For almost a decade, I’ve enthusiastically followed Streetlights’ journey as the organization’s innovative Latino leaders re-imagined the audio Bible, infusing it with the vitality of hip-hop beats and showcasing diverse and authentic voices. Their artistic vision and dedication to placed-at-risk youth speaks directly to my heart.

Born from a vision in a basement 17 years ago, Streetlights has grown into a thriving nonprofit with an $800,000 annual operating budget, 75,000 newsletter subscribers and 430,000 app users worldwide, according to its leadership. It has achieved international influence, reaching 18 million plays of its audio Bible — currently in Spanish and English — with plans for more languages. Beyond the audio Bible, its initiatives also include the Corner Talk teaching video ministry and a music ministry through its touring band, ALERT312.

How Streetlights expanded from basement dream to international reality offers a powerful learning opportunity for us all, including for my own role as an executive director. Since visiting the Streetlights studio in Chicago’s Belmont Cragin community last fall, I’ve gleaned valuable lessons in organizational leadership and capacity building from its inspiring story of collaboration.

Esteban Shedd, Streetlights’ co-executive director, said his vision emerged from the disconnect many youth in his community felt toward the Bible. They found it inaccessible — difficult to understand and hard to relate to culturally — with a lack of engaging resources. Shedd, inspired by the scripture “So then faith comes by hearing, and hearing by the word of God” (Romans 10:17 NKJV), envisioned a culturally relevant, bilingual audio Bible for the digital-native generation. That led to the development of artistically rich digital tools that engage young people from urban communities in their heart language.

Shedd patiently refined his vision over two years, supported by prayer, discussions with leaders and family, and in-depth research about resource production. He waited for the right moment — confirmed by the Spirit and community support — balancing the demands for action with the wisdom to nurture the vision, anticipating when peace and faith would align.

The catalyst came from a friend at GRIP Outreach for Youth, a faith-based nonprofit working with Chicago’s young people, who suggested that Shedd speak with that organization’s executive director. This conversation ignited Streetlights’ inception, leading to a series of conversations and careful planning with GRIP’s board. Bolstered by their support, including covering his salary for a month, Shedd was offered precious time and space. GRIP evolved into an incubator for Streetlights.

But, Shedd said, it was a challenging decision for some in GRIP’s leadership, given that GRIP, too, works with urban youth in underresourced neighborhoods. The initial wariness that the partnership might strain GRIP’s limited budget eased after a board member highlighted how Shedd’s culturally relevant Bible project aligned with GRIP’s mission, offering new ways to serve youth.

Shedd said those who were hesitating realized that the organizations’ missions weren’t separate but an opportunity for unity; they came to see GRIP as part of a larger, interconnected ecosystem. Strategic planning for the partnership began, focused on communicating clearly and engaging stakeholders, crafting a framework that equipped GRIP to effectively navigate and adapt in this new role.

This was also a leap of faith for Shedd. Newly married and juggling his roles as rapper and hip-hop group leader, he committed to Streetlights despite the economic uncertainty for his family. Through prayerful consideration, he and his wife found peace, understanding that vision and conviction are crucial in Christian leadership and may precede funding. Trusting in God’s call and in GRIP’s leadership, Shedd entered into a mutually affirming partnership, where he knew that his vision would be honored, with no attempts to change, control or compete against it.

GRIP’s support meant more than guidance — the executive director and board offered spiritual backing, mentorship, friendship and essential connections for the work ahead. Shedd vividly remembers Scott Grzesiak, GRIP’s founder and then-executive director, providing unwavering encouragement during uncertain times, which was vital to persevering.

In that crucial first month, Shedd devoted countless hours to developing Streetlights’ business plan, capturing its vision and how it would fit within GRIP’s fiscal umbrella. Thanks to the supportive environment provided by GRIP, Shedd was able to avoid some of the typical challenges that organizational leaders face — playing multiple roles and wearing various hats, risking feelings of isolation amid a flurry of meetings, swinging between exhaustion and exhilaration as the vision takes shape.

