culture.

What is it your institution needs to remember in order to be healthy? What grief needs to be confronted or lifted up? Who has been excluded from your institution’s prominent story, based on race, class, gender or sexual orientation?

Finley writes: “Undoubtedly, the crucifixion offers a compelling parallel, for both images have been repeatedly rendered and reworked over the centuries, but they simultaneously embody death and rebirth. The slave ship … is a site of death, of dying Africans, and of new life, of a people who would persevere in the face of slavery and unspeakable cruelty to become a free people who helped define the modern era.”

The Rev. Marshall Hatch Jr., the executive director of the Maafa Redemption Project, a ministry of the church, wrote his master of divinity thesis on the Maafa window. It is a communal symbol, he said, for people who have experienced “the crucifixion of black people in America” through not only slavery but also Jim Crow, mass incarceration, police violence and other oppression.

“It’s iconic in that it’s a relationship between the art and the congregation that produced it,” he said. “It invites constant reflection and wrestling over time.”

The North Star window, also completed 20 years ago, bears witness to the journeys of millions of African Americans in the early to mid-20th century who moved to urban areas in the North and West seeking economic opportunity and safety. That history includes the Hatch family’s ancestors, as well as longtime New Mount Pilgrim pastor the Rev. James McCoy, who came to Chicago from the same Mississippi town as Hatch Sr.’s father.

At the North Star window’s center is a scene inspired by the 1970s Alex Haley book and related TV miniseries “Roots,” with the ritual of an African father lifting his newborn child to the heavens and saying, “Behold, the only thing greater than yourself!” The New Mount Pilgrim congregation sees a similar moment embodied in its baby blessings as the infant to be blessed is lifted by the pastor.

“That’s the true north of any community, … the lifting up of the next generation as its hope,” Hatch Jr. said.

After the first two rose windows were replaced and the necessary maintenance completed, the third window was allowed to remain as clear glass with a sun film for the next 19 years.

Planning for the Sankofa Peace window began in late 2016. New Mount Pilgrim’s youth chose five young people killed by violence in Chicago to be represented in the window, alongside the four girls killed in the 1963 bombing of 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama. At the times of their deaths, the youth in the window ranged in age from 11 to 17. They are depicted in African garb, surrounding an image of Jesus.

The North Star window speaks to the Sankofa window, Hatch Jr. said, calling the people to create policies that lift children up and prevent violence and tragedy.

“It’s a call to action … to recreate, reconceive, reimagine beloved community,” he said. “It’s the Sankofa window that imagines the day after resurrection.”

Among those in the window the congregation remembers as martyrs is one of its own. Demetrius Griffin Jr., who was christened and baptized at New Mount Pilgrim, was murdered in 2016 not far from the church. He was 15.

Rochelle Sykes, his aunt, also grew up in the congregation and is now on staff. She said his death is agonizing for the family — many of whom are part of the congregation — and the community. To have a family member die “at someone else’s hands — it’s like something has been snatched from you,” she said, looking up from a pew between the Maafa and Sankofa windows. “Sitting in this sanctuary, sometimes it just eases that pain, it eases that ‘Why?’”

Sykes was present when the Sankofa window was installed. It gives her hope to offer children and youth the experience she had of feeling embraced by the congregation, “showing you how God loves you and how to spread that love to others.”

Though Griffin’s murder remains unsolved, that of 17-year-old Laquan McDonald, another of the window’s youth, led to the controversial prosecution and conviction of the Chicago police officer who fatally shot him in 2014. Jason Van Dyke was sentenced in 2019 to less than seven years in prison. Several youth connected to the congregation knew McDonald and asked for his image to be in the window, church leaders said.

Yet McDonald’s death had power far beyond those who knew him, explained the Rev. Stephen G. Ray Jr., the president of Chicago Theological Seminary and of the Society for the Study of Black Religion. Because a Chicago police officer shot McDonald 16 times, and because of the city government’s efforts to cover up Van Dyke’s actions, Ray said, the murder resonates with the vulnerability that young black people feel, faced with structures of white power and violence.

“He then becomes a martyr to all black lives that are lost for no other reason than because they were black,” Ray said. In the context of the larger window, this is the way the community expresses and passes along to future generations that “the lives of all of our children are sacred,” he said.

For all three windows, the church collaborated with Botti Studio of Architectural Arts, a company that has worked on high-profile projects such as St. Patrick’s Cathedral in Manhattan. Botti Studio designers helped New Mount Pilgrim leaders adapt images they had in mind and translate them into stained glass.

The church raised more than $110,000 in donations from within and outside the congregation for the final window. It was dedicated in 2019, the 400th anniversary of the first African enslaved people’s reaching the English colony of Virginia.

In New Mount Pilgrim’s sanctuary, the newer art lifting up black life and the resilience of black people stands in contrast to the preexisting stained-glass windows and murals closer to the floor, which depict Jesus, saints and others as European in appearance. For the church’s black congregants, appreciating such devotional art requires an ability learned growing up in a white supremacist society, Ray said.

“Part of what the system of white supremacy does is it gives black people the capacity to see the humanity of white people even if that’s not reciprocated,” he said.

As a result, black people can look at white depictions of Jesus, the apostles and other models of faith and see through the white skin to the humanity, he said. Black Christians don’t make a one-to-one correspondence between a fair-skinned Jesus and the real Jesus. In contrast, many white Christians have simply looked at ancient models of faith depicted with European features “like a stylized photograph,” he said.

The rose windows are set in a building that also still reflects its white, Roman Catholic history. Do you think this contrast would be disruptive or constructive for worshippers? What contrasts do you experience as you worship or work?

These tensions exist across the country, especially with respect to the role and function of stained glass, Ray said. Since the great migration, there has been a national phenomenon in black church life of sacred spaces, both synagogues and churches, not having been built by the black congregations, he said.

Some Afrocentric congregations, such as Trinity United Church of Christ on the South Side of Chicago, constructed their own buildings rather than worship with religious art created by European congregations.

Though the transformation of New Mount Pilgrim’s sanctuary is incomplete, the messages of the rose windows resound in the space.

Robert Ervin, a deacon, said that when he looks at the windows, “it humbles you seeing where you came from and all we’ve been through.”

Ervin noted that the bird’s head in the Sankofa window is turned around and reaching toward its back, symbolizing that “we have to look to the past and glean from it in order to move forward.”

Questions to consider

Questions to Consider

- The members of New Mount Pilgrim Missionary Baptist Church are “long-practiced with telling their story through art.” What kinds of art — visual, musical, dramatic, etc.– tell the story of your institution?

- How does your church or organization “honor both pain and promise” in its history and future? In what ways does it take part in the “continuation of the liberation narrative of God”?

- How are the “values of your village” visible or made clear to everyone who walks into your work or home space? How might this clarity enhance hospitality, outreach or stewardship ministries?

- What is it your institution needs to remember in order to be healthy? What grief needs to be confronted or lifted up? Who has been excluded from your institution’s prominent story, based on race, class, gender or sexual orientation?

- The rose windows are set in a building that also still reflects its white, Roman Catholic history. Do you think this contrast would be disruptive or constructive for worshippers? What contrasts do you experience as you worship or work?