During this phase, Shedd harnessed his skills as a hip-hop group leader for strategic planning and building social capital. He laid the groundwork for capacity building and sustainability by earning trust from leaders, forging connections in Bible publishing and engaging in effective fundraising. And he wisely focused on community and collaboration, as he sought advocates both within and beyond GRIP.

Shedd initiated scaling efforts, taking on odd jobs with friends to contribute toward the salary for Streetlights’ second team member and leveraging his artist community ties for a digital audio Bible demo’s fundraising. This pivotal first year set Streetlights on a path toward resilience and significant growth, focused on mobilizing resources, managing finances and coordinating volunteers.

What began as a one-month commitment became a nine-year dynamic partnership between GRIP and Streetlights. Within GRIP’s abundant and creative embrace, Shedd and his co-leaders, Loren La Luz and Aaron López, transformed Streetlights into an autonomous organization. As with Acts 2:44-47, Streetlights and GRIP united under a common vision, sharing resources, celebrating collective successes and meeting their community’s needs with joy and gratitude toward God.

The partnership between Streetlights and GRIP exemplifies the power of unity, faith, generosity and a mutual commitment to enhancing capacity. It underscores how organizations can come together to create transformative outcomes.

Streetlights’ journey inspires me to broaden my organizational leadership views, sparking questions like: What resources do we have to empower others? Where can we find partnerships to build essential support systems and strengthen our capacity?

Rooted in Christian values, such an ethos of collaboration reminds us we are not meant to tackle this journey alone. Together, we grow stronger, shaping a future that transforms capacity building, where collective progress and innovation become our common goal.

It was dark when a group of volunteers arrived at Bethlehem Farm, a Catholic community in the hills of West Virginia.

As their minivans pulled into the gravel parking lot outside the farm’s main house earlier this fall, the 10 students from the University of Notre Dame were met by the farm’s full-time caretakers, who extended the customary Bethlehem Farm greeting: a “welcome home” hug.

“Those were the hardest hugs I’ve ever had in my life,” said Matthew Dunne, the only freshman in the group. “My initial reaction was, ‘What have I gotten myself into?’”

Mark Van Kirk, a junior studying computer science, was also startled.

“I felt like I was being treated like a close friend,” he said. “I don’t normally experience that with strangers.”

Eric Fitts, Bethlehem Farm’s director, said that surprising hospitality is exactly why hugs have become such a part of the central Appalachia farm’s culture.

In what ways could you offer “surprising hospitality” to your neighbors? What gesture fits the culture of your organization?

“We do that as a symbol of Christ in each person. What would we do if Jesus showed up on the property today?” he said. “It’s also a way of making ourselves vulnerable. When you open your arms, they’re not stiff out in front of you.”

Located in rural Summers County, Bethlehem Farm describes itself as an intentional Christian community based on “the Gospel cornerstones of service, simplicity, prayer, and community.” A group of caretakers lives and works together year-round, growing a lot of their own food, conserving as much water and electricity as possible, dressing modestly and largely eschewing technology.

‘Simplicity is countercultural’

The farm welcomes hundreds of volunteers each year for weeklong retreats, where visitors work alongside the caretakers and mirror their way of life. Fitts said the farm’s model of hosting volunteers is in part for practical reasons — it brings in more hands to accomplish the work. But it also allows those volunteers to see mindful, intentional living with their own eyes.

“Whether it’s community living or the idea that simplicity is countercultural — it’s not the way, but it’s a possibility,” he said.

The Notre Dame students were on a midterm break, and all were enrolled in the school’s Appalachia Seminar. On their first morning, Fitts gave them a grand tour of the property. The land once belonged to the Kirwan family, who ran a Catholic Worker farm on the site from 1983 until 2004. The Bethlehem Farm organization formed there in 2005, although the land was then owned by the Diocese of Wheeling-Charleston.

What would simplicity — or a more simple life — look like in your context?

Fitts, a Wisconsin native, discovered Nazareth Farm in north central West Virginia while in college at Loyola University Chicago. Nazareth Farm is another Catholic community that emphasizes prayer, simplicity, community and service and offers service retreats for groups around the country. He fell in love with the way of life there and continued to organize trips to Nazareth Farm after going to work for Wheeling Jesuit University. During one such trip, the idea for Bethlehem Farm was born.

Fitts and others realized there were far more groups on the waiting list for Nazareth Farm than the organization could host. In addition, they wanted a farm that emphasized sustainable practices, which was not a focus of Nazareth Farm at the time. And they believed West Virginia needed more intentional communities.

“There was a neighbor who kept saying, ‘There needs to be more Nazareth Farms,’” Fitts said.

The diocese turned over the property to Bethlehem Farm in 2019.

The farm covers 91 acres, but only a small part is developed. Just below the house is a large pasture, where five donkeys take care of the grass. There are beehives that Fitts’ wife, Colleen, tends. The farm cemetery sits on a hill just above the pasture.

A little way off is the chicken house with its 45 unusually aggressive hens. There are high tunnels (also known as hoop houses), greenhouses, and garden plots of herbs, sweet potatoes, peppers, tomatoes, onions, and just about everything else that will grow in this climate.

The two residences on the property — one for caretakers, the other for retreat guests — are as eco-friendly as possible. There are solar panels on the roofs. The large, homey cabins are heated by wood-burning stoves, and the plumbing is connected to a rainwater containment system with a capacity of nearly 50,000 gallons. But caretakers still limit themselves to two showers a week, and guests are invited to do the same. There are signs in the bathroom advising guests to flush toilets only when necessary.

In the kitchen, food scraps get composted into fertilizer. There’s not a disposable plate or cup in sight. When guests arrive, they choose coffee mugs and label them with masking tape — to use for the remainder of their stay. Although breakfasts and dinners are made fresh every day, lunches on the farm are a smorgasbord of leftovers.

“I told my dad these people would probably survive the longest in a zombie apocalypse,” Dunne, the freshman, said. “They would survive and be happy.”

Fitts said it’s all just part of the community’s attempt to live out the Gospels.

“When we say we’re living the gospel, I guess the question is — ‘How?’ I think in our culture right now, the default is you’re going to be living destructively: toward the environment, toward yourself, toward other people,” he said. “We’re looking to live creatively.”

Home repair and evening prayer

During their time on the farm, the students split into three work groups. Each day, two groups would work on construction projects with the farm’s Repairing Homes, Renewing Communities program, which provides free labor for home construction projects and allows clients to pay for materials with no-interest loans. The remaining group would serve as that day’s “home crew,” preparing meals, cleaning the residence and planning evening prayer.

What actions could you or your organization take to “live creatively”?

Two projects were underway when the college students visited. At one site, crews repaired a leaky roof by covering it with a new one made of metal. At the other, they measured, cut and installed new vinyl siding on a home.

Bethlehem Farm has other initiatives that go hand in glove with their home repair program. Its Sustainable Upgrade Fund allows families to use more durable, nontoxic and environmentally friendly materials in home projects for no additional cost. Its weatherization program helps homeowners insulate their homes to save on heating and cooling costs. And its renewable energy program gives low-income families 0% financing on solar panels. Volunteers help with all those projects except the installation of solar panels, which is done by professional contractors.

During groups’ first day at the farm, though, no one heads out to a work site. That day is spent doing some chores around the property and learning about the farm — and, more importantly, learning about Bethlehem Farm’s philosophy of service.

“So that we understand we’re not here to reach down a hand and lift up the ‘lowly poor,’” Fitts said.

While there was a renewed interest in helping poor Appalachians during the War on Poverty of the 1960s and 1970s, that assistance came with exploitation, Fitts said. The people of the region were often portrayed as uneducated, helpless and dirty, in need of outsiders to come and fix their issues. Bethlehem Farm is cautious not to perpetuate those stereotypes.

“We are coming with our poverty — the spiritual neglect in much of our culture, the poverty of ‘I’ve never pushed a wheelbarrow.’ And we come with our wealth, our strength, whatever it is we’re giving,” he said.

He emphasizes to students that the people Bethlehem Farm serves have their own poverty and challenges but also their own wealth — life experience, depth of faith, technical know-how, knowledge of local traditions.

That’s why Bethlehem Farm prefers not to use the term “clients” for the people it helps but rather “homeowners,” “partner families” or, even better, “neighbors.”

“Neighbors help neighbors. That’s a really strong trait of West Virginia,” Fitts said. “We just happen to be the neighbor who has 20 college kids come and visit.”

Are there nonmonetary ways for you to assess your community’s poverty and wealth? Your organization’s?

‘Small things’

Maria Vaquero, a junior education major, thought she would enjoy construction projects the most but wound up preferring her day on home crew duty. She packed lunches for the other crews and baked a cake for another student’s birthday.

“I’m a baker. I love to bake,” Vaquero said. “It’s a way of loving people.”

Vaquero still thinks about a quote — often attributed to Dorothy Day — that Bethlehem Farm house manager Molly Sutter lettered above the kitchen cabinets: “Everyone wants a revolution, but no one wants to do the dishes.”

“I think it talks about their simple way of lifestyle,” Vaquero said. “They might get criticism of how much of an impact they’re having — ‘What difference does it make?’ But it’s in the small things.”

That focus on “small things” comes through in Bethlehem Farm’s emphasis on prayer, which begins each day for the group.

“It wasn’t 30 hours of prayer. It was two minutes. And then it changed your perspective on the work you’re doing,” Vaquero said.

“We were on God’s time — that’s what they would tell us,” Dunne said. “We would start prayer while it was dark, and by the end of prayer, it was light. You could really feel time passing.”

The group prayed again before breakfast. They prayed before leaving the farm to head out to work sites and again when they arrived at the work sites. They prayed before lunch, before dinner and before bed.

For junior Van Kirk, the emphasis on prayer helped him stay focused on the reason they were there.

“It made our work feel like it wasn’t just work. It felt like it was very purposeful,” he said.

The farm has another way of fostering connection among volunteers — by asking them to fast from technology during their stay. Cell service isn’t great on the property anyway, but the students said they initially found the lack of screens a little difficult.

“I remember, at the beginning of the week, every time I would stand up from a couch I would pat myself and check if I had my phone,” Vaquero said.

But as the week went on, she noticed that the lack of phones changed how she and her peers interacted.

“It forced us to be with one another,” she said. “I’ve realized after the trip, in group settings where there’s nothing to do, people look at their phones and scroll mindlessly. But [at the farm] there was no moment of silence unless it was prayer time. Someone would find something to talk about.”

What “small things” matter in your organization?

Since returning to campus, Dunne has been thinking about how limiting screen time can make him more present with those around him — the way the people at Bethlehem Farm are, he said.

“They’re teaching us what it feels like to be part of a community,” Dunne said. “I could re-create that in my life.”

Gathered in a circle

Every Tuesday night, Bethlehem Farm hosts a community dinner. It’s open to anyone who wants to attend, but caretakers have a list of people they call each week to invite: neighbors they’ve helped in the past, members of the church they attend, other people from the community.

On the week that the Notre Dame students were there, about 40 people showed up. They filled every seat at the multiple dining tables, leaving a few guests to take a seat on couches and coffee tables.

The home crew worked on dinner all day, preparing sausage lasagna, butternut squash, garlic knots, gluten-free cheese rolls, Brussels sprouts, salad greens. One of the guests brought a Little Caesars Hot-N-Ready pizza, which the kids in attendance quickly devoured.

Would you consider fasting from cellphone use as a spiritual practice? What might be the obstacles and benefits?

But before dinner was served, everyone gathered in a circle in the center of the room. One by one, they introduced themselves and talked about their connection with the farm.

Among those in the circle were Catherine Wheeler and her mother, Bobbie. They had been introduced to the farm through its home repair program — crews had fixed the gutters, porch steps and shower at Bobbie’s house. She now comes to the dinners almost every week and enjoys the opportunity to socialize with people from her community. Bobbie suffers from COPD and Alzheimer’s disease, and Wheeler, as her mother’s full-time caretaker, doesn’t get many opportunities to interact with other people. She said Bobbie enjoys the meals too.

“I can mention we’re going to dinner at the farm, and she’s ready to go,” Wheeler said.

Near the end of the circle stood Maury Johnson of Summers County Residents Against the Pipeline — SCRAP, for short. He was making his first visit to the community dinner, but SCRAP has been working with Bethlehem Farm for months to protest the Mountain Valley Pipeline project. The natural gas pipeline, which will span more than 300 miles from northwestern West Virginia to southern Virginia, doesn’t directly affect Bethlehem Farm but will run through neighboring properties. And the project’s largest stream crossing is just down the road.

“Bethlehem Farm has been protectors of this river for a long time,” Johnson said. “They’re not boastful. They don’t say, ‘Look at me.’ They just do it.

“The world needs more Bethlehem Farm,” he said.

Around the circle, heads nodded in agreement. Then all present bowed their heads and prayed.

Questions to consider

- In what ways could you offer “surprising hospitality” to your neighbors? What gesture fits the culture of your organization?

- What would simplicity — or a more simple life — look like in your context?

- Bethlehem Farm takes a specific approach to living out the Gospels. What other actions could you or your organization take to “live creatively”?

- Are there nonmonetary ways for you to assess your community’s poverty and wealth? Your organization’s?

- What “small things” matter in your organization?

- Would you consider fasting from cellphone use as a spiritual practice? What might be the obstacles and benefits of such a practice?

The Rev. Laura Edgar said she’s long had the intention of holding conversations with her church’s neighbors at nearby Auburn University. But only recently has she learned the language and skills to do that, said Edgar, the associate pastor for youth, college and young adults at Auburn First Baptist Church.

The key, she said, is “to learn what the needs truly are, and not what we think the needs are.”

Edgar’s congregation is one of 16 to take part in The Vinery: Awakening Faith and Flourishing at the Intersection of Church and University. The program invites congregations close to college campuses that are ready and willing to build or expand relationships with their campus communities into a two-year process of congregational reflection, listening and discernment.

There are about 20 million college students across the United States, and about 5,000 churches located within 2 miles of a campus. We believe that in bringing these two communities together, the torn fabric of American life can begin to be rewoven by forming healthy human beings serving the common good in the likeness of Christ.

In 2021, the college ministry Mere Christianity Forum launched The Vinery to build connections between churches and universities with a grant from Lilly Endowment Inc.’s Thriving Congregations Initiative.

The Vinery does not focus primarily on college ministry programming or increasing attendance numbers of young people in Sunday worship. We do hope that these are manifestations of the inner work of the congregations. But before that work can begin, we invite congregations to practice deep listening.

Why deep listening? Deep listening, in simple terms, is intentionally hearing the needs and interests of others and taking them seriously. It involves listening to what is said and what is not said.

At our 2023 annual Vinery gathering, the Rev. Judy Peterson offered some guidelines. Deep listening is more than being present, having good body language and hearing what others are saying, she said. It entails exhibiting a generosity that invites speakers to talk to us from their hearts — and does not send them signals that we only have time for a summary.

We begin by asking participants to explore how they are listening to God, themselves, their congregations and their campuses. Then we ask how listening more intentionally might help them become better neighbors to the young adults, staff, administrators, faculty and alumni near them. Through their listening process, congregations can learn of needs they hadn’t anticipated or sense a call to people they hadn’t noticed.

As our first group of congregations finishes its first year, this emphasis on deep listening has made a remarkable difference.

The Rev. Bromleigh McCleneghan of United Church of Gainesville in Gainesville, Florida, said that people have started showing up in her office to talk over concerns about issues on campus and their sense of inadequacy in the face of overwhelming student need.

“Slowly, through deep listening, a nascent vision of what ministry alongside our university neighbors could be is beginning to emerge,” McCleneghan said.

Deep listening entails building relationships and allowing our learnings to guide strategic and ministry plans, rather than showing up with agendas preset by boards and councils.

Granted, it’s easier to plan a pizza party at the church than to commit to regularly eating in the student dining hall. It takes less effort to build a ministry program from a list of suggestions than to take time to learn what people really want.

But when congregations really listen to their collegiate neighbors, they can serve them better. One Vinery congregation heard from students that buying textbooks was a financial burden; the church created a fund to help them. In another congregation, young adults are finding companionship with a small group of octogenarians who drink tea and knit on Friday afternoons.

Deep listening doesn’t stop at listening, though; it merely starts there. The next step after hearing people’s needs is making an effort to meet those needs.

McCleneghan in Gainesville said the conversations she’s had have inspired her to take that next step.

“It’s not what I anticipated, but it certainly feels important. Deep listening is allowing me and the other lead team members to hear God calling us to some new thing,” she said.

McCleneghan said she has scheduled a meeting to talk with the folks showing up in her office and sending her texts — an event that will be “just the next stage of this unfolding conversation.”

Peterson, in her address to the annual Vinery gathering, said that a deep listening practice isn’t just for specific occasions or meetings; how we listen — or fail to listen — in the everyday, mundane moments of our lives creates our listening habits.

The Rev. Elexis Wilson, the pastor at Wayman African Methodist Episcopal Church in Bloomington, Illinois, said at the gathering that we have to discipline ourselves not to mentally multitask by thinking about what’s next or how we might fix the problem at hand: “Many times, the task is to just listen.”

For Wilson, whose father was a pastor, this practice has particular meaning.

“I do not think I am ever listened to without [listeners] looking for the end game,” she said. “As a preacher’s kid, I felt like there was no genuine want to know my thoughts unless they wanted something from my father or were being paid. Nobody naturally would sit and hear me.”

Deep listening is vital to The Vinery’s process. It requires that we be intentional about prioritizing listening, even when it’s inconvenient.

Can we teach ourselves not to answer the phone when we’re distracted? Can we avoid thinking about laundry or clicking on Facebook during Zoom meetings? Can we learn to say, “I’d like to hear what you’re saying, but now is not a good time — could we schedule a conversation later, when we both can focus?”

How do we listen, not only to our congregations, campuses and constituencies, but also to our co-laborers? How might our deep listening make us better disciples, colleagues, leaders and friends?

Yes, it feels terribly inefficient. Yet I know that for my life as a disciple — as well as for congregations — it’s crucial. May we help people know that they are cared for and listened to — by us and by God.

Deep listening doesn’t stop at listening, though; it merely starts there. The next step after hearing people’s needs is making an effort to meet those needs.

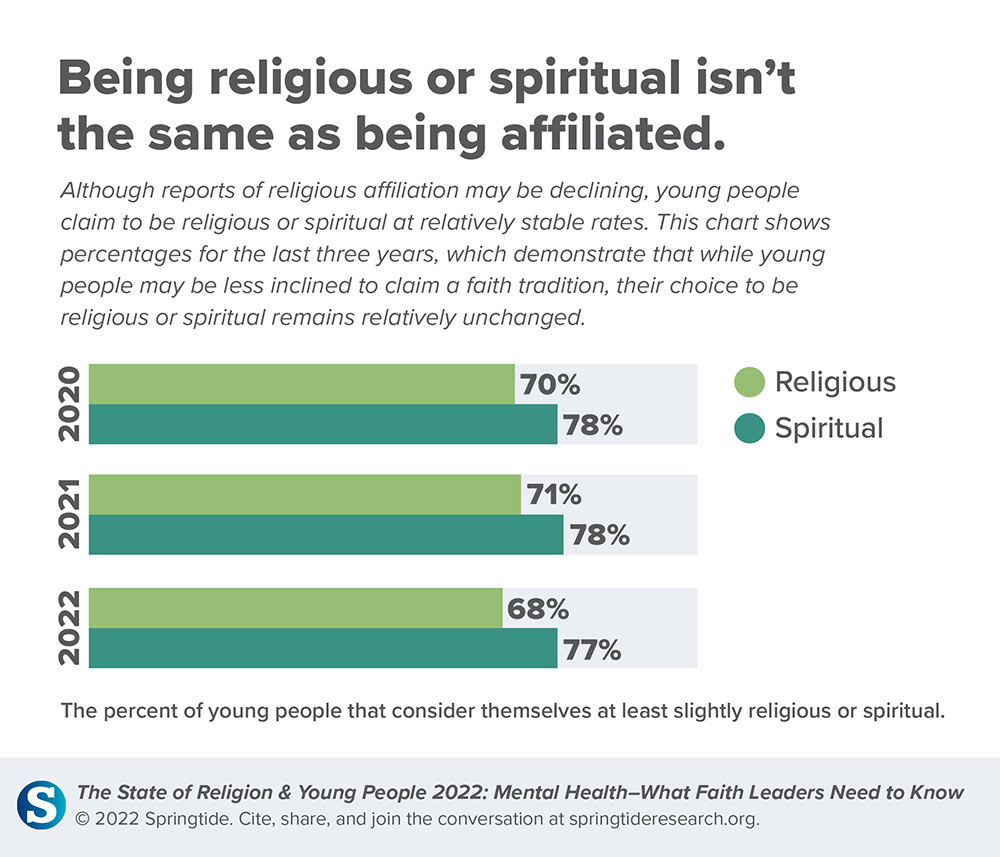

There’s more to the story about religion in America than what polls and surveys indicate — especially among young people.

Consider two recent statements made by one of America’s most prolific religious demographers, Daniel Cox. On the one hand, in a report examining Gen Z’s religious attendance and affiliation trends, he wrote: “In terms of identity, Generation Z is the least religious generation yet.”

On the other hand, in a co-written report about faith after the pandemic, this: “Increasingly, religious affiliation may tell us less about the full range of religious and spiritual experiences Americans have and the extent of their theological commitments.”

Our research findings confirm this tension: Gen Z expresses religiosity and spirituality, but in ways that defy traditional polling measures.

In this new reality, faith leaders can accept existing data as evidence of declining demand for religion among young people and just keep trying to get them back in the church building.

But we firmly believe that the decline narrative is not the full story. We think the better option for faith leaders is to transform their approach to young people in a way that recognizes how they actually are engaging with faith and spiritual practices.

At Springtide Research Institute, we are discovering that in reality, a majority of America’s “least religious generation” identifies as religious (68%) or spiritual (77%) — a fact that changed little even as their already low religious attendance dropped off further during the pandemic.

Gen Z expresses religiosity and spirituality, but in ways that defy traditional polling measures.

So what’s going on with young people?

For decades, sociologists and demographers have looked to two primary indicators of religiosity in individuals or society: affirmed beliefs (e.g., “Do you believe in God with no doubts?”) and frequency of attendance at religious services.

A recent article based on these indicators, for example, doubles down on the thesis that the U.S. is undergoing a process of secularization.

But it’s important to look more closely. This same article notes: “Of course, compared to most other wealthy countries, the U.S. is quite religious. Fifty-five percent of Americans, for example, say they pray daily, compared to an average of 22% of Europeans.”

This includes 47% of Gen Zers who pray at least weekly, according to Springtide’s 2022 annual State of Religion & Young People report.

With Gen Z, traditional indicators of affiliation and attendance no longer explain what’s happening. Cox and his co-authors call this the “decoupling of identity and experience.”

There are far too many voices pronouncing God “dead” (or at least dying) for Gen Z without the full range of evidence needed to back up such a claim.

Those indicators cannot tell you, for example, that numerous young people engage with crystals and herbs, anime, activism and politics, tarot, and nature as spiritual exercises.

Before dismissing these practices as New Age frivolities, consider that young Latter-day Saints and Muslims — groups that traditionally hold more conservative/orthodox religious beliefs — were among the most likely to engage with tarot or other forms of divination on a regular basis (38% and 35%, respectively).

Gen Zers engage in these practices even as they tag along with mainstream religious traditions. We also know that young people who engage in practices like these reap some of the benefits that accompany traditional religious behaviors and expressions.

For example, while 17% of all young people say they are flourishing in their faith, this number increases for young people who engage spiritually with crystals and herbs weekly or daily.

Similarly, while 24% of all young people say they’re flourishing in their mental and emotional health, this number increases for young people who engage with crystals or herbs weekly.

We’re not arguing that Christian churches should replace liturgy with crystals. But a deeper understanding of young adults’ faith and practices can help churches connect with them.

Some faith communities have picked up on Gen Z’s unconventional spiritual quest, dumping traditional programs in favor of eclectic, peer-driven activities that promote what Gen Z says it lacks most: a sense of belonging.

One example is Table Bread, a ministry of The Table United Methodist Church in Sacramento, California. The church discovered that the baking and breaking of bread created community for young people that helped alleviate their isolation and loneliness. As they form authentic relationships around baking bread, the participants have rich and honest conversations centered on Wesleyan concepts and questions.

The project eventually evolved into a youth-led social enterprise that is forming an intergenerational community through farming and bread making. Yet a young person’s participation in these initiatives might not register under traditional survey measures of religious identity and attendance.

And take a look at what happened in February 2023 at Asbury University, where a garden-variety chapel service ignited a two-week, continuous revival, drawing nearly 50,000 students and visitors from around the country. It also sparked similar events on other campuses.

Daniel Darling, a bestselling Christian author and pastor, wrote in response to the Asbury revival:

“I’m bullish on Gen Z. God is doing something. I’ve seen it on our own campus. I’ve seen it on campuses where I’ve preached. We need wisdom and discernment, but I don’t want to be the cranky old guy who obsesses over trend lines, nitpicks away and misses a movement of the Spirit.”

To be sure, the revival has its skeptics. However, whether one is a doubter or a believer in the Asbury revival, the event at least suggests that maybe the experts don’t have the full story on where young Americans are headed with religion. In fact, one could argue that we simply cannot know for sure right now.

Returning to the findings of researcher Daniel Cox: “What most distinguishes Generation Z from previous generations is not that Gen Zers are more likely to leave their childhood religion, but rather that many of them lacked a religious upbringing.”

Cox notes that 15% of Gen Zers report being raised in nonreligious households, more than twice the rate of Gen Xers (6%) and five times the rate of baby boomers (3%).

Many of them say they don’t know how to connect to communities of faith. Almost 40% of young people in Springtide’s 2021 annual State of Religion & Young People report agreed with the statement, “I would not even think to go to a faith community because it is not something I’ve ever gone to before.”

More than half said, “I’m not sure how to get connected to a new faith community.”

The decline of institutional trust, the increase in demographic diversity and the rise of social media, among other factors, mean that young people are operating in a different social environment than the one that gave rise to the successful program-driven models of youth engagement over the past 50 years.

What can faith leaders do in place of programs? They can invest in building trust through authentic relationships with young people rather than relying on institutional authority to do the lifting. They can promote belonging to the same degree as believing. They can address the issues that young people care about, like racial and ethnic identity and mental health. They can bake and break bread.

At Springtide, we know that there are more examples of innovative approaches to engaging young people, because young people tell us about them all the time.

With a new grant from Lilly Endowment Inc., we are excited to spend the next three years identifying the who and the what behind those approaches and why they are so successful with young people, with the goal of developing frameworks that can be adapted and applied in faith communities everywhere.

We are excited to tell a new story — perhaps even the true story — about the spiritual potential of young Americans. Among the epitaphs written about young people and the church, we hope to announce new births — and to normalize a posture of hope and anticipation for the exciting places young people will take religion in the years to come